Why J&K’s Demography Will Change Beyond Belief

In the 1990s, Jammu and Kashmir intensely speculated the possibility that the Union government might want to alter its demography to deny militants their support base among Muslims, who constituted 68% of its population then. This speculation perhaps arose because the Union government legitimately insisted, on the basis of the Indian Constitution, that J&K was an integral part of India.

The speculators thought the Union government had two options. The obvious of these was to abrogate Article 35A of the Indian Constitution, which recognised J&K’s right to define permanent state subjects, who alone could enter state services and educational institutes, enjoy property rights, and vote in the Assembly elections. These rights ensured that outsiders did not swamp the state and dilute its identity.

In those years, it was hard to imagine the Indian state reading down Article 370 and abrogating Art 35A (which the Narendra Modi-led National Democratic Alliance government did on 5 August 2019). Might it not opt for the second option of issuing permanent resident certificates to non-state-citizens, eventually diluting J&K’s particularistic or special identity over time?

Soon, the speculation turned into a popular allegation. It triggered an outcry that prompted Chief Minister Farooq Abdullah to institute, in 1999, the State Subject Inquiry Commission under Justice (retd) AQ Parray. The commission was tasked with probing whether permanent resident certificates had been issued to those who did not qualify for it. In local parlance, such certificates are called fake PRCs, or fake permanent resident certificates.

The Commission, in 2013, identified 137 PRCs and recommended their cancellation. Its recommendation came to Basharat Bukhari, the revenue minister in the Peoples Democratic Party-Bharatiya Janata Party government, in 2016. He endorsed the recommendation, suggested amendments in law to severely punish those who issue fake PRCs, and forwarded his proposals to the Cabinet, which approved it. The file went to Chief Minister Mehbooba Mufti. And that was where matter came to rest.

It would seem 137 fake PRCs are just too few to bother about. The commission was, however, empowered to only probe complaints made against people possessing fake PRCs. It could not conduct a suo motu inquiry. “This is why the Commission’s list [of fake PRCs] cannot be treated as an exhaustive one,” Bukhari, who is now in the National Conference, said to us. Only a comprehensive examination of all PRCs could have provided a realistic picture of the number of fakes floating around.

This backstory assumes significance in the wake of the J&K government notifying on 18 May, the Jammu and Kashmir Grant of Domicile Certificate (Procedure) Rules, 2020. These rules prescribe qualifications required for different categories of people to apply for domicile certificates, and the documents they will need to furnish in support of their claims.

The PRC is one among the many documents that can be submitted to secure the domicile certificate. Thereafter, the importance of the PRC will be extinguished: its holder will no longer enjoy special rights. All those who possess domicile certificates will have the same rights too.

The government could have treated the PRC on par with the domicile certificate. It did not, because the PRC was textual evidence, so to speak, of the uniqueness of Kashmiri identity. Khurram Parvez, programme coordinator, J&K Coalition of Civil Society, said to us, “At one stroke, the PRC has become a subordinate certificate.” This symbolically represents the attempt to textually bury J&K’s particularistic or special identity. India had promised to preserve Kashmir’s identity within what is now popularly called the idea of India.

Before its burial, the authorities will have little time to separate the genuine PRC from the fake PRC, which too will be submitted to acquire domiciliary status. This is just one example of the many ambiguities inherent in the Domicile Certificate Rules. One of the two authors reached out to Rohit Kansal, principal secretary, Information Department, for clarifications regarding the Domicile Rules. Kansal asked him to WhatsApp the queries, which was accordingly done. We waited for 48 hours before writing about the possible extent to which J&K’s demography can change because of the Domicile Rules.

The 15-year rule:

Section 3(a) of the Domicile Rules states that any person who has resided in J&K for a “period of 15 years” will be eligible for the domicile certificate. This category will include all those who have PRCs, whether genuine or fake, refugees from West Pakistan who settled in J&K at the time of Partition, and outstate migrants who have been in Kashmir for 15 years or more. The phrase “period of 15 years” suggests he or she should have continuously resided in J&K for those many years. There are Census data available on outstate migrants. The data can be mined to quantify the number of people who will stand to benefit from Domicile Rules.

Outstate migrants:

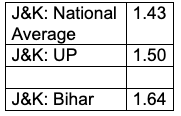

J&K counts among the exceptions in north India that attracts migrants from other states, largely because of its relatively higher wages. Its wages are 1.43 times higher than the national average wage, 1.5 times more than Uttar Pradesh’s, and 1.64 times more than Bihar’s (See Table I).

Table I: Ratio of Wages of Jammu and Kashmir vis-à-vis National Average, Uttar Pradesh (UP) and Bihar

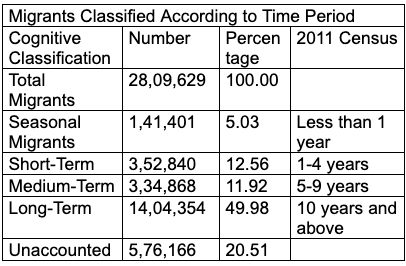

Parsing the 2011 Census report on migrants, we found that migrants constituted 28.09 lakh of J&K’s population of 1.23 crores. (Of the 1.25 crore, Ladakh, which was carved out of J&K last year, accounted for just 2.90 lakh). Once there, outstate migrants seem inclined to settle down in J&K, not least because its free, high quality school education enhances the life-chances of their children. Table II displays migrants according to the number of years they have lived in J&K.

Table II: Breakup of Migrants in Jammu and Kashmir (2011 Census)

From Table II, it is clear that by 2011, nearly 50% of migrants, or 14 lakh, had already been living in J&K for 10 years or longer. Around 12%, or 3.35 lakh, have been there for between five and nine years. Ten years have passed since the 2011 Census, and drawing from available population data, we estimate that 17.4 lakh people can certainly acquire domicile rights, which constituted roughly 14% of J&K’s population of 1.23 crore in 2011.

This figure cannot be scoffed at. It will alter J&K’s political topography. Unlike previously, they will now get to vote in the J&K’s Assembly and local elections. With victory margins consistently coming down, migrants-turned-domiciles will acquire an incredible political heft.

But the 17.4 lakh figure will likely balloon, as even a percentage of short-term migrants, by 2020, will have lived in J&K for 15 years. Add to this the possibility that a slice of the “unaccounted” migrants, or those who did not, in 2011, reveal the number of years they had been living in J&K, could have been also there for 15 years and more.

This alters the nature of J&K demography, and reduces the political significance of those who were permanent state subjects. It is a truism that a region’s political and socio-cultural identities are inextricably woven together.

The seven-year rule:

Section 3(a) of the Domicile Certificate Rules states that a person who has studied for seven years and passed Class X or Class XII in the Union Territory of J&K can apply for the domicile certificate.

Children, unless admitted to a residential school or to government-run hostels, are very unlikely to have lived alone for their schooling in J&K. Who would they be? They would be children of outstate migrants, whether holding menial jobs, or working in the private sector, or running their businesses. Their parents might not meet the 15-year rule, but their children would in case they have studied in J&K for seven years and passed Class X or Class XII. Woe betide those who have failed! They cannot become a J&K domicile.

It is possible a private sector executive, after working for seven or eight years in J&K, can get transferred out of the Union Territory. But his or her children can still return to J&K in the future, to acquire the domicile certificate.

Anuradha Bhasin, executive editor of the Kashmir Times, points to another anomaly: “The Domicile Rules do not have a cut-off period. Presumably, anyone who has studies for seven years over the last 70 years qualifies for the domicile certificate.”

Add all the beneficiaries to the 17.4 lakhs of outstate migrants who meet the 15-year rule and you can grasp the nature of demographic change being attempted in J&K.

The Pakistani refugee:

Under the 15-year rule will also come the families which fled West Pakistan to J&K and settled there. There are varying estimates regarding the number of West Pakistani refugees in J&K, from 2.5 lakh to 5 lakh. Their non-state resident status was cited as a significant reason for justifying the abrogation of Art 35A. The refugee issue, however, took an unexpected turn in 2018.

In that year, the central government decided to provide Rs 5.5 lakh to each of the West Pakistan refugee families as one-time financial assistance. According to an Indian Express report, not a single family applied to avail of the assistance. Some who did subsequently withdrew their applications.

The newspaper quoted sources in the bureaucracy and among refugee leaders to explain the phenomenon of zero application. Most refugees either did not carry documents at the time they fled West Pakistan to establish their place of residence or they misplaced these over subsequent decades. Or they all had procured PRCs over time, through fraudulent methods. Apprehensive that they could be booked for acquiring fake PRCs, they chose to forego the Rs 5.5 lakh, not a paltry amount.

Ideally, the event of 2018 should have prompted a neutral administration to probe why not a single West Pakistan refugee stepped forward to claim the financial assistance. The history of misdeeds inherent in securing fake PRCs will be forgotten as the domicile certificate supersedes the PRC now.

The Indian Express quoted refugee leaders saying that there are around 20,000 West Pakistani refugees in J&K. What then is the basis to claim that anywhere between 2.5 and 5 lakh refugees reside in J&K? What purpose does it serve?

Intrastate migrants:

Section 3(b) of Domicile Certificate Rules offers domicile rights to all migrants who are registered with the Relief and Rehabilitation Commissioner (Migrants) in J&K. These are, essentially, migrants who shifted out of Kashmir to Jammu because of militancy.

Around 1.53 lakh Kashmiri migrants, spread over 43,930 families, are registered with the Relief and Rehabilitation Commissioner. Also registered with the Commissioner are another 979 families that migrated from different parts of Jammu region, such as Doda, Udhampur, Rajouri and Poonch, to areas relatively free of militancy.

All these families, native to J&K, should be having PRCs. This has Bhasin raise a pertinent question: “Since they all should be having PRCs, why have they created a separate category for [internal] migrants. Officials say that Kashmiri Pandits, who were earlier not registered [with the Relief and Rehabilitation Commissioner], will now be allowed to register.”

Assuming this to be the case, even these Kashmiri Pandits would be having their PRC, or that of their parents. Bhasin, therefore, asks, “Are they trying to get back Pandits who left for other parts of India, say, a century or more ago?” A rolling back of the clock will swell up the number of non-Muslim Kashmiris and enhance their power.

Elite accommodation:

Perhaps the most contentious of all sections of Domicile Rules is 3 (c), which says that children of “Central Government Official[s], All India Service Officers,” and of others in a slew of Central government institutions who have served in J&K for a “total period of 10 years” are eligible to apply for domicile certificates.

There is no cut-off period prescribed, thereby implying that children of all those who have served in J&K can apply for the domicile certificate, subject to them having served for a total of 10 years.

A question arises: does the number of years served by a central government official or an Army soldier should cumulatively add up to 10 years? The confusion over the meaning of a “total period of 10 years” is best illustrated by an example. An official or an officer could have served for four or five years in J&K before he or she was transferred out. A few years later, he or she returned to J&K to serve for another five or six years. Altogether, he or she will have served for a total of 10 years. Will this method of counting apply? Or will officers need to serve 10 years on the trot? We asked this to Rohit Kansal, who did not respond.

It does, however, seem the framers of rules mean “total” in the cumulative sense, more so as the phrase in section 3(a) says a “period of 15 years,” suggesting a continuous residence of 15 years. It also seems the domicile right is offered to the children of officials, who themselves do not qualify for it, a clear example of gross absurdity.

We could not secure data to count the number of central government officials and officers who have, over the last seven decades, cumulatively done 10 years of duty in J&K. Parvez said, “The numbers will be huge. It is very clear that the door to J&K has been thrown wide open for outsiders to acquire domicile rights, buy property there or enter the state services.”

The incentives:

Obviously, the children mentioned in section 3(a) or 3(c) will not come to J&K unless they are abject failures wherever they reside, or have upward mobility as their principal motivation. For them, the changes brought about in J&K’s legal architecture offer incentives. They only need to be adventurous to milk them.

Until 5 August 2019, no person outside of J&K could purchase land there. But now, the government has removed all legal obstacles to outsiders purchasing land in J&K. Thus, section 139 and section 140 of the J&K Transfer of Property Act, 1977, section 20-A of the J&K Big Landed Estates Abolition Act, 1950, and section 4 of the J&K Alienation of Land Act, 1938, have all been abolished. These provisions prohibited sale and transfer of land to outsiders.

Former Law Secretary Ashraf Mir said, “These changes are an invitation to outsiders to acquire property in J&K.” Needless to say, in another 15 years, they can also opt to become J&K domiciles. Since power chases wealth, they can hope to even enter the J&K Assembly.

The tinkering of laws also provides incentives for the lower classes. Take the J&K Property Rights to Slum Dwellers Act, 2012, from which all reference to “permanent resident of the State” has been omitted, including in section 3. In effect, section 3 now reads, “Notwithstanding anything contained in any law for the time being in force, every landless person who lives in a slum area in any city or urban area as on 01-01-2010 shall be entitled to a dwelling house at an affordable cost.”

This should entice the Hindi heartland’s lower class, which can access J&K’s quality education free of cost and get a cheap accommodation to boot. The ownership of a dwelling house will generate a property document, which can be submitted to acquire the domicile certificate. A large number of outstate migrants can, therefore, become domiciles by 2025.

Parvez thinks the change in the Slum Dwellers Act is Delhi’s master-stroke. He explains, “The urban Indian middle class person is not particularly interested in settling down in J&K, where the opportunities are far limited in comparison to other parts of India. He or she will prefer to go abroad. By contrast, it is a lucrative offer to the lower class from the Hindi heartland.”

Parvez also feels land and houses will be bought in Jammu region, at least in those districts having Hindu majority. “In the Valley,” Parvez said, “there will be immense social pressure not to sell land to outsiders. This form of pressure will also come from militants.” Parvez also pointed out that Pakistanis are legally proscribed from buying land in the part of Kashmir that is under their control.

For sure, Jammu region’s landscape will stand altered, along with its demography. Bhasin predicts, “A floodgate may have been opened for land-sharks, realtors and big companies. Its impact on the environment could be severe.”

Former Cabinet minister and Congress leader Raman Bhalla railed against section 3(c), arguing that the backdoor inclusion of outsiders as domiciles will make it difficult for natives of J&K to secure jobs and seats in educational institutes. “There is disquiet,” Bhalla said. “That is the reason why the BJP is so reluctant to hold the Assembly elections.”

NRIC versus domicile certificate:

The Domicile Certificate Rules are designed to include as many non-permanent residents in the category of domiciles as possible. This is evident from the reading of section 5 and section 6. Thus, section 5 names the “competent authority” to which documents have to be submitted by each category of applicants in support of their claims to domicile certificates. In most cases, it is the Tehsildar who is the competent authority.

Section 6 states that the competent authority must accept or reject the application for a domicile certificate within 15 days. In case he or she does not at the expiry of 15 days, the applicant can appeal to the appellate authority, which in most cases is the Deputy Commissioner. Should the appellate authority uphold the applicant’s appeal, the competent authority, or the Tehsildar, must issue the certificate in the next seven days, failing which a fine of Rs 50,000 will be imposed on him or her.

Given the phenomenon of fake PRCs, and the ease with which ration cards, rental documents, etc. are dubiously generated in India, the Tehsildar will be under pressure to ignore his own misgivings regarding the supporting documents. After all, those who receive their certificates will not go in appeal to the Appellate Authority.

Clearly, the Domicile Certificates Rules emphasises upon the principle of inclusion. In other words, the Rules give the benefit of the doubt to the applicant.

Contrast this with the procedure prescribed for preparing the National Register of Indian Citizens. Under it, anybody can object, at different stages, to the inclusion of a person in the National Register of Citizens. The onus lies on the suspect to prove his or her bona fide. The emphasis here is on the principle of exclusion.

Is it wrong to conclude that the procedure for the NRIC has been made stringent for weeding out Muslims and marginalised groups, as have been explained by legal experts? Likewise, it is wrong to conclude that the lax procedure for granting domicile certificates in J&K is designed to include as many outsiders, preferably Hindu, in the category of domiciles?

Regardless of the answers to these questions, one thing is certain—J&K’s demography is bound to get altered beyond belief, at a speed so astonishing that the procedure for issuing domicile certificate would seem, quite unfortunately, a quasi-colonial project.

Ajaz Ashraf is an independent journalist and Vignesh Karthik KR is a PhD student at King’s India Institute, King’s College London.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.