DVC, a Legacy at Risk Amid Privatisation Concerns

There is growing apprehension among the workers of Damodar Valley Corporation (DVC) in West Bengal, India’s first multipurpose river project post-Independence, that it may be handed over to private corporate entities.

Established to generate thermal and hydroelectric power, provide irrigation facilities, and maintain soil conservation across the vast Damodar River valley in West Bengal and Jharkhand, DVC has served the nation for 76 years. However, recent actions by the National Democratic Alliance-led Central government have sparked fears of privatisation among DVC employees and management.

Several DVC officials have expressed concerns that the Central government, despite their resistance, may push forward with plans to privatise the corporation. This move has raised uncertainty regarding the pensions of retired workers, further fuelling a sense of unrest.

Left-wing trade unions, led by the Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), have united to resist the privatisation efforts. Hundreds of retired workers have also joined the movement, demanding that the DVC Act, enacted by the Indian government on July 7, 1948, be upheld and that the rights of workers be protected.

Protests are intensifying across all DVC plants as workers remain steadfast in their commitment to prevent the weakening and potential privatisation of this vital public sector entity.

The Glorious History of DVC

The Damodar River originates from Palamu on the Chhotanagpur Plateau in Jharkhand and flows into the Hooghly River after traversing approximately 290 kilometres through Jharkhand and West Bengal. Historically, the Damodar River Valley was prone to devastating floods, with the flood of 1943 being particularly catastrophic.

In response, the Bengal government established the high-powered "Damodar Flood Enquiry Committee." The committee recommended the formation of a body similar to the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) in the United States. Consequently, W.L. Voorduin, a senior engineer from TVA, was appointed to study the flood-prone areas of the Damodar Valley. After thorough analysis, he proposed a multipurpose plan aimed at achieving flood control, irrigation, power generation, and navigation in the Damodar Valley.

Following India's independence, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru entrusted the renowned astrophysicist Meghnad Saha with the task of implementing this vision. Under Saha's initiative, a 10-member committee was formed, with the Maharaja of Bardhaman, Uday Chand Mahtab, serving as chairman.

The committee conducted extensive on-ground assessments and proposed a comprehensive plan for the Damodar River, in line with Voorduin’s recommendations. The Central government approved the proposal, leading to the establishment of the Damodar Valley Corporation (DVC) through a joint effort by the Central government and the state governments of West Bengal and Bihar (now Jharkhand).

On July 7, 1948, the Central government passed the Damodar Valley Corporation Act, marking the inception of India’s first multipurpose river valley project.

The construction of DVC's infrastructure began with the first dam at Tilaiya on the Barakar River, completed in 1953. This was followed by the Konar Dam in 1955, Maithon Dam in 1957, and the Panchet Dam in 1959. Concurrently, a barrage was constructed on the Damodar River at Durgapur in 1955, along with a 136.8-km-long left bank main canal and an 88.5-km-long right bank main canal.

These dams have not only mitigated floods but have also provided irrigation water to 3.64 lakh hectares of agricultural land in Jharkhand and West Bengal. In West Bengal, districts such as Bankura, Purba and Paschim Bardhaman, Hooghly, and parts of Howrah benefit from the irrigation water supplied by the Durgapur barrage. Since 1964, the state’s irrigation department has managed the Durgapur reservoir constructed by DVC, which remains a vital resource for numerous farmers.

In addition to flood prevention and irrigation, the reservoirs supply essential water to heavy, medium, and small-scale industries in Jharkhand and West Bengal and provide drinking water. Hydroelectric power generation was also initiated using these reservoirs, with ongoing electricity production at Tilaiya, Maithon, and Panchet dams in Jharkhand.

To further support industrial and community development, DVC established multiple thermal power plants in Jharkhand and West Bengal. The first was at Bokaro, followed by the Durgapur Thermal Power Station in West Bengal. Subsequently, additional plants were constructed in Jharkhand at Chandrapura and Koderma, and in West Bengal at the Durgapur Steel Power Station in Andal, Mejia Thermal Power Station, and Raghunathpur Thermal Power Station.

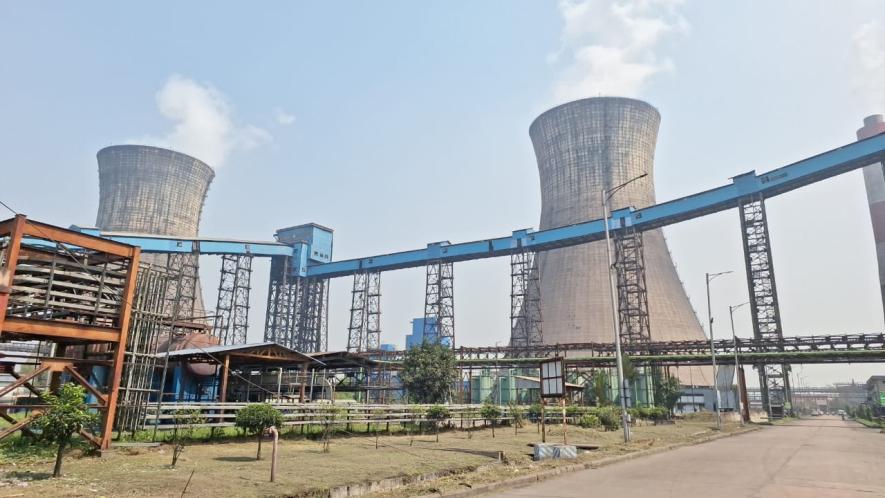

DVC’s Mejia Thermal Power Station

Although the Durgapur Thermal Power Station was shut down several years ago, it is currently being renovated with a target of generating 500 megawatts of power per day. Additionally, electricity is being produced at two joint venture centres with Tata at Maithon and with SAIL in Bokaro.

Beyond its productive initiatives, DVC is actively involved in various social welfare efforts. These include ongoing activities, such as tree planting for soil conservation in the areas surrounding DVC projects, constructing new metal roads, providing drinking water to populated villages, and building community halls for cultural activities.

DVC’s Legacy, Challenges and Concerns

The glorious tradition of the Damodar Valley Corporation (DVC), encapsulated in its motto "For the Service of the Nation," remains largely upheld by the public sector. However, DVC workers are increasingly skeptical about how long this legacy can be sustained.

As an autonomous body composed of representatives from the Central government and the state governments of Jharkhand and West Bengal, DVC operates under the directives of the Union Ministry of Power. In recent times, the Central government's control over DVC has intensified, leaving senior management officials feeling constrained by strict regulations that hinder their ability to make independent decisions.

Samir Bayen, leader of the DVC Sramik Union, affiliated with the CITU, expressed concerns to this writer about the growing influence of the Central government. Suman Goswami, secretary of the DVC Sramik Union at Mejia Thermal Power Plant, noted that the Centre did not provide any financial support to DVC. Despite this, DVC has consistently generated profits through the diligent efforts of its workers, who remain committed to the corporation’s founding principles.

In the last financial year, DVC reported a profit of ₹700 crore, with ₹295 crore coming from the Mejia Thermal Power Plant alone. Workers fear that the Central government may be attempting to sell this profitable public sector entity to private corporate houses.

These concerns were further heightened on July 18 this year, when Union Power Minister Manohar Lal Khattar visited the DVC headquarters in Kolkata. During his meeting with the DVC Chairman S. Suresh Kumar and other senior officials, it was suggested that DVC's power generation, distribution, and transmission operations should be separated.

"This proposal has sparked concerns among employees and management alike that such a move could lead to the privatisation of DVC operations," Arindam Banerjee of the Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC)-affiliated DVC Karmachari Sangha, told this writer.

Several DVC workers pointed out that while the cost of power generation was high, the real profit was in transmission, a sector in which DVC excelled. DVC's transmission network is the corporation’s primary revenue source.

Movement organised by CITU’s DVC Sramik Union at MTPS

Currently, DVC's thermal plants and hydroelectric projects together produce an average of 7,209.9 MW of electricity per day, with 7,062 MW from thermal plants and 147.2 MW from hydroelectric projects. DVC operates ten 220 KV and twenty-four 132 KV substations.

The corporation sells electricity at very low rates to Railways and various industries. Workers fear that if the transmission sector is handed over to corporate houses, DVC will get weakened, potentially leading to the eventual sale of the entire public sector entity as a "sick industry."

Following the publication of the Union Power Minister's suggestion to separate DVC's operations, unions affiliated with INTUC and other Left-wing trade unions, along with the pensioners' forum, staged a protest in front of DVC's headquarters in Kolkata. The agitators argued that the proposal violates the DVC Act of 1948.

Swapan Kumar Mohinta, a retired worker, expressed concerns about DVC's decision to hand over ₹80,000 crore of workers' provident fund to two banks, raising uncertainty about future pension payments.

"We know that every employee and officer of this public sector belongs to the same family. Now there is an attempt to break this relationship. It must be stopped through a united movement," he said.

The reality is that while DVC had 10,000 permanent workers in 2000, this number has now dwindled to 3,200, despite a significant increase in electricity production across DVC's thermal plants. Bayen said after the retirement of skilled workers, new permanent workers with similar skills were not being appointed, leading to an increased reliance on temporary workers.

Shantimoy Das, secretary of the Mejia Thermal Power Station Construction Workers Union, highlighted the growing lack of safety within the plant. In the past two years, seven contract workers have died at the Mejia plant.

Mejia thermal power station coal handling area where the contract workers are repeatedly losing their lives in accidents.

"The DVC authority does not take responsibility for us. We have to work at the discretion of contractors, who pay us only ₹12,000 to ₹14,000. No gratuity is paid after retirement. It is very risky work," Das added.

Goswami said DVC used to determine employee salaries, but now the Centre is taking over this responsibility. He also mentioned that workers used to receive free electricity in their quarters, but now they must pay 1% of their basic pay. There was also an attempt to install smart meters, which was prevented through a workers' movement.

Shockingly, workers were required to pay a 20% tax on the gold coins given to them as mementos for their service to the nation last year.

The social work that DVC once carried out has also been discontinued. Achinto Das, a resident of the Mejia Thermal Plant adjoining area, alleged that around 60 people in Lotiayaboni village, near the plant, died from respiratory problems and cancer due to ash emitted by the power plant.

"Now this village has become deserted. For their safety, DVC is not taking proper initiative to relocate them and build a new residential area," Das claimed.

It is also alleged that DVC’s reservoirs are not being maintained regularly, leading to a decrease in their water storage capacity. As a result, even minimal rainfall causes the reservoirs to fill up quickly, prompting the authorities to release water, which creates flood-like situations at regular intervals.

Mrityunjoy Maji, secretary of the Kamgar Sangha, affiliated with the Indian National Trinamool Trade Union (INTTUC) and Prasanto Mandal, secretary of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh- Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS) both stated that they do not yet have complete information, but they would protest if necessary.

In response to workers’ concerns, Chief General Manager Prodyumno Shah and Deputy General Manager (Administration) Niroj Sinha of DVC's Mejia Thermal Plant said everything depended on the Centre’s decision and declined to make further comments.

Workers at DVC are left questioning whether the commitment made by India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, that this multipurpose project would serve the nation, will remain intact.

The writer covers the Jangal Mahal region for ‘Ganashakti’ newspaper in West Bengal.

(All pictures taken by Madhu Sudan Chatterjee)

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.