From Valmiki, Tulsidas and Ramanand Sagar to Rama

Image Courtesy: The News Minute

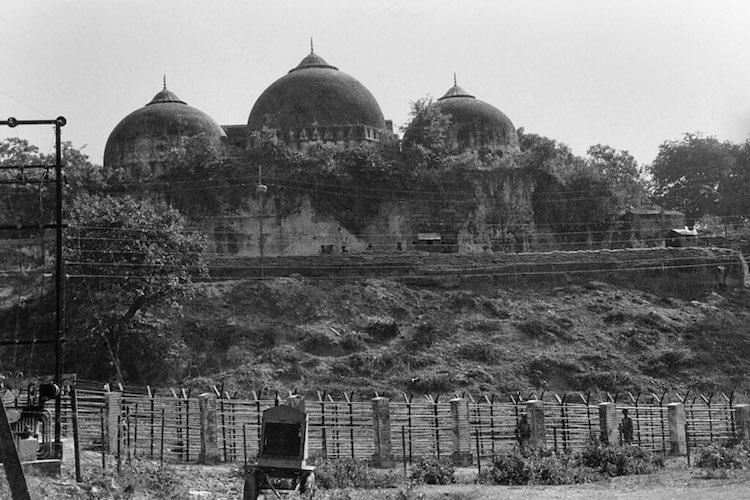

On 5 August, the government plans to lay the foundation stone of a temple in the name of the Hindu god Rama at the site where the Babri masjid once stood. This has immediately sparked two new controversies. Some Buddhist groups have claimed that the remnants of a Buddha Vihara were found at the site of the mosque as it was being levelled to build the temple. The Supreme Court has rejected the public interest litigations that sought to excavate and preserve these artefacts.

Perhaps Ayodhya’s archaeological truths will forever remain buried, whether or not they are of Buddhist origin. The other controversy was started by the Prime Minster of Nepal KP Sharma Oli, who has claimed that “Ayodhya”, the place where Rama was born, is in Nepal’s Birgunj district and not in the northern province of Uttar Pradesh in India. The timing of his remark is such that he was criticised even in Nepal. His office clarified later that there was no intention to hurt religious sentiment.

Yet this is not the first time that claims and counter-claims have been made around Rama and the geographical sites that could correspond to places described in the epic Ramayana. When the government of Maharashtra started publishing the collected works of BR Ambedkar in the 1980s, there were protests against his book, “Riddles of Rama and Krishna”. Ambedkar has critiqued Rama, whom many Hindus revere, for killing Bali, a popular king in the epic. Bali was killed from behind a tree by Rama. Similarly, Shambuka, who is described as a Shudra ascetic in the Ramayana, was killed by Rama for breaking the rules in attempting penance (tapasya). Rama’s treatment of Sita is also criticised by Ambedkar, for forcing her to go through a literal trial by fire and for her banishment.

Incidentally, before Ambedkar, Jotirao Phule also had underlined the manner in which Bali was killed. Bali was a king whose subjects were described as happy with his rule. Periyar, father of the Dravidian movement, wrote the “True Ramayana” which highlighted these aspects of Rama. Periyar opposed the caste and gender-based discrimination that is inherent in the most popular versions of the Ramayana. According to Periyar, the story of the Ramayana was a thinly-disguised historical account of how caste ridden, Sanskritic, upper caste North Indian Rama subjugated South Indians. He identifies Ravana as the monarch of ancient Dravidians. Ravana abducted Sita, Rama’s wife in the epic, primarily as revenge against the mutilation and humiliation of his sister Shurpanakha. In his interpretation Ravana is a practitioner of Bhakti and a virtuous man.

In 1993, after the demolition of the Babri mosque an exhibition was mounted by the Safdar Hashmi Memorial Trust or SAHMAT in Pune, but it was vandalised. The apparent trigger was a panel which was displayed in the exhibition which showed the Buddhist Jataka version of the mythology. In it, Rama and Sita are depicted as brother and sister. In this version they belonged to an upper caste clan which to maintain caste purity did not marry outside the clan. Just a few years ago, ABVP, the student wing of the RSS, had campaigned for withdrawal of AK Ramanujan’s essay, “Three hundred Ramayans and Five Examples”. The essay showed how there are many versions of the Ramayana and most of them differ as far as geographical and other details are concerned.

HD Sankalia, a Sanskrit scholar and pioneer of excavation archaeology, had said that even the places like Ayodhya and Lanka may be different than what is understood today. He had argued that Lanka in the epic may have been located in Madhya Pradesh, for the sage Valmiki, to whom one of the most popular versions of the Ramayana is ascribed, did not seem to have been familiar with the vast region that exists south of the Vindhyas. Legend has it that the name of the island known as Sri Lanka today was known as Tamraparni. Besides, the Ramayana’s diverse narratives are prevalent not just in India but all of South East Asia. Paula Richman’s 1991 book, “Many Ramayanas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia” provides a glimpse of some of these versions of Rama’s story.

Richman writes, “While upper caste men in Andhra associate the Ramayana with the Sanskrit text attributed to the legendary Valmiki, the Andhra Brahmin women do not view Valmiki as authoritative. Valmiki appears in their songs as a person who was involved in the events of Sita’s and Rama’s lives and who composed an account of those events—but not necessarily the correct account. Like most of the participants in the tradition, these women believe the Ramayana to be fact and not fiction, and its many different versions are precisely in keeping with this belief. Contrary to the usual opinion, it is fiction that has only one version; a factual event will inevitably have various versions, depending on the attitude, point of view, intent, and social position of the teller.”

The Ramayana songs put together by Marxist literary critic Ranganayakamma, the author of Ramayana Vishavruksham, has women’s concerns as the central theme. The songs in this version present Sita as victorious over Rama and in them Shurpanakha gets to exact her revenge over Rama. Therefore, Ramayana exists in many more versions than the one that shapes the dominant narrative in India today. The version we see and hear of today takes off from Valmiki through Goswami Tulsidas, but it is popularly understood largely through the televised version propagated by Ramanand Sagar. This version was telecast yet again during the Covid-19 epidemic. In addition, Rama’s story has been translated in Balinese, Bengali, Kashmiri, Thai, Sinhala, Santhali Tamil, Tibetan and Pali and numerous other languages including multiple English and other versions.

It would disappoint those pursuing the Rama temple construction that none of these narratives match each other exactly. Thailand’s Ramkirti or Ramkin does not portray Hanuman, contrary to the dominant Indian narrative, as a celibate. In Jaina and Buddhist versions of the Ramayana, Rama is a follower respectively of Mahavira and Gautam Buddha. In both these versions Ravana is presented as a great sage with vast resources of knowledge.

Some versions of the Ramayana that are popular abroad show Sita as a daughter of Ravana. Even in India, the Malayalam poet Vayalar Ramavarma’s poem, Ravanaputri (Ravan’s daughter) is famous. Many versions show that Dasaratha was a king of Varanasi, not Ayodhya.

The rich diversity of these narrations shows the prevalence of the Rama story in South and South East Asia. The Rama temple movement in India was constructed around a single narrative which has the lineage of Valmiki, Tulsidas and Ramanand Sagar. Even these three have subtle differences. The present dominant narrative upholds the caste and gender hierarchy, which is the core agenda of communal politics. Emotions have been generated around this and there are repeated attacks against those who interpret this mythology as different from the one suited to communalists.

Scholarly works on the Ramayana reflect the diverse values that prevailed at the time of their writing. Every nationalism constructs its own narrative of the past. Eric Hobswam said that history is to nationalism what poppy is to an opium addict. It would seem that nationalism also selects a mythology which suits its agenda.

The author is a social activist and commentator. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.