Déjà Vu -- A Film That Depicts Chilling Effects of Corporate-Contract Farming

Image Courtesy: Twitter/@KisanSabha

Tomorrow the Hindi version, “Anndatta” will be screened at the Ramlila Maidan for leaders of the Sanyukta Kisan Morcha and Bharat Kisan Union (BKU) on the eve of the massive pre-election protest at this historic venue. The 70 minute documentary draws parallels with what Indian farmers are today resisting; USA’s “parity price” that was snatched away is the same as the “Minimum Support Price” (MSP) that the Indian farmers are today demanding

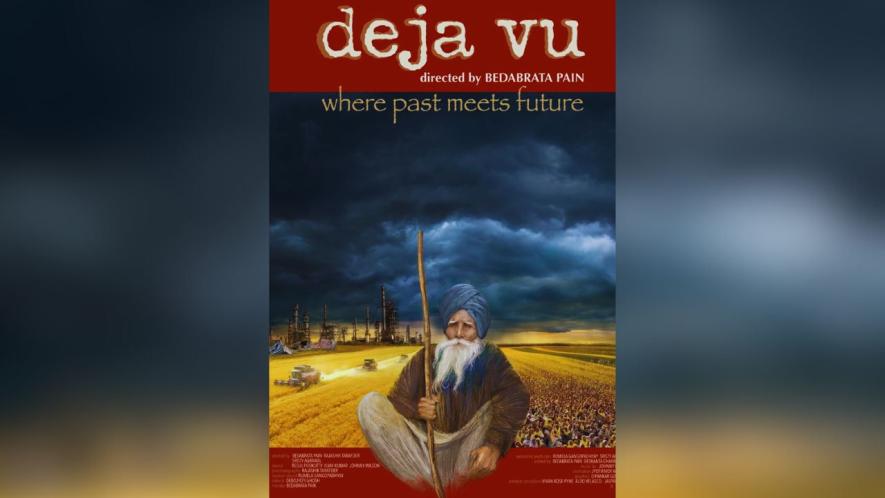

The documentary film –titled ‘Déjà vu -Where the past meets the future’– in English– directed by national award-winning film-maker & scientist Bedabrata Pain is being screened across India. The documentary, which was released recently (and shot during the Covid-19 pandemic), remains particularly pertinent today with the resurgence of the farmers protest converging on the capital on March 14, 2024. Among a slew of demands, is the one demanding a law guaranteeing Minimum Support Price (MSP) from the union government. Rajashik Tarafdar, Rumela Gangopadhyay and Sristy Agrawal, two physicists formed part of the team that undertook the journey with sound, camera and lights all being simultaneously handled.

With a raw and haunting landscape as their set, the team spoke to small farmers in the US. The team, which took a 10,000 km journey through the heart of rural America, met small farmers across the spectrum covering dairy, grain, poultry, beef and hog along the mid-western agricultural states. The film highlights these eye-opening accounts of America’s small farmers who speak of the takeover of their land by the banks, their entrapped indebtedness caused by a model that was sold to them as “free market” coldly evolving into large “monopolies” (whose aim is simply to squeeze out both independent farming, quality produce and the rural farming community as a whole.

This is what slowly happened to small farmers in America after the “opening up of United States farm sector forty years ago”. Trapped by the neo-liberal lingo of “free and open markets”, “market reforms in agriculture” (uncannily familiar with the current ruling regime’s false promises and their supportive economists who dominate media space here in India today). In the US, farmers spoke contemplatively and with pathos of how they had been priced out by big companies, with the full support (read connivance) from the government, in the name of market reforms. The film reveals a sharp and necessary perspective, gentle and convincing through the experiential narratives of these US farmers, explaining how the agricultural and poultry sectors were insidiously taken over by private companies and corporative.

From the start, and interspersed throughout, this film, is powerful footage of the Indian farmer from the then and ongoing (since 2020) protests in India. Begun on November 26, 2020 against the three contentious farm laws, the accounts highlight how the farmers have been battling against contractual farming and corporate-government control over farming. In September 2020, without any discussion with farmer unions, organisations or leaders, without any debates in Parliament, these three laws were passed by the Modi-BJP-led Indian Parliament within minutes. Determined protests by farmers from across India gheraoing the Indian capital –Shambhu, tekri and Ghaziabad borders –the farmers sat through inclement weather, put up with brute repression and lost 700 lives. Then as now, farmers were demanding not just the rollback of these laws (which finally happened) but also MSP as a legal statutory right, the withdrawal of all cases and pending loans, the settling of unfair electricity dues etc.

The three black Farm Laws were introduced by the Modi-led government under the garb of prosperity, reforms and the involvement of big companies in farming being the solution to the crisis that the farmers faced.

| “2024 began with farmers all over Europe demonstratively raising their voices in protest, while farmers in India re-launch a protest march to Delhi alongside other demonstrations, with MSP in the forefront of their demands.

“The documentary began in 2021. Barely two months since the launch of the farm laws in India to promote market reforms. In the middle of Covid-19 and a frigid American winter, four Indians were on a ten- thousand-kilometre drive through the farming heartland of America. Because, as it turns out that four decades ago, similar market reforms were ushered in in America. A more classic case of “back to the future” perhaps could not be found. How did the reforms turn out? Who benefitted? Who lost out? Is it the farmers, the consumers, or the corporates? What impact did loss of MSP or ushering in of contract farming have on farmers? Through personal experiences and human stories of small farmers in America, Deja Vu is a chronicle of a four decade long history of a much-trumpeted elixir – and a cautionary tale for India. Déjà Vu is the confluence where past meets future.” (The official write-up about the film) |

Back to Deja Vue. The film has powerful recordings of American farmers supporting the Indian farmers, stating that “What India is witnessing and is being told, we already heard here and are living through the consequences. It is Déjà vu”.

“Globalisation of the Hope, Globalisation of the Struggle.” That is the slogan of Via Camesina, a global movement for food security and farmer’s rights.

American farmers described the changes being imposed on the farmers in India as disastrous for small farmers and pro-big corporations. Hailing the Indian farmers for recognising these tactics in time and not mindlessly accepting the promises being made by the government, the American farmers were saying, “When a neighbouring farmer is in distress, we are able to come together, provide food and other supplies and assistance but when it came to coming together and launch a mass movement, we failed.” For them, the resistance shown by the Indian farmers against the BJP-led government-corporate nexus was a learning experience for American farmers. The documentary powerfully depicts how the protest by Indian farmers finds s resonance with the farmers in the US and how it is through such resistance that a grim future for India’s agricultural sector can be avoided.

The crisis faced by the American farmers:

The film documents the challenges that came along with the US adopting the “open market system.” Over the period of forty years or so, as agriculture was opened up for free market, the entire sector went into hands of 3 to 4 big corporations and small farmers got wiped out. Land ownings got consolidated and captured by “market investors” like Bill Gates who have nothing to do with farming of one kind or another,

As shown by the film, corporatisation of agriculture, including the dairy, poultry and other sectors began in the US in the 1980s, as part of the drive for a neo imperialist globalisation. These “reforms” then resulted in cropping up of issues such as monopoly of corporates, lack of control over price, inflation, increasing loans amounts and farmer suicides. Left with no options, the farmers in the US were compelled to opt out of the agricultural sector and join meagre and manual jobs for their survival. The community disappeared, families broke up, farmers took their lives using the gun or pills. One chilling comment came from a surviving farmer who said that often farmer deaths were before tractors or farm implements so that these could be passed off as accidents “for the insurance companies.” They even died for family,” said a protagonist in the film.

“Old Mc Donald had a farm” is a ditty/nursery rhyme we were brought up with in the English speaking world. “Had” being the operative word. For the past three decades and more, the US farmer is part of a visible trend of farmers opting for other jobs, such as janitors, after being left with no option. The documentary was shot at Hunter in Oklahoma, Columbia and Laddonia in Missouri, Fairfield, Clearlake and in Iowa, Wonewoc, Kendall and Madison in Wisconsin, Ashland in Nebraska, St. Francis in Kansas and Boulder in Colorado.

Interviews of Kansas and Colorado’s ex-grain farmer and now-cattle rancher Mike Callicrate, Missouri’s small farmer and ex-Lt. Gov of Missouri Joe Maxwell, Wisconsin’s exdairy farmer Jim Goodman, Iowa’s grain farmer Patti and George Naylor and Oklahama’s grain farmer Zane Blubaugh, among others were also a part of this documentary.

The documentary tracks the erosion of policy safeguards like “parity pricing” (similar to India’s MSP) that were in place in the US prior to the opening up (sell out) to the market corporations. What makes the film special is the scientific attention paid to data, attractive and simple graphs that explain the facts as they should be told not how the government and large corporations want them. USA had the equilavent of MSP in “parity pricing in the country. This ensured that prices for the produce accounted for cost of production and risks of the farming business; all in all a guarantee that ensured that farmer communities’ rural incomes could be maintained at the same levels (standard of living) as their urban counterparts. In the dairy sector for example, there was a fixed floor price compulsory for any buyer. Not just for government procurement but anybody who wanted to buy milk had to pay the “market floor price.” Most crucially community (farmer) owned “elevators” ensured storage of farm (grain) produce so that the farmer/agricultural community could collectively (co-operatively) store this grain after harvest (when typically prices fall (are low) and ensure sale (and comfortable margins/profits) by sale when prices recover the expenses. One of the insidious steps taken by the government-corporation nexus when “reforms” were brought in was that this co-operative elevator was “taken over by one owned by a monopoly corporate who pressed farmers to sell when prices were low, squeezed other distributor buyers out of business blackballing them!

As soon as the “reforms” were pushed and large sections of the rural community “bought” into the rhetoric, a monopoly of big corporates followed. Soon only a handful of large companies remained it power and they squeezed out smaller independent distributor outlets, forcing all farmers and dairy producers to sell their produce at prices lower than they spent on producing the same.

“Get Big or Get Out”, was the ominous slogan of this model of “development that concentrated, land and wealth in the hands of a few. Governments, beholden to a wider democratic populace for the vote, used tax payers’ money to bail out these corporations, offer otherwise unsustainable loans presenting a nexus between large money, corporates and government that we have seen evidence of in India today.

Soon, before even the farmers knew it, these (three or four) big corporates were soon showed to have an overwhelming control everything from input to output of produce, from fertilizers to farming machines. Notably, statistics show that the American farm population has gone down from some 30 million in the 1950s to less than 2 million today

Corporation control over poultry and farming saw a similar take a squeeze. Among the worst shots in the film (for animal lovers and humanists alike) is how the entrance of big corporates and domination of corporate control influenced the (misery infested) lives of poultry and livestock. Animals –instead of free range on the farm — were now being kept in concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), with no place to live, breathe or defecate. Farmers were given contracts by the big corporates to help grow the livestock at a particular price. To build these CAFOs, farmers would take loans. Even when the farmers were the ones feeding, cleaning and taking care of the livestock, chicken and pigs, they were not given adequate prices. It was they who had to but all the inputs, while the livestock was owned by the corporates themselves. Thus, from 80% of meat packaging to 70% of seeds, everything came under the control of big corporates and the farmers were not left with anything.

Once a government embarks on this road of policy sell out to corporate control over land and farming, small farmers (and others) are slowly left with no choice but to quit agriculture to survive. In most cases, the lands owned by these farmers were either sold by them or confiscated by the banks due to the farmers being unable to pay back the money loaned. These lands were then be bought and owned by big corporates. Graphs depict this with powerful human accounts illustrating the wider tragedy of the loss of the farming community. In the film, Déjà Vue.

The 2020-21 farmers protest in India:

With this powerfully shot footage of experiential accounts and hard data of farmers of the USA, Deja Vue then draws parallels with the farm protests in India.

First, the three farm laws had been introduced by the Modi led government in 2020. These laws were-The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance and Farm Services Act, and The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act.

Unprecedented protests had been organised by the farmers, expanding for more than one year, during the Covid pandemic.

Here’s a brief about these three laws:

- The Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act provides for setting up a mechanism allowing the farmers to sell their farm produces outside the Agriculture Produce Market Committees (APMCs). Any licence-holder trader can buy the produce from the farmers at mutually agreed prices. This trade of farm produces will be free of mandi tax imposed by the state governments. (This essentially means no protected price, no MSP with powerful corporations calling the shots)

- The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement of Price Assurance and Farm Services Act allows farmers to do contract farming and market their produces freely. (The experience of potato and tomato farming by Pepsi in Punjab –also powerfully documented by first person accounts in the film—belies the title and intent of this law.

- The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act is an amendment to the existing Essential Commodities Act. This law now frees items such as foodgrains, pulses, edible oils and onion for trade except in extraordinary (read crisis) situations. This is a disaster for food security and can encourage hoarding.

Reforms or Disaster?

While the Modi government presented these aforementioned laws as reforms akin to the 1991-opening of the Indian economy linking it with the globalised markets, the farmers were stoically against the increasing involvement of private sector. Even as the union government had tried to build the narrative of the three laws opening up new opportunities for the farmers so that they can earn more from their farm produces, the Indian farmers remained firm and kept protesting against the same.

In 2020-21, these voices of protesting farmer leaders and the community, including women were heard largely through the media. This is because the commercial legacy media, a beneficiary of government and corporate advertising, visibly diluted reportage. This documentary re-visits the farmers protest, spearheaded by the Samyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM), that were taking place in the Singhu and Tikri borders in Delhi. Many protesting farmers and their words found space in the film, including that of Rakesh Tikait, an Indian farmer rights activist and national spokesperson of the Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKU).

Tikait’s rustic explanation of what a complicated “contract” with dozens of clauses that can only harm the interests of an unlettered farmer –given the uneven and hopelessly imbalanced playing field – comes across powerfully in the film.

The film ends with an expression of support from American farmers to the protesting farmers in India. Appreciating the undeterred strength of the Indian farmers who have been more instinctively prescient perceiving the disasters in store for the rural farming community, a message of pathos and solidarity is conveyed from across the seas, in this film.

In November of 2022, more than one year after the three farm laws were introduced, the union government had to capitulate and roll back the laws. As PM Modi announced the same, he stated that his government, despite best efforts, “could not explain to a section of farmers that the laws were in the larger interest of the farmer community. “

The current crisis facing the protesting farmers in India:

A report by Scroll, in 2022 reveals that the Punjab government had announced an MSP of Rs 7,275 per quintal for moong dal. However, data from Punjab State Agricultural Marketing Board shows that in 2023, 96.5% of moong was sold to private buyers for a price almost entirely below the MSP that had been officially declared.

The report also highlights how in February, 2024 farmers in Punjab’s Abohar had dumped truckloads of kinnows in front of the district collector’s office in protest. The farmers had alleged that Punjab Agro Industries Corporation had purchased small quantities of kinnows from a few farmers, leaving others at the mercy of private traders who were offering less than Rs 10 per kg.

The MSP regime is meant to act as a safety net with the government either directly buying a crop from farmers if the market price falls below the minimum support price it has set or enabling purchase after collective storage when prices are rationalised in favour of the farmer. This demand is based on the formula recommended by the Swaminathan Commission, which proposed that MSP should be fixed at 1.5 times the cost, or ‘C2+50%’. Thus, if cost of cultivation can be brought down, the MSP can be aligned closely with normal open market prices. This will ensure that, in any year, for most crops, market prices are remunerative.

Since February 13, 2024 farmer unions and farmers have been protesting against the Modi government to demand a law on MSP. On February 18, during the fourth round of talks held between the farmer leaders and union ministers in view of the farmers protest, the union government had tabled a proposal on the issue of a minimum support price guarantee.

In the said proposal, it was proposed that government promoted cooperative societies like NCCF (National Cooperative Consumers’ Federation of India) and NAFED (National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India) would buy three pulse crops, maize, and cotton at MSP for five years after entering into a legal contract with farmers. The same proposal was rejected by farmer unions two days later by calling the same to be an “eyewash”. Jagjit Singh Dallewal (convener of SKM non-political), one of the organisations super-heading the current ‘Delhi Chalo’ protest, had deemed the said proposal to not be beneficial for all farmers and there was no justification for providing MSP for only 5 crops out of the previously demanded 23 crops. Dallewal had further stated that the said proposal was also a form of contract farming and sustainable income to farmers cannot be guaranteed from the same.

Details of the proposal can be read here.

Details of the reasons behind rejection of the proposal can be read here.

The Indian farmers continue to protest and raise demand for a law on MSP. After the rejected of the proposal, almost a month has passed. No more talks were held between the union and the farmers. No announcement has been made by the Modi government regarding MSP.

Indian farmers not alone in leading protests against government:

Globally, farmers have been facing a crisis over decades. Demanding MSP among other guarantees, they highlighted that the abdication of any fair governance by governments in India towards agriculture. In short, the income derived from agricultural activities is not sufficient enough to meet the expenditure of the cultivators. According to latest National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data released on December 4, 2023, at least one farmer died by suicide every hour in India. In fact, farmers’ suicide deaths have been showing an increasing trend since 2019 when 10,281 deaths were recorded in NCRB data. In the year of 2022, a total of 11,290 farmer suicide cases were reported from across the country.

The crisis that farmers face today is not limited to India. In the past month, farmers in France, Germany and Europe have also been protesting against their government’s agricultural policies. Farmers in France, the EU’s biggest agricultural producer, state that are not being paid enough and are choked by excessive regulation on environmental protection. Demonstrations erupted across Europe, with farmers forming blockades, dumping manure in cities, and egging government buildings. There have also been protests in Italy, Germany, Spain, Switzerland and Romania. Farmers in Poland have been at the forefront of opposition to grain arriving from neighbouring Ukraine, forcing the government back to a negotiating table. In Germany, the protesting farmers blocked highways last month for a week to rail against cuts to subsidies for their diesel. Thus, it remains crucial to see that the issues that the farmers in India are facing, are protesting against, do not exist in isolation.

Why is Déjà vu so important?

‘Déjà vu’ is an eye opener for the Indian urban audience, especially policy makers and those who seek votes from the people. By powerfully, and empirically depicting the consequences of a “free market and involvement of corporates in the farming sector”, the film sets the narrative right by painting a clear, albeit grim, picture of the dire effects of corporatisation of agriculture. While giving an interview in 2023, filmmaker Pain and pointed to the relevance of this documentary in India even after the farm laws have been repealed and stated that, “The issues have not gone away, nor has the question of MSP – a major demand on which nothing has moved.”

On March 13, the documentary will be screened for the Indian farmers at Ramlila Maidan in Delhi, where some of the farmers are protesting as a part of the ‘Delhi Chalo’ protest. The said screening for the farmers was initiated and is being coordinated by Citizens for Justice in Peace. The film, which was in English, has now come out in a dubbed Hindi version with the help of Naseeruddin Shah (Anndatta). It will soon be dubbed into other national languages of India as well. Multiple screening of the film has already taken place. On March 9, the documentary was screened at the Mumbai Press Club on March 9, 2024. Director Bedabrata Pain, Filmmaker Anand Patwardhan and AIKS (All Indian Kisan Sabha) President Dr Ashok Dhawale had also briefly addressed the gathering after the screening.

Prior to the same, an online screening of the film had also been organised by Citizens for Justice and Peace on March 6. The said screen was attended by Director Bedabrata Pain, Andrea Ferrante (Italian farmers rights activist), Raj Patel (Activist, Author, Academic from University of Austin) and Nico Verhagen (one of the founding members of La Via Campesina). Indian farmer leaders such as Vijay Jawandhia (senior farmer leader from Wardha, Maharashtra and a part of Shetkari Sanghatan), Sonu Singh (young activist of BKU, daughter in law of Tikait family) and Gaurav Tikait (President of the Youth Wing of BKU) were also part of the screening and discussion. Chukki Nanjundawamy of the Karnataka Rajya Raitha Sangha had helped CJP organise this online screening.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.