Great Indian Bustard: Is it ‘Tilting at Windmills’?

Egg at Jodhpur ZOO. Picture Credit: Harsh Vardhan.

When Cervantes had Don Quixote “tilting at windmills,” in the 17th century classic, he had not imagined that the “hulking giants” could actually kill. For the large Great Indian Bustard of the Rajasthan desert, the windmill – or the large wind turbine -- is no imaginary enemy. Birds meet a bloody end trying to negotiate the high-tension wires and wind turbines in this region.

In a census in 2017-18 of the entire range of the Great Indian Bustard, it was estimated that there were about 129 birds left, with an error range of plus or minus 19. Scientists attempting to conserve this species worry that wind energy could sound the death knell for this large bird.

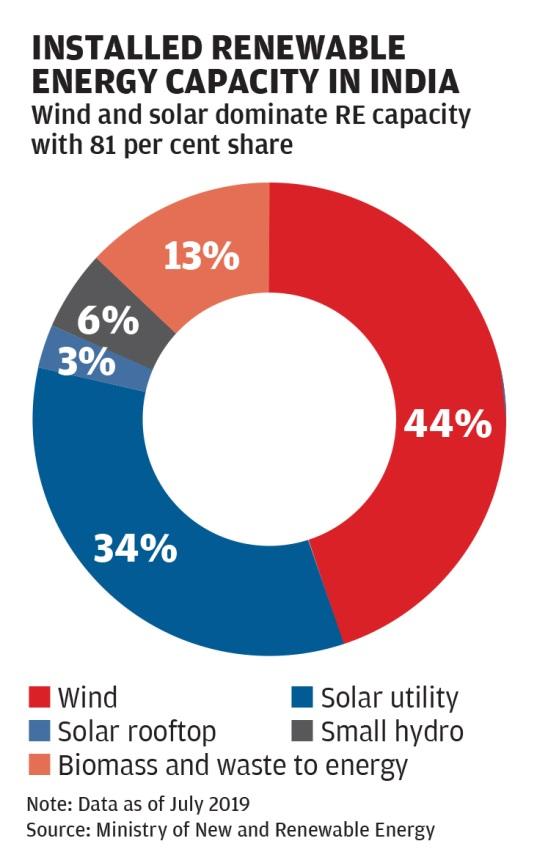

Wind is seen as a source of “green” energy and its capacity was constantly increasing in India between 1985 and 2015; it now accounts for about 4% of all energy in the country; wind also comprises about 44% of all renewable energy in India, according to data compiled by the Centre for Science and Environment.

(From Down To Earth annual report, State of Indiaâs Environment 2020)

The Great Indian Bustard population was shown to have reduced about 82% over 47 years, from 1,260 individuals in 1969 to about 300 by 2008. The bird species is critically endangered and is on the Red List of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. Changes in cropping pattern and local grasslands had already adversely impacted the Great Indian Bustard’s population when the first wind turbines were installed in the Thar region in 2001.

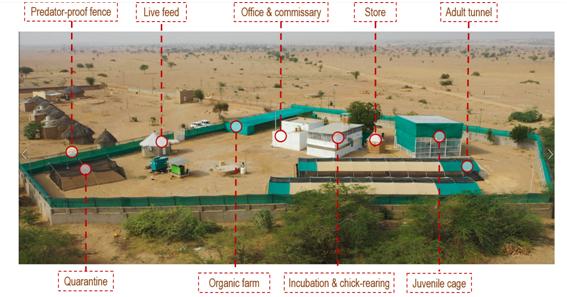

The five-year Great Indian Bustard Species Recovery Programme of captive breeding began in 2019 after earlier attempts at habitat restoration, with funding of Rs 33 crore. The Centre, Rajasthan government and the Wildlife Institute of India, with its team of 17 scientists, are currently engaged in the programme.

Breeding Centre Picture Credit: Harsh Vardhan

Between June and November last year, six Great Indian Bustard eggs were collected. Deputy conservator of forest Kapil Chandrawat of the Desert National Park said since six eggs were collected rather early in the season, the government granted permission to collect more eggs. In all, there are now 10 chicks at the conservation centre at Sam. “They are doing well, gaining weight,” Chandrawat said.

The focal area of the conservation effort is the Desert National Park in Rajasthan, spread over 3,000 sq km. Scientists estimate that there are about 40 Great Indian Bustards in the park area. These large birds – the male weighs about 15 kg and stands about a metre tall – are locally migratory, flying about 100 km away to cultivated patches from October to March, and spending the other months in the arid regions of Western Rajasthan.

Picture Credit: Harsh Vardhan

Environmentalist Harsh Vardhan has long been campaigning for captive breeding of the bird, seeing the sharp fall in numbers over the decades. “International experts from BirdLife International were also involved in the planning of this conservation project. The plan for such breeding was first mooted in 1980, but it took this long for it to be executed. There will be much learning from this for scientists and forest officials,” Harsh Vardhan said.

The sole male chick is named after scientist Asad Rahmani, former director of the Bombay Natural History Society, for it hatched from the egg on July 30 last year, the birthday of the scientist.

Chick. Picture Credit: Harsh vardhan

The endangered bird lays just one egg a year, and since the egg lies in the open grassland, it is an easy meal for predators, like free ranging dogs, lizards, crows, snakes and wild boar. Mortality in the wild is high, at about 40%. In case of severe drought, the bird may not lay an egg at all.

These first-generation human-tended chicks currently being raised at Sam are quite used to touch and even get an occasional massage. Given that they are so used to human contact, they may not be released into the wild, Harsh Vardhan said. The next generation will be tended such that they could be restored to the wild.

Female Great Indian Bustards attain sexual maturity in three years. So these chicks could be expected to bear eggs, and once those chicks hatch, some of them may be released to repopulate desert grasslands. The release will, of course, only happen if a viable number of birds emerge from eggs; also, the next batch of chicks will need to be raised with less human contact to more easily adapt in the wild.

Another of same chick. Picture Credit: Harsh Vardhan

Once the birds take wing, however, they will face a problem if they fly beyond the boundaries of the Desert National Park – the wind turbines. The wind park here is now the largest in the world. The Great Indian Bustards are large and heavy birds; they fly at low heights, and the extensive cables of the grid here are hard for them to see and negotiate. There have been several instances of birds – not just bustards – dying because of contact with high-voltage power distribution lines that form part of the grid.

The wind turbines stand on revenue land, over which the state forest department has no control. WII scientists have been picking up carcasses of birds from under the wind turbines and high-voltage wires, to arrive at an estimate of the number of birds killed. Extrapolating the data, they estimate that 1,20,000 birds are killed after collision with turbines or power distribution lines each year in the Desert National Park and its surrounding area. Wildlife conservationists have urged the government to shift underground the grid and transmission lines to reduce bird mortality.

The government has also asked wind firms to install bird diverters on turbines and wires, and to paint the top of the turbines orange so the birds can clearly see them. Conservationists say regulated tourism must be allowed inside the Desert National Park; although tourists arrive to see the sand dunes and listen to folk music, their entry into the national park is restricted. Conservationists argue that tourists were among the first to note the absence of tigers some years ago in Sariska National Park; regulated tourism does aid conservation efforts.

Picture Credit: Harsh Vardhan

There are nearly 73 villages and settlements inside the Desert National Park. The Thar is among the most densely populated deserts in the world. While the conservation attempt by raising chicks will go some way, the goal of bringing the Great Indian Bustard back from the brink of extinction cannot be met without making its habitat safe for this large bird.

The high number of human settlements has increased garbage and led to growth in the population of pigs. The number of predatory dogs is rising. WII scientists collared one dog to track its prey and discovered that a single dog had killed 22 chinkara in one year.

There are also few forest guards in this region, and the acute shortage means that a chowki (post) might be staffed with just one forest guard. DCF Chandrawat said the Desert National Park currently functions at 50% sanctioned staff strength. The summer temperature in this area is upward of 50 degree C, and the guards work in inhospitable conditions. They are, however, the first to know of changes in the region, and some of them develop a great deal of knowledge with long years of service. There is need to offer greater security and better conditions of work to the guards, so that young people with a scientific bent of mind can take up the task.

Wind Energy Facing Challenges

For about three decades, between 1985 and 2015, wind energy was seen as a promising source of renewable energy and capacity was gradually expanded, to about 37 gigawatt (GW). However, in recent years, there has been a slackening of wind energy projects in India as existing wind farms face operational challenges and reduced liquidity. One major player, Suzlon, now faces debt of Rs12,000 crore.

Government has imposed caps on tariff, making auctions unattractive. Wind is also a rather capricious source of energy, and there is unpredictability about generation. With solar energy generation becoming less expensive, there is competition within the renewable energy sector that puts wind at a disadvantage.

At Kanoi village on the edge of the Desert National Park in Jaisalmer, which once had an abundance of Great Indian Bustards, villagers protest that the wind turbines keep whirring through the day and night, without pause. The ceaseless noise, they say, does not allow peaceful sleep. Villagers showed one of these writers two people who were mentally unwell, and blamed the constant noise from the turbines for the high levels of mental disability.

Picture Credit: Harsh Vardhan

There are other developments, too, that have made the Rajasthan desert less hospitable to these birds – farmers now cultivate crops like “guar”; the millets that were earlier cultivated were also food for these birds. Grazing livestock may also trample over the eggs, which lie in desert sands unprotected.

The state government has now undertaken grassland development schemes and put in place enclosures to prevent predators from attacking the birds at 26 stretches, in lands near the Desert National Park but not belonging to the forest department. Village communities were educated about the conservation attempt, to prevent livestock owners from grazing their animals in these areas.

This year, the locusts have arrived in larger numbers than last year. The chemicals used to kill locusts could also end up harming the Great Indian Bustard, especially if they feed on locusts that have ingested chemicals.

Ashok Mahindra is a chartered accountant with a keen interest in wildlife photography. Rosamma Thomas is a freelance journalist based in Rajasthan.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.