State-Backed Skilling Schemes and Industries Create Army Of Cheap Labour

Workers entering one of the manufacturing unit located in the Gurugram-Manesar industrial belt.

The Indian economy is in tailspin, showed recently released government data, even though the conclusions drawn from this data has not been accepted by the government itself.

A visit to the Gurugram-Manesar industrial belt, hub of the India’s auto mobile industry, highlights the panic of the workers: a slump in demand and sputtering profit rates resulting into waves of job losses and decrease in the wage rates. The later is a reaction adapted by the manufacturing units – both big and small – to drive through the bumpy roads of the crisis.

The industries, to tackle the crisis, are passing the brunt on to the labour forces. What is concerning is that this process is being facilitated by the training programs concerning youth skilling, that are sponsored by the Indian state itself.

Brought In By Congress, Further Greased By BJP

NEEM Scheme, also known as National Employability Enhancement Scheme – part of the state-backed skilling initiatives – was aimed at developing a competent workforce through “on the job training”. Though not much was heard about the scheme in its initial days, according to the workers in Manesar, it has gained a lot of attention in the industrial belt in the past few years.

Launched by the Centre in 2013, the scheme provided the industries with a young labour force, including youths who are pursuing graduation or diploma courses and those who have discontinued their studies.

The youth engaging with the scheme are not considered workers but NEEM Trainees, and they enter into a contract with not the manufacturing units, but the All India Council for Technical Education (AICTE) – a national-level council for technical education – approved third party agencies known as NEEM Facilitators.

The objective of this arrangement was to provide practical training, with the third-party agencies facilitating the same. However, this scheme soon became a source of workforce which is young, cheap, and pliant. “In our initial days, we were taught how the assembly line works in the initial days, then we were provided with our uniform and ID cards. Now, I work on the assembly line and my work hours are same as that of a permanent worker,” revealed Suranjeet*, 20, a NEEM trainee in Honda’s Manesar facility since 2018.

Suranjeet receives a stipend – as prescribed by the NEEM regulations – on par with the minimum wage for unskilled category. In Haryana, it translates to Rs 9,024 per month. For same amount of labour time, a permanent worker is said to make up to Rs. 80,000 to Rs. 90,000. Also, the remuneration Suranjeet receives also does not “attract any statutory deductions or payments applicable to regular employees since the NEEM contract assures training and does not constitute employment,” as the 2013 Gazette Notification of the scheme stipulates.

Around 200 to 300 such trainees employed in Honda, and the facilities of other auto industry leaders, namely, Maruti, Hero, Bellsonica and their vending companies in the industrial belt, have a similar number of trainees, NewsClick has learnt.

“The number of NEEM trainees saw an increase in the last few years,” said Rohit*, 32, a contract worker in Maruti. He added, “There were no such trainees before 2017 in the region, however, now we see them in hundreds in almost all units in Manesar, around us,”

Incidentally, 2017 was also the year when the Modi-led BJP government brought amendments to the 2013 regulations of the scheme and relaxed the conditions for registration of private firms as facilitators. The minimum required annual turnover for the NEEM facilitator was reduced, the training period was increased to 36 months from 24 months, and the minimum age limit required for a trainee was brought down to 16 years, which was 18 years earlier.

This meant that now, through a government promoted scheme – which was brought in by Congress and further greased by the BJP – young individuals soon after completing Grade 10 studies entered the workforce, joined the assembly lines and received the ‘training’ on how to survive the tightly cramped work days of the manufacturing industries.

This should not be confused with providing employability, as the training period is limited to a maximum of three years, after which the trainees are to collect the certificates and vacate the space for the new batch. “I still have one more year of my tenure, however, I don’t know what I’ll do after that. I will have the skills but are there enough jobs?” asked Suranjeet.

Nevertheless, this doesn’t worry the industry and its players, for whom not just the availability of cheap labour has been ensured, but they have also been provided with a workforce which is more controllable. The latter is ensured by the presence of the facilitators and the terms of the contract.

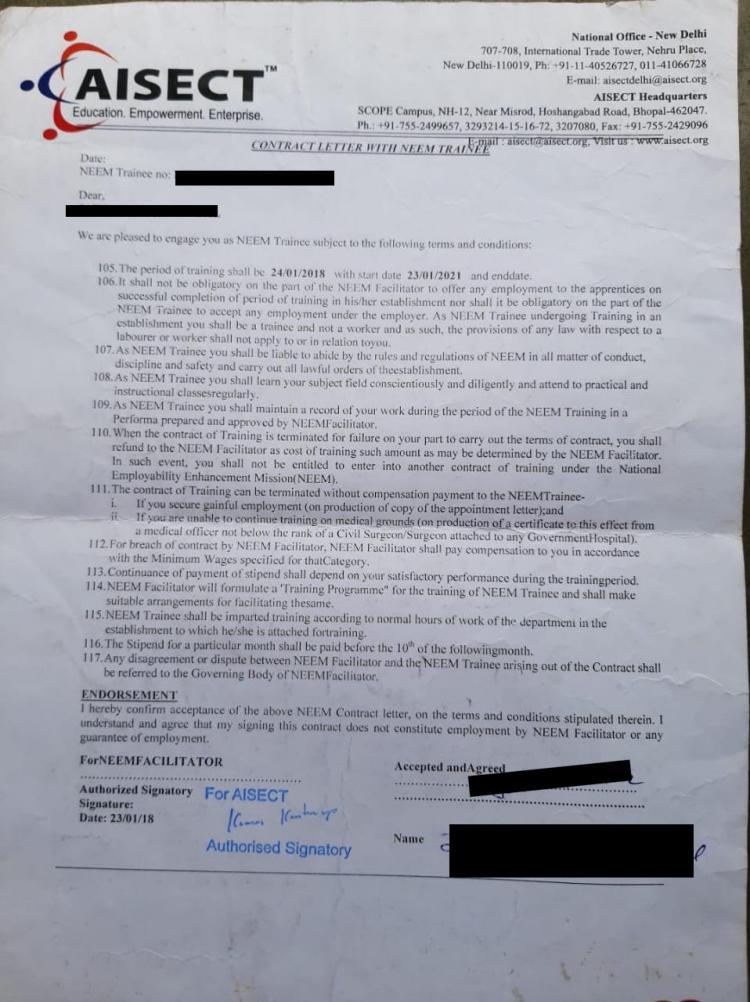

A copy of a NEEM trainee contract has been attached below. It shows how the facilitators ensure the pliancy of the workers.

“When the contract of Training is terminated for failure on your [trainees’] part to carry out the terms of contract, you [trainee] shall refund to the NEEM Facilitator as cost of training such amount as may be determined by the NEEM Facilitator. In such event, you shall not be entitled to enter into another contract of training under the National Employability Enhancement Mission,” says one of the conditions.

A copy of a NEEM trainee contract

In other words, it means that in case a trainee partakes in union activities which the management does not approve of or is found to be disrupting or slowing down the production, not only will they be dismissed at once – with no certificate and future prospectus in hand – but will also be made to carry a financial liability.

The relaxed labour standards invited their misuse. The abuse of the norms became so prevalent that in the month of September, AICTE had to write to all the NEEM facilitators cautioning them against the practice of re-routing the existing employees of industrial establishments as NEEM trainees.

Modi Administration Eased Rules Twice

Craftsmen Training Scheme (CTS) was introduced by the GoI in the year 1950 to ensure a steady flow of skilled workers. 2015 onwards, the scheme, along with other training initiatives, started operating under the PM Modi’s ambitious Skill India mission. Presently, training courses under the CTS are being offered through a network of 15,042 Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) (Govt. 2,738 + Private 12,304) located all over the country, and the total number of trainees enrolled in these institutes is 22.82 lakhs.

However, the course is not followed by permanent employability but further years of on-site training. This on-site training is called apprenticeship, but the result remains the same: easy accessibility of industrial establishments to cheap labour – in this case, with required skill sets.

“For years, production is carried out by putting apprentices on the line. They work for equal hours as regular workers, but receive even less than what a temporary worker earns,” explained Vikas*, 31.

He added, “Young individuals take up apprenticeship as it offers good chance for them to secure a permanent government job later, however, with only few openings and lakhs applying for them, many are pushed again to the temporary workforce.”

rotesting Contract workers in Honda, majority of whom have trained from ITIs and have been working in the facility for the past six to seven years.

Vikas himself did a two-year training course from an ITI in Haryana’s Mahendergarh. But despite acquiring the required skill sets, Vikas failed to secure a permanent job. First in Hero and now working in Honda since 2012, Vikas is one among the flock of skilled temporary workers for whom relief from the clutches of contractualisation still remains a pipe dream.

“The equal work-equal pay demand is wrong because the temporary staff is made to do more than the permanent,” said Vikas. “Still, they [permanent workforce] have a Honda badge on their caps and we don’t. We run Honda’s production but we don’t introduce ourselves as Honda workers, we are the workforce of KayCee [the contracting agency],” he said.

Moreover, the rules to hire apprentices were eased too – not once, but twice – by the Modi administration. In 2015, the 1961 Apprenticeship Act was amended to increase the ceiling of engagement of apprentices in an establishment from 2.5% to 10% of the total strength. This maximum hiring limit was further increased to 15 per cent in September this year, amidst the ongoing economic crisis. Additionally, the penalty for employers were lessened and the provision to reserve 50% of regular jobs for apprentices that an employer train was done away with.

As the economy took a downward ride, the cost of production was needed to be brought down, and the training schemes of the state helped the industries achieve just that.

With NEEM trainees and apprentices being the prominent ones to be engaged in the Gurugram-Manesar industrial belt, other examples of such training schemes also include, Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana and National Apprenticeship Promotion Scheme (NAPS). Both the schemes were launched by the Modi-led BJP government. While the former created a pool of poor, rural, women workers to meet the requirements of the country’s apparel industry, the latter is marked with Modi government further promoting apprenticeship training, under ‘Skill India’, by sharing 25% of the prescribed stipend, to a maximum of Rs 1500 per month, paid to the apprentice.

The promotion of such arrangements had caused ripple effects on the labour force. “Only about 15 to 20% of the workforce in manufacturing units of Manesar remain as permanent, the majority of the rest is on contractual terms,” said Anant, a labour activist, while talking about the changing employee-employer relationship in the region. Anant is also a member of Automobile Industry Contract Workers Union. “Given the vulnerable nature of the contractual job, the temporary workforce is harder to unionise,” he added.

When asked to explain the rise in number of trainees and apprentices, he replied, “This is the reaction of the industries to an economy which is in crisis and to the temporary workforce that is slowly raising its voice.” He added, “Trainees and apprentices are young, often belonging to economic weaker sections and have no experience in trade unionism. As a result, if ever the permanent or temporary staff go on strike, trainees and apprentices come in handy to keep the production line moving.”

This abuse in the manufacturing units is reinforced by the local labour department, that chooses to stay silent, he added.

*Names have been changed.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.