Women in Conflict Zones and Growing Refugee Crisis

In the last twelve months, there has been a significant escalation in conflicts worldwide. If Ukrainian women are being jolted by war today, Afghan women are yet to get over the horror of repeated wars, invasions and atrocities in their country. According to Amnesty International, there are 26 million refugees worldwide, of which almost three-quarters are women and children. And according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNCHR), by August 2021, there were at least 14 lakh Afghan refugees, either internally displaced or in Pakistan, due to repeated conflicts and strife.

The refugees include several thousand Afghan women who fled with their families to Tajikistan, Iran, and Pakistan, searching for food, shelter, and security. “We have become a nation of refugees,” an Afghan woman who had escaped to Delhi told this reporter a long time ago. Her words echo across the years. Fresh waves of refugees fled the country after the United States exited from Afghanistan and the Taliban formed the government.

There are reports that after the Taliban returned to power, more than two million girls had to leave school. The majority of schools have not reopened, though women are reportedly permitted to work in specific sectors. Even in 2017, though education was made compulsory up to class 9, millions of Afghan girls were not going to school. Despite improvements since 2001—for example, a popular Afghan TV channel reported last year that in Herat, the third-largest city, 50% of university enrolments were women—the road was still long and hard.

In December 2001, this writer had visited the Nasir Bagh refugee camp on the outskirts of Peshawar, where several thousand Afghan women had sheltered. They wept as they recounted the horror of seeing family members shot at, girls abducted, and their narrow escape to now live in acute deprivation. “At least we feel safe here,” a mother of three said. But last year the world had to confront images of fearful Afghan women during America’s tumultuous exit from the country. “This is a humanitarian crisis—yet the world is silent,” film-maker Saharaa Karimi wrote at the time.

Afghan women’s rights activist Mahbouba Seraj, who heads the Afghan Women Network, released a video the day the Taliban came to power, saying it was the “worst day of her life” as women feared restrictions and reversals. “There is a void of power as this transition takes place from one regime to another,” she said. “How can they [women] be told they cannot work, be educated, or participate in sports and other activities?’ Seraj said in her video. Echoing Karimi’s feelings, she realised their world had changed dramatically, and for women, for the worse.

When I spoke to Seraj, her voice faltered as she said, “The United Nations had failed us, India had failed us, the whole international community had failed us... We are a broken people, we are a broken country but we need to try and put our pieces together and live on.” Karimi spoke for millions of women caught in conflicts when she said, “We will be pushed into the shadows of our homes and our voices, our expression will be stifled into silence.”

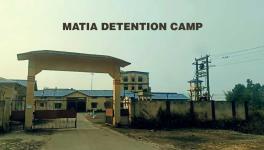

India, too, has witnessed the refugee crisis. Refugees from several countries, including Tibet, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar, have knocked at its doors. Everybody was surprised when Mizoram Chief Minister Zoramthanga refused to deport refugees displaced by the coup in Myanmar. He appealed to Prime Minister Narendra Modi to be “sympathetic” to the refugees, who have fled from the conflict in Myanmar’s Chin state, and have ethnic ties with the Mizos. The Centre had sought to deny the refugees shelter and relief. India is not a signatory to the United Nations Refugees Convention of 1951 and 1967. According to the Mizoram government, there are 24,000 Myanmar refugees in Mizoram as of 12 February, living in more than 140 camps.

The arrival of Rohingya Muslims was another red flag for the central government. Large numbers of Rohingya are women and children, but right-wing Hindutva trolls have accused them of being part of terrorist networks. This swelling tide of refugees faces food shortages and poverty and is routinely subject to sexual violence and physical abuse. The UNICEF has warned against growing attacks against children during this crisis, especially girls.

Sadly, there is little light at the end of the tunnel as, this year, the post-Cold War era turns into a hot conflict in another country. Whatever the geopolitics of invasions and wars, it is women who suffer the most, including during the ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict. On Sunday, the UNHCR said that 14 lakh Ukrainians, mostly women and children, have fled to neighbouring Romania and Poland. They are living in makeshift shelters created in football fields, scarcely able to keep out the bitter cold and snow. Many women are alone during this war, which has had Ukrainian men stay back and fight. This writer’s close Ukrainian friend, Tamara Udartsov, who lives in Geneva, is worried for the safety of her 61-year old father Yuny Udartsov and her mother, who are stranded in different areas. Yuny, a retired judge, was in Kyiv on work when the war began. Tamara says over the phone, “The roads are blocked. No petrol is available and it is very dangerous to drive back home to Donetsk. My 61-year-old mother Olga is in Donetsk all by herself.”

Tamara’s childhood friend Diana Tulub, a lawyer, is also stuck in Bucha with a young child and no news of her husband. There has been intense fighting in the town, and most inhabitants have no water or electricity supply. Tamara and Diana spoke two days ago. “Diana kept sobbing on the phone and was terrified for the fate of her young child,” Tamara says.

War has entered these women’s lives with sirens raging all day, bombings, constant shelling and medicines in short supply and cities reduced to rubble. Tamara says if Russia and Ukraine had resolved their differences in 2014, the crisis would not have escalated to such a level.

The author is a freelance journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.