An Incomplete History of Jackboots on Campus

Jamia students protesting outside Gate No. 7. Image Courtesy: The Indian Express

In December 2019, as it attempted to quell protests against the controversial CAA-NRC-NPR triad, the police took violent action at multiple university campuses. Two months ago, Delhi Police raided Jamia Millia Islamia (Jamia) after it clashed with anti-Citizenship Amendment Act and anti-National Population Register protesters outside the campus. The police surrounded the library, switched off its lights and unleashed lathis and tear-gas canisters on students who had sought refuge inside it.

On 15 December, the police raided the campus and hostels of Aligarh Muslim University (AMU). Of the several students who were grievously injured in the ensuing events, one scholar’s arm had to be amputated. Then on 5 January, the Jawaharlal Nehru University campus in Delhi was attacked by over fifty masked goons who vandalised hostels and assaulted students and teachers. Multiple eye-witness reports accuse Delhi Police of inaction while the goons wreaked havoc.

This article briefly describes infamous acts of violence by security forces in university campuses across the world since World War II. This past offers us succour and strength in our times; it reminds us of how others faced dark times, and often endured. This chronicle of events revisits how ruling regimes have rhetorically constructed students and campuses so that they can be subjected to attacks as ‘enemies of the state’, ‘enemies of the nation’, or of its ‘people’.

The present day is not the first instance of students being grouped together as the ‘Other’—and therefore as justified targets of violence. Regimes have sent armed forces and security personnel into university campuses before. Such regimes have lived on, but in ignominy. By no means an exhaustive list, the authors are attempting to retell a slice of history that is germane to our times.

Prague, 1939

November 17 is celebrated as International Students’ Day in some parts of the world in remembrance of the violent quelling of student protests against the Nazi occupation of (then) Czechoslovakia at the University of Prague campus in 1939. Nine demonstrators were killed by the Nazi invading forces and around 1,200 carted off to concentration camps. The university was always at the forefront of political ferment in the region. It had a role in the Prague Spring of 1968 and the Velvet Revolutions of 1989, which brought down the Soviet-backed communist government.

Poland, 1968

Less celebrated compared with counterparts in Czechoslovakia and France in tumultuous 1968, university campuses in Poland were remarkably active in protests against the Wladyslaw Gomulka regime behind the Iron Curtain. The flashpoint was the censoring of a 19th-century play that celebrated Polish resistance to Russian occupation. A protest movement led by students and prominent intellectuals—some associated with the flamboyant dissident group Komandosi—were demanding greater freedom of expression and right to assemble.

In March 1968, students on campuses in Warsaw, Krakow and other towns clashed with the police. Often, police in plain-clothes attacked campuses, claiming to be ‘worker-activists’, and individuals associated with official communist party organs. Rival factions of the ruling communist party, some opposed to Gomulka, tried to wrest control by accusing ‘cosmopolitans’ and ‘Jews’ (as opposed to ‘patriotic Polish workers’) for sparking the unrest.

In the anti-Semitic purge that followed, Jewish Poles were fired from their jobs and around 13,000 Jews were expelled from Poland, including the sociologist Zygmunt Baumann, a veteran Communist partisan who had fought the Nazis. Student protests behind the Iron Curtain were ostensibly opposed to communist governments, but prominent European ‘New Left’ activists of the era, such as Rudi Deutschke and Daniel Bendit-Cohn were supportive of such protests, including Prague Spring.

Mexico, 1968

The most infamous attack on students in Mexico in 1968 did not occur in a campus. But student protests at campuses and outside had presaged the Tlatelolco massacre, and the American-backed PRI or Institutional Revolutionary Party regime of the time had heavily persecuted left-wing student groups. (Cold War-era American tactics in Mexico included extra-judicial killings, disappearances and torture.) The students were demanding democratic reform, more political and civil liberties and measures to reduce inequality. To crush their resistance the Mexican Army blasted open the doors of the National Preparatory School of San Idelfonso with a bazooka, leading to student deaths.

In September of the same year, the Mexican Army occupied the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Although no students were killed, many were brutally beaten and arrested. This was followed by an attempt by the armed forces to occupy the National Polytechnic Institute, which led to an hours-long violent confrontation with students in which at least ten students died.

On 2 October, a peaceful student demonstration in Tlatelolco, Mexico City was fired upon by security forces. Over a hundred students and bystanders, including children, died in this firing.

[Note: May 1968 in Paris has been thoroughly memorialised in popular history and culture; its social and economic repercussions are felt to this day. But most of these events did not strictly involve armed state action on university campuses, and hence are not included.]

Kent State University, Ohio, 1970

American socio-political movements of the 1960s have an enduring legacy, and students were profoundly involved with them. In continuation of that decade’s anti-war protests precipitated by the American military invasion of Vietnam, students at Kent State had demonstrated in May 1970 against the bombing campaign initiated by the Nixon government in Cambodia. Security forces opened fire on the unarmed crowd and four students lost their lives.

Participants in the protest faced legal action over the decade while security personnel were exonerated of manslaughter charges. The event remains an infamous hallmark of Nixon’s conservative presidency, which included the Pentagon Papers case and ended with the Watergate scandal. Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young immortalised the event in the lyrics of their protest song, Ohio. [This summer I hear the drummin’/ Four dead in Ohio...].

Athens Polytechnic University, 1973

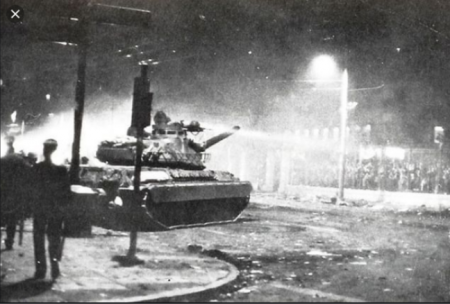

On this day 17 November 1973 the Athens Polytechnic uprising began against the Greek military junta after an army tank rolled over the gates of the University to evict protesting students who occupied it 3 days previously. Image Courtesy: Facebook

Since April 1967, Greece had been under the thumb of a brutal military junta whose leader, Georgios Papadopoulos, a former Nazi collaborator with links to the CIA, fancied himself a ‘surgeon’ operating upon the ailing body of the nation. Civil liberties were severely curbed and political opposition and dissidence led to imprisonment, torture and executions.

Student unrest began on Athenian campuses in 1973, and on 14 November students occupied the Polytechnic School in Athens. A crowd started gathering around the campus. The students set up a rickety radio broadcast calling on all “free fighting Greeks” to join their cause.

After threats by the police failed, the army was called in. Street-lights were turned off. As 17 November dawned, an AMX-30 tank broke through the Polytechnic School gates, while people still clung to the railings. The last radio station broadcast was a desperate emotion-choked call to the soldiers as fellow Greeks and the Greek national anthem. Although no student was killed in this episode, 24 citizens fell to bullets right outside the campus in the run-up. The Greek junta collapsed about a year later.

To this day, 17 November is commemorated in Greek educational institutions. The Exarcheia neighbourhood near the Polytechnic is still a hub of self-organised anarchists and Leftists who now shelter refugees. It remains largely off-limits for police.

Thailand, 1976

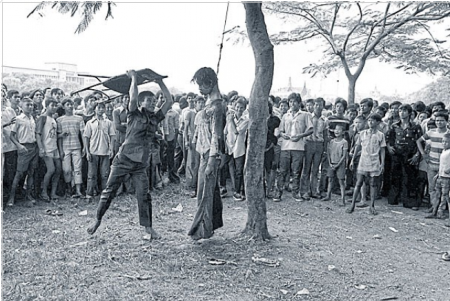

Student protests in October 1973 helped overthrow the military dictator Thanom Kittikachorn who later fled into exile. In 1976, against the backdrop of his return, the students protested again, which led to the events of October 6.

Kittikachorn’s return had created a tense political situation where a supposed fear of communism spread from neighbouring Vietnam and Laos. Even before 6 October many protesters had been killed during demonstrations in the capital.

Outside Thamasat University on October 6, 1976. Photo credit: Neal Ulevich.

The event was a result of a backlash between the left on one side and the ultra right-wing and ultra-royalists on the other at Thammasat University in Bangkok. On that day, the military, police and right-wing paramilitary forces surrounded the university. After ensuring that thousands of students were under siege, the forces assaulted them with for hours M-16s, recoilless rifles and grenades. Official casualties were 46, but survivor accounts said that close to 100 had died. Many students were wounded and over 3,000 arrested. Vigilantes supported the official forces in shooting, assaulting, raping and murdering unarmed students. Till date, no state official has been charged with the heinous crime.

South Korea, 1980 and 1987

Confrontations between security forces of authoritarian governments and students at the gates of university campuses marked South Korea’s blood-soaked path to a liberal democratic polity. One flashpoint, the Gwangju Uprising of 1980 for greater democratic reforms (after dictator Park Chung-hee’s death), was the violent confrontation between students and security forces at the gates of the Chonnam National University. Over 600 protesters lost their lives in the brutal suppression of the uprising.

In the 1980s, students at Korean university campuses were increasingly radicalised, and there was a concomitant rise in state brutality. Students witnessed the disappearance, torture and suicide of their activist classmates as campuses became battlegrounds. In 1986, around 2,000 student-protesters took refuge inside buildings at Konkuk University and barricaded themselves from the police. The force broke through after three days, having cut off water and power supply. Students were traumatised as they were brutally beaten even while being dragged away in police buses.

In June 1987, a movement for democracy and against the ruling military regime was galvanised when university student Lee Han-yeol was killed by a tear gas shell that penetrated his skull outside the gates of the Yonsei University, Seoul. Eyewitnesses said that the police deliberately aimed at the protesting students instead of shooting in the air, as is the norm. The students had been demonstrating as part of a nationwide stir.

Earlier, another student had died during police interrogation. The movement eventually led to democratic elections and other political reforms. Korean protest songs from the period, such as the March of the Beloved, have made their way into the recent Hong Kong protests. The song was originally composed for the posthumous wedding of an activist couple killed in the Gwangju uprising of 1980.

The events of 1987 in Seoul have been captured in the 2017 Korean film, 1987: When the Day Comes.

There have been violent raids by security forces in Asian countries too, such as in the Philippines. The recent Hong Kong protests had large student participation, and involved the siege of two campuses, the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Surely instances from the Middle East and Africa would have enriched this piece—as would have more instances from India that have been skipped. But then such an accounting of memories and history is, by its very nature, a collective endeavour.

Suraj Gogoi is a doctoral candidate in the department of sociology at the National University of Singapore and Krishanu Bhargav Neog is a doctoral candidate at the Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.