Women of Shaheen Bagh: Defending Constitution and Democracy

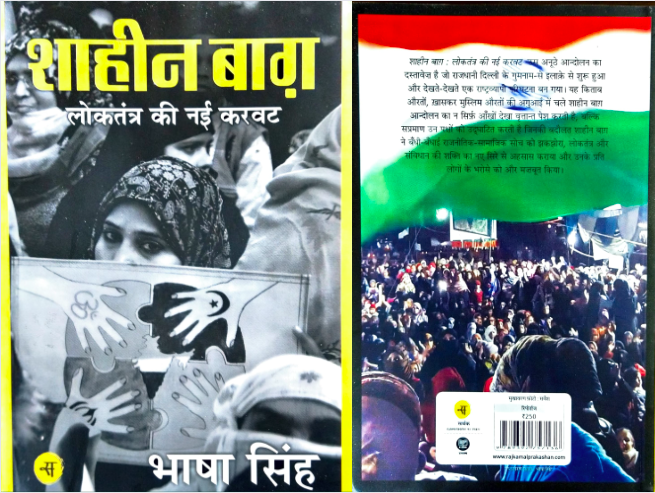

Shaheen Bagh: Loktantra ki Nayee Karvat (Shaheen Bagh: A new turn of Democracy) is a book written by senior journalist Bhasha Singh and published this year by Sarthak – an imprint of Rajkamal Publications. The book records one of the most significant movements of the first quarter of the 21st century. It is about the people’s protest that started from Shaheen Bagh in Delhi on December 15, 2019, and then spread to all across the country with about 3,000 different protest sites within 100 days – after the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 (CAA) was passed in Parliament on December 11, 2019. The Shaheen Bagh protest lasted for 101 days and ended on March 24, 2020.

The controversial act states, “Provided that any person belonging to Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist, Jain, Parsi or Christian community from Afghanistan, Bangladesh or Pakistan, who entered into India on or before the 31st day of December, 2014 … … shall not be treated as illegal migrant for the purposes of this Act…”

This essentially meant that if Muslims are not able to produce the desired documents, then they will be treated as illegal migrants, lose their citizenship, and will have to live their remaining life in detention centres. Such a grave threat compelled them to take to the streets to register their dissent and they started protesting at Shaheen Bagh very peacefully, creatively, sensibly, and maturely.

First of all, the protesters maintained peace at their protest sites, and if miscreants tried to infuriate the people, the protesters handled it with maturity. Poems, songs, slogans written and sung in support of Shaheen Bagh, and the kind of installations (a detention centre, India Gate, and an Indian map) and a library made at the protest site were useful in educating people about the CAA and the importance of their protest in a direct manner. All these characteristics have been captured in Singh’s book. It emphasizes the sensibilities of the leadership and the secular structure of the movement while tracing its connection with Indian Constitution and the thoughts of Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar.

The leadership of the movement remained in the hands of Muslim women and women of all ages participated in the movement – from students to working women, and from homemakers to grandmothers. Dadis and Nanis (grandmothers) and other Muslim women sitting at the protest site of Shaheen Bagh in the initial days narrated that how the barbaric lathi-charge at Jamia Millia Islamia and the threat of losing their citizenship shook them to the core. They now felt that they had to do something to protect their children and their citizenship. Eighty-two-year-old Bilkis, protesting at Shaheen Bagh, said: “I want to make sure that our children and their children are considered Indian; no one should question their citizenship.” The women further said if their children had not been beaten up, they would not be sitting at the protest site.

Women in this movement cannot be only seen to have been engaged in a personal battle for the protection of their children, their lives and their citizenship. They were clearly fighting a political battle – safeguarding the Indian Constitution in the defence of democracy. The grandmothers of the Shaheen Bagh were aware of this political nature, as they said, “We have come out to save our country.” If it was suggested to them that their protest might be futile and they might die for nothing, they would say, “… Come on, I will die while trying to keep the country free now even if I did not die in the fight for independence from the British. This country is my own country, isn't it?” Singh captures this act of challenging the power by the women of Shaheen Bagh in her book really well. Reading this book makes it seem like these grandmothers already knew the language of rights and democracy.

Bhasha Singh notes that though the question of citizenship of Muslims was at stake primarily in the anti-CAA movement, providing citizenship based on religion is anyway against the secular structure and Constitution of the country. She opines that the CAA was like a blueprint being prepared for revamping the secular structure of the whole country. The protesters, however, asserted the secular character by using symbols and language in tandem with this character. They hoisted the Indian national flag everywhere and displayed posters of leaders like Dr Ambedkar, Gandhi, Nehru and other freedom fighters at the protest sites. They recited patriotic songs like Vande Mataram or the national anthem Jana Gana Mana. They carried copies of the Constitution or the Preamble rather than religious books. They didn’t say that their religion was in danger, but they were talking and worrying about the nation, and their slogans were also framed to convey this message:

संविधान बचाने निकलें हैं, आओ हमारे साथ चलो

मुल्क बचाने निकलें हैं, आओ हमारे साथ चलो

हाथों में तुम हाथ चलों, आओ हमारे साथ चलो

(We are on a mission to save the Constitution, come walk on with us

We are on a mission to save the nation, come walk on with us

Walk hand in hand with us, come walk on with us)

The mobilisation at Shaheen Bagh had a clear direction because the protesters knew that the CAA and NRC are attacks on the Constitution in the first place, to be used later to revoke their citizenship. They understood that the real remedy to the issue was saving the Constitution. Singh notes that they could find a true friend in Dr. Ambedkar. Syeda Hameed, a former member of the Planning Commission, said "Ambedkar and the Constitution were the two main pillars on which Shaheen Bagh stood." The protesters said, “Ambedkar come back, we need you” and that “‘We the People of India’ are very soothing and comfortable words”. (pg. 161). They were seeing in him their saviour. Seventy-five years old Sarvari at Shaheen Bagh told Singh: “We have learned a lot. We have read the Constitution. Don't laugh, I can't read, so I asked others. They read it to me and now I know what we are doing is right as per the Constitution. That's why the photo of the person who wrote the Constitution - Ambedkar - was hung here first. He was a wonderful person too. If we would have not come to the protest, we would not have known all this.” If not for this conscious political stance, the protesters could have been quite easily attacked and their voices would have been silenced. Women’s leadership also turned out to be a difficult one to suppress. The women at Shaheen Bagh explained, “When men raise their voices, the police take them away and throw them behind the bars. That is why now we women have taken the fight to save the constitution into our own hands.”

The interesting part about the book is that Singh has not just observed and recorded women sitting at the protest sites, but also looked at how these women were managing their homes while they kept coming to the site for over a hundred days. They told Singh that the responsibilities of maintaining the home and taking care of children – which had always remained with the women until then – were being shared by men during this period. The relationship between the women and their homes also changed during the movement. The relationships between husbands and wives, between brothers and sisters, between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law, among sisters-in-law, and between mothers and daughters changed from power/hierarchical relationships to associative and collaborative relationships. Instead of dominating, they all were taking care of each other. Singh observed that power dynamics were altered and patriarchy started weakening in homes of these women. With such changes, the movement was democratising the atmosphere in different spheres. The protest presented a new picture of Muslim women who are politically vocal, self-dependent, and concerned about the country, contrary to the negative imagery used by media that would make them look weak and docile.

This protest and Singh’s book have given us a message that the more the poor, marginalised, oppressed women and religious minorities identify with Dr Ambedkar, the more the people, Indian constitution and the democracy in the country will remain protected.

The strength of the book is the first-hand narratives of the women protesters of different ages – from as young as 15 years old school-going girls to 100-year-old women. Their understanding of the Citizenship Amendment Act as anti-citizen, and the meaning of the protest they were building as a work of nation-building have made it possible to understand the power and force they wield. The way these women identified Indian Constitution as their saviour, read its preamble, and understood its chief architect, Dr Ambedkar, as the greatest symbol of nationalism and democracy, presented a promise to protect the democracy in this country.

The message they sent out sums up the importance of their role in the country:

“परेशानी के लिए माफ़ी। औरतें काम पर हैं। हम एक नए राष्ट्र को जन्म दे रही हैं। कृपया सहयोग बनाए रखें।” (Sorry for the trouble. Women are at work. We are giving birth to a new nation. Please keep supporting.)

The author is a researcher with the Safai Karmachari Andolan; the views expressed are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.