After SC Order on CAA, Only Boycott of NPR Can Nix NRIC

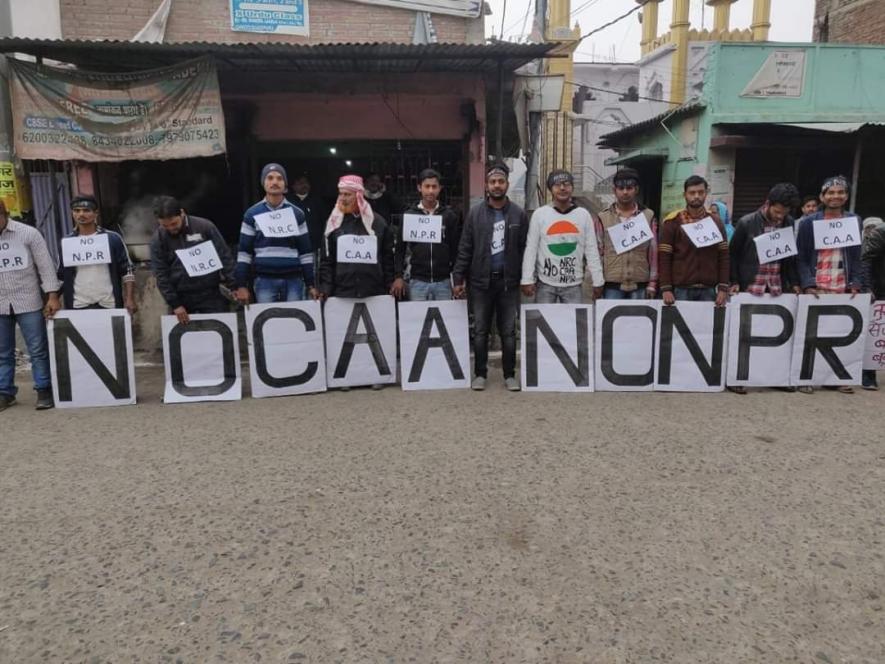

Protesters hold placard in Bihar

The Supreme Court’s refusal to stay the Citizenship Amendment Act should prompt civil society leaders to urgently focus on their plan to organise a boycott of the exercise for compiling the National Population Register, which constitutes the basis for preparing the National Register of Indian Citizens.

Not only are the exercises for preparing the two registers linked, a call to boycott the NPR is likely to elicit a greater popular response than it would at the NRIC stage. This is because the punishment for withholding or supplying wrong information for the NPR is far less than what it is likely to be for doing the same for the NRIC.

The Supreme Court has given the central government four weeks to reply to all CAA-related pleas. This will kick in a long-drawn-out court battle over the contentious citizenship issue. Until the Supreme Court delivers its verdict on the constitutionality of the CAA, the Bharatiya Janata Party can continue to depict the CAA as a protective shield for those Hindus who do not have documents to prove their citizenship.

The proposition that the CAA will protect all Hindus is a myth, as this story shows. Yet the myth sounds convincing enough to persuade the public to participate, without any fear, in the preparation of the NPR and, therefore, also the NRIC.

Indeed, the triad of the CAA-NPR-NRIC has been designed to keep the sting for the end. Of all the three instruments, the NRIC is arguably the most devastating, as those excluded from it will be deemed illegal immigrants, liable to lose their rights, including that of voting, and face the grim prospect of detention and deportation.

The NPR and the NRIC are weaved together by the Citizenship (Registration of Citizens and Issue of National Identity Cards) Rules, 2003, which have been framed by the government under the powers conferred by Section 18 of the Citizenship Act, 1955.

The Citizenship Rules, 2003 mandate the preparation and updating of the NPR, which is supposed to collect, as of now, 31 data points for every individual. Those rules also say that the data collected for the NPR will be used for compiling the NRIC. Essentially, the local registrar, whether at the ward or village level, will mark out people whose citizenship is in doubt. They will have multiple appeals to prove their bona fides, but once they exhaust all opportunities their names would be excluded from the NRIC.

The NPR is, therefore, a prelude to the NRIC or, to put it in another way, the NRIC is a subset of the NPR. The surest way of ensuring that the NRIC is not prepared is to boycott the NPR, which is scheduled to take place between 1 April and 30 September.

The boycott, however, will come at a price.

The Citizenship Rules, 2003 (section 17) imposes a maximum fine of Rs 1,000 in case a person violates any of six of its sections. One of these (section 7) states that “it shall be the responsibility of the head of every family, during the period specified for preparation of the Population Register, to give the correct details of name and number of members and other particulars” as asked for.

The NPR-related fine of Rs 1,000 is indeed a princely sum for the poor. Yet, given the community efforts witnessed in organising round-the-clock sit-ins countrywide, it will be easier to organise a public fund to bail out those who wish to join the boycott of the NPR, but cannot afford the fine.

The provision of making the household head responsible for supplying information is a tricky one. Unlike the young, who have been spearheading the protests against the CAA-NPR-NRIC, the household head may not be inclined to boycotting the NPR. Civil society activists cannot hope to make the boycott of the NPR successful without the robust participation of the elderly.

Barring section 7, the violation of all other sections in the Citizenship Rules, 2003 pertains to the NRIC. For instance, section 8 of the Citizenship Rules, 2003 states that a person is bound to comply with any order asking him or her to furnish information required for determining his or her citizenship status. The violation of section 8, too, will incur the maximum fine of only Rs 1,000.

However, the South Asia Human Rights Documentation Centre’s draft note on the CAA-NPR-NRIC contemplates the possibility of the government invoking section 18 of the Citizenship Act, 1955. This section imposes a fine of Rs 50,000, or imprisonment of five years, or both, for “false representations of material particulars” regarding citizenship status.

It is a matter of debate and interpretation whether false representations will also include the NPR data used for preparing the NRIC once the latter is initialised. According to section 6 of the Citizenship Rules, 2003, it is mandatory for every person to register with the Local Registrar of Citizen Registration during the period of initialisation of the NRIC.

Civil society activists also feel that once the government succeeds in preparing the NPR that covers over, say, 80-90% of the population, it will change the rules at the NPR stage to provide for far more stringent provisions than just a fine of Rs 1,000. A hefty fine or imprisonment will ensure a very high degree of compliance with the NRIC, which will have a severe impact on a segment of the population that does not possess documents to establish citizenship.

The debate over the process of determining the citizenship status has been confused because of the CAA, which will provide a protective shield to those among the people excluded from the NRIC who claim and can prove (the rules for providing proof have not been formulated yet) that they fled Bangladesh, Pakistan and Afghanistan because of religious persecution. Their citizenship will be fast-tracked; they will neither be detained nor deported.

The Modi government enacted the CAA to mollify the Bengali Hindus who were both perturbed and enraged at having been left out of the NRC in Assam. The CAA, however, applies to the entire country.

By enacting the CAA before undertaking the interlinked NPR-NRIC processes, the BJP has created the erroneous perception that the Hindus do not have to fear the NRIC. As explained earlier, this is a myth. Yet this perception will remain at least until the Supreme Court delivers its judgement on the CAA. The Supreme Court’s decision not to stay the CAA, in addition to granting one month to the Centre to file its reply, means the verdict will not come before the NPR exercise begins on 1 April. It could even come after 30 September, when the NPR process is scheduled to end.

The CAA has been calibrated to muster the support of Hindus for the BJP’s exclusionary idea of citizenship, and ensure that the NPR elicits the support of the largest number of people. The more people participate in the NPR, the more credibility the NRIC will have.

Conversely, an NPR that does not cover a large percentage of the population will mean an NRIC with as many Indians missing from it, thus reducing to meaningless the state’s exercise of determining citizenship. This is precisely why the Kerala government has chosen to inform the Registrar General and Census Commissioner that it will not implement the NPR. Whether or not other states follow, only a popular boycott of the NPR can nix the NRIC.

The author is a freelance journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.