When Ordinary People Risked Their Lives to Fight for Freedom

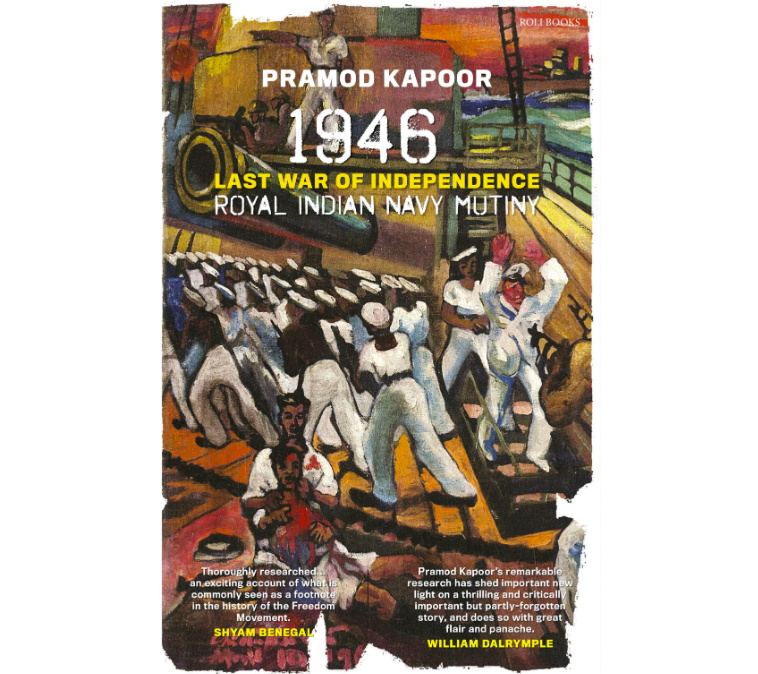

The ratings’ rebellion of February 1946 was triggered by their poor treatment in the Royal Indian Navy (RIN), but they were also inspired by the political cause of the Indian National Army leaders (INA), whose prominent members were then on trial. Civilians and servicemen across India, numerous progressive figures and the Communist Party backed the 20,000 sailors, of all religions, who took over ships and shore establishments. This revolt demonstrated to the British that people no longer accepted foreign rule over India.

The ratings’ rebellion lasted just four days. But it inspired common people, who took to the streets in solidarity. While Bombay was the epicentre and suffered the most, there was unrest in Karachi, Vizagapatam, Madras, Calcutta, Ahmedabad, Trichinopoly, Madurai, Kanpur, and elsewhere. Inspired by the RIN mutiny, people risked their lives to fight for freedom. The British struggled to control the crowds that poured out onto the streets. The protesters were undeterred by indiscriminate firing. The courage of the ratings had infected ordinary people.

In Vizagapatam, the Communist Party organized a procession of workers and other citizens carrying posters, which said ‘Release Arrested Navy Boys,’ and ‘Down with Imperialism’. The authorities retaliated with the imposition of Section 144 [of the Criminal Procedure Code] and banning all mass gatherings for one month.

In Calcutta, an unprecedented strike led by Calcutta Tramway workers resulted in complete paralysis of all forms of transport—trams, buses, taxis, and even trains. Almost one lakh students and workers took to the streets. The demonstrators carrying the flags of the Communist Party, Congress and Muslim League went around the city shouting slogans and urging the three parties to unite and help the naval ratings. They congregated at Wellington Square, where they were addressed by the leaders of all three parties.

On 24 and 25 February, Ahmedabad also saw massive demonstrations. Some 6,000 communist workers rallied at Kamdar Maidan and called for a hartal. Taking a cue from the communists, over 10,000 mill workers, mostly owing allegiance to Congress and Muslim League, struck work and eighteen mills were wholly shut.

In Trichinopoly, almost 10,000 mill and office workers took out a mile-and-a-half long procession to demonstrate solidarity with the ratings. There was a complete hartal in Madras where students, workers, shopkeepers staged another massive rally in Tilak Ghat. There were bloody clashes with the police at Elliot Road and Royapuram. In Madurai on 27 February, a day-long bandh culminated in a meeting of over 50,000 people pledging support to the naval ratings.

Karachi also witnessed widespread protests and violence. The surrender of the HMIS Hindustan after a pitched battle led to people pouring out onto the streets. On 22 February, the city came to a standstill as a public meeting held by the CPI [Communist Party of India] asked people to support the ratings. An estimated 5,000 people were in attendance. Another 30,000—Hindus and Muslims, mill workers and students—poured into the famous Idgah Maidan on 23 February in another protest march led by the CPI, which the Congress and the Muslim League noticeably avoided.

A panicky district magistrate (DM) issued Section 144, but people refused to stay at home.

By 12.30 p.m., authorities had fired tear gas shells repeatedly, but their efforts were thwarted by brave women who used buckets of water to drench the protestors and ensure the tear gas had little effect. At 2.00 p.m., young men and women started to throw stones at their oppressors, who retaliated with machine gun fire. Four protesters were killed on the spot, but the battle continued as more men ferried in from Manora Island and joined the protest. The police opened fire several times. Official figures mention eight deaths and twenty-six seriously injured. The injured were ferried to the city by public vehicles, with owners/drivers refusing payment.

Reporting the unrest in Karachi, Dawn’s front page declared: ‘Karachi Police Open Fire.’ The body text read: ‘The Police opened fire in Karachi on Friday (22 February) on a crowd near Idgah Maidan that advanced on the police three times at about 2.30 p.m…. Three Communist leaders were arrested on Saturday morning, who were addressing a meeting calling upon the public to observe hartal. Later six school boys and milk vendors were arrested…for attempting to take possession of the municipal office…and for stoning the police.’

The spontaneous and widespread demonstrations, by common civilians, including women and children, was yet another factor that accelerated the British decision to quit India. They could no longer rely on their overwhelming advantage in weaponry to cow the common people, and there had been multiple incidents where Indian policemen and soldiers refused to shoot at their countrymen.

---

History would record the naval uprising of February 1946 as the beginning of the end for the British Raj. The epic struggle for freedom would finally bear fruit eighteen months later, and undoubtedly, the heroic efforts of the ratings made a significant contribution. For four days and nights, the ratings took on the military might of the British, and they almost succeeded. They had nearly pulled off the incredible feat of taking over the Royal Indian Navy and delivering it to the national political leaders. They might well have succeeded but for the lack of support from the political leadership.

The death toll, primarily recorded in the street battles across Bombay, was already among the highest ever recorded at that time. The street clashes would continue with citizens battling the police for several more days. For the ratings, the surrender was a poignant, heart-breaking moment. The failed uprising and the punishment subsequently meted out to the ringleaders and others was even more heart-rending.

Within forty-eight hours, the authorities had launched mass arrests picking up every rating who had taken part in the uprising. [MS] Khan [a leader of the mutiny], Madan Singh [elected vice president of the Naval Central Strike Committee or NCSC], and other key members of the NCSC were taken into custody and transported to detention camps.

---

While no official figures have ever been released, [Balai Chand] Dutt [“an irrepressible man with strong communist leanings” who “believed more in Netaji Subhas Bose than Mahatma Gandhi” and wrote a book on the episode] estimates that over 2,000 ratings may have been rounded up across various centres in mass arrests. They disappeared from the pages of history. This is a fairly credible assessment since roughly 400 ratings were arrested in Bombay alone during the first wave of detentions, and at least another 500 were held in Karachi.

The arrests were certainly sweeping. Within ten hours of the surrender, 396 ratings were arrested in Bombay. Of them, about 80 were from the shore establishments, like Talwar, Castle Barracks, Fort Barracks and another 180 ratings from ships in the stream, and about 130 more from the wireless station in Mahul and the smaller ships in the Bombay docks. Khan’s subsequent ordeal would be painful…. Khan and Singh both knew very well the British would show them no mercy, and they were in the first batch of 396 ratings who were moved in secrecy to the Mulund camp, located in the northeast of Bombay.

High barbed-wire fences greeted them every morning, and there was no news of fellow ratings or the outside world. The British wanted to break these men and snuff out any possibility of future resistance. At the Mulund camp, caged on all sides by barbed wire, they were herded into groups and housed in the most inhuman conditions in Nissen huts. They were beaten and kicked and even denied food, water, and medicines. Many broke down and had to be hospitalized, with guards keeping a watch on these men as they lay emaciated and unconscious on unsanitary bug-infested beds.

Those of their colleagues who had been lucky enough not to have been arrested kept up a semblance of resistance by smuggling nationalist papers past sympathetic Mahratta guards. These newspapers carried stories of their valour, which helped to keep their spirits and morale high. They still hoped that nationalist political leaders, who had promised to protect them against victimization, would come to their aid. But this hope turned out to be naive.

The subsequent fates of many of these brave young men remain unknown. They did time in jail or detention camps; they were then dishonourably discharged. Many disappeared and have never been found or traced to date, and their stories remain lost to us. This is a gap in the historical record, which is simply unforgivable.

Pramod Kapoor, 1946: Last War of Independence, Royal Indian Navy Mutiny, Roli Books, 2022

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.