Gandhi Belongs to the Nation, Every Indian is Tied to his Legacy

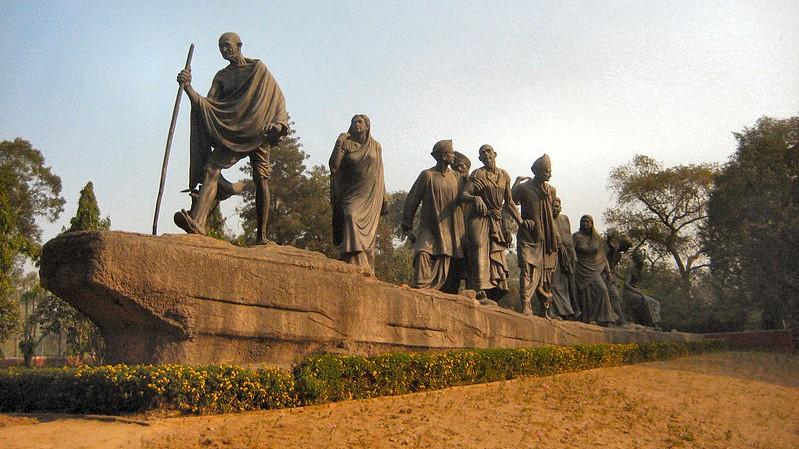

Gyarah Murti statue, commemorates the Dandi march (1930), New Delhi. | Image courtesy: Wikipedia Commons

MK Gandhi changed all who came in touch with him. The renowned writer Mulk Raj Anand once told me he visited Sabarmati Ashram in Gujarat to meet Gandhi and seek his permission to live there. That was when he had finished writing The Untouchable, which 19 publishers had turned down. Anand said, “I had suffered a nervous breakdown for the second time. In that condition, I travelled to his ashram. Gandhiji allowed me to stay on three conditions—never to look at a woman with desire, never to drink liquor, and to clean the toilets.”

Mulk told me he accepted the three vows but became friendly with an American lady typist living at the ashram. When Gandhi found out, he asked Anand to leave. “I was not in a relationship with the American woman. We were friends. She was a single divorced mother, so I would look after her baby while she worked. But other ashram residents carried tales to Gandhiji, and he asked me to pack my bags. I had to leave but continued meeting Gandhiji, for he had saved me from destruction,” Anand told me.

Gandhi advised Anand to take train journeys across the country to understand its people. “I changed after seeing the real India,” Anand told me. He never forgot Gandhi’s talisman: Whenever in doubt or when the self becomes too strong, recall the poorest, most helpless man you may have seen and ask yourself if the step you contemplate will help him.

Aligarh-based academic-parliamentarian Prof Jamal Khwaja and his spouse Hameeda Durreshahwar Akbar told me they were swept up by Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru’s call for communal amity in the ’50s. Jamal Khwaja’s father, Abdul Majeed Khwaja, was a close associate of Gandhi’s. In 1920, Gandhi stayed in their ancestral family home in Aligarh. Hameeda told me she and her husband broke traditional naming conventions for building a secular India. They gave their four children a combination of Hindu and Muslim names: Jawahar Kabir, Gita Anjum, Rajan Habib, and Nassir Navin.

I often met the children of Gandhi’s youngest son, Devadas Gandhi. Ramchandra, Rajmohan, Gopalkrishna and Tara Bhattacharjee Gandhi followed in their father and grandfather’s footsteps in their unique ways. Gopalkrishna Gandhi was a very young child when Gandhi passed away, but his connection with his grandparents was intensely emotional. The late Ramchandra Gandhi lived frugally, like Gandhi.

Tara Gandhi Bhattacharjee was 13 when Gandhi passed away, and she never let go of his legacy. Years back, I met her at her home in Delhi where Gandhi’s spinning wheels or charkhas, hand-made dolls, and hand-spun khadi were ubiquitous. She wore khadi all year round, which she spun at home. The lounge was her mukt or free room, where she could do what she liked, read, nap, make dolls or spin thread.

When I asked if she had any memories of Bapu, she paused working the takli and said, “I remember I had a lot of homework to do that day. Initially, I couldn’t believe it had happened. Slowly, it became clear. I could sense the entire nation was with him. People kept coming in and out of our house. Unlike today, leaders and politicians moved about freely those days, without security guards or bandobast.”

Nostalgically, she told me, “Though most of my childhood was spent with Bapu and Ba [Kasturba Gandhi], he kept a very tight schedule, so I saw little of him. In our conversations, he stuck to mulya or basic issues like the value of time or how we must use postcards for correspondence as it saves paper and ensures there are no secrets! He showed us how to lead a clean life aesthetically. His sense of aesthetics was so strong that the sophisticated Rajkumari Amrit Kaur felt at home in our house. Even when I close my eyes today, the images of our home at Birla Ashram come alive. I can hear my mother and Bapu talking. I never saw him angry or cranky. But, yes, he often looked sad. When upset, he would stop talking, keep a maun or roza and stop eating. He would sit at the charkha, spinning.”

Do she or her brothers feel inclined to claim Bapu’s belongings in various ashrams which, news reports would say, are not kept in the best condition? She told me those items “belong to the nation, and if they are not being looked after, it just shows the decay of our times”. She said she inherited just one item from her grandfather: a small wooden box her father, Devadas Gandhi, got as a wedding gift from Gandhi.

During our first interaction in 1994, Tara told me she kept away from politics because she did not want to put any party above her country. “Today, politics is more of a cleverness drive. How can I even think of joining a party when I don’t meet politicians, especially those in power?” she said.

Rajmohan Gandhi told me once during an interview that he does remember Gandhi and the day of his assassination. “I was enrolled in the Modern School on Barakhamba Road in New Delhi. Due to a function, I left school only at 5 pm that day. Our home was close by, as my father was the editor of The Hindustan Times, and we lived in an apartment in the Bombay Life Insurance Building on Kasturba Gandhi Marg. That day, I saw my father’s secretary, Kali Prasad, standing at the foot of the building. He immediately took me to the Birla House, where I learned that Gandhiji was no more.”

From September 1947 to January 1948, Gandhi lived in Delhi, though not with Rajmohan’s family. “But we met him every single day,” he told me, adding, “We had a close bond with him but not a leisurely relationship. We did not have special rights to his time as grandchildren. He belonged to the entire nation. I did not understand this then, but later I understood that the family had to pay a heavy price to achieve the goal of freedom.”

Rajmohan said he always had an inkling of why they, his grandchildren, could not spend much time with Gandhi. “He was either in jail or travelling across the country, quenching communal fires. He would conduct daily multi-faith prayer meetings at 5 pm at the Birla House, which we children would attend to the end. Then we would go home and, after dinner and homework, spend about half an hour with him. During this time, we would sit and talk,” Rajmohan recounted.

Rajmohan told me he inherited a unique value system from his grandfather and father. “My father brought us up on the same values [as Gandhi], that money-making was not the purpose of life, that service was to be part of life. He emphasised that any service ought to be unconnected from personal advancement. He always stood for the freedom of the press,” he said.

Rajmohan also spoke about how Gandhi had adopted all of India as his family. “And we, his grandchildren, accepted that he was the father of this nation, so, as far as his legacy is concerned, every citizen has the same rights and responsibilities as we. We accepted this position very happily.”

The royalties from Gandhi’s books and publications don’t go to his family members, nor were Gandhi’s relatives the heirs to their ancestral home at Porbandar in Gujarat. Rajmohan said, “He is as much your grandfather as mine. He is not our property but your property. So it is the duty of all citizens of this nation to take care of his ashrams and institutions.”

I also asked Rajmohan why he did not re-enter active politics, apart from his stint with the Janata Dal that left him disillusioned and paved the way to remain in academics. He said, “Today, political parties have hardened their stance on questions of caste and religion. My inability to do that prevents me from finding a strong voice in any political party. I still remember that when I joined politics, I used to get special invitations for [events like] ‘bania sammelans’. People used to come to me and say, ‘you are a bania, so you must attend.’ Until then, believe me, I didn’t even know I was a bania!”

The author is an independent journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.