How Ayodhya Ruling Made India a Sore Thumb of Mature Democracies

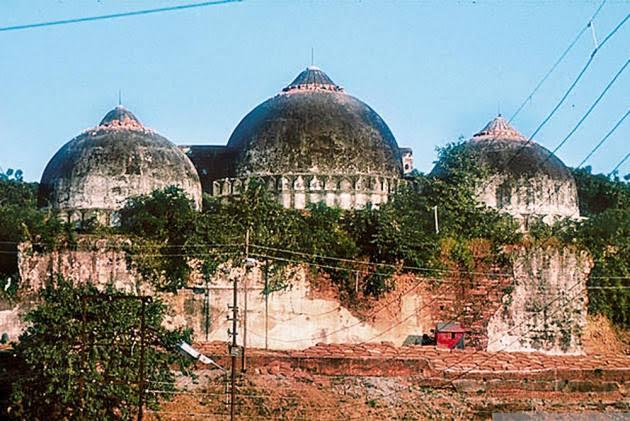

When India’s Supreme Court made the decision to rule in favour of the majoritarian Hindu group with regard to the land where the Babri Masjid once stood, it was an unusual and regressive legal decision among all advanced democracies.

Claims and conflicts over sacred religious lands are neither new nor unique to India.

In 1492, Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue, but what he discovered, when he landed in the modern day island of Antilles, was not a ‘New World’ but one inhabited by millions of indigenous peoples whom he mistakenly referred to as the ‘Indies’ or Indians. Living in villages, bands and confederacies ‘Indian’ territories spanned the entire two continents of North and South Americas and the Caribbean Islands.

From that moment of contact to modern-day jurisprudence, land rights, management and ownership has been the most contentious issue between Native American tribes and Europeans, their descendants and new immigrants in settler colonies of the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, Brazil, Chile and the Caribbean islands. The most pressing legal question has been: whose land is this and how to ascertain ownership?

Originally, it was the “discovery doctrine” which had been used to give ownership of all the land to the European nation that ‘discovered’ the Americas. Most notably, the “discovery doctrine” was promulgated in the landmark United States Supreme Court case of Johnson v. M’Intosh(1823), followed by Cherokee Nation v Georgia (1831), in which it was decided that the government of the United States was the true owner of the land because it inherited that ownership from Britain, the “original discoverer.”

While the “discovery doctrine” has since been legally challenged, the fundamental principle of such a view of property ownership forever dispossessed native inhabitants.

When it came to sacred religious sites, through much of the 19th and 20th centuries, the United States government provided direct and indirect support to Christian missionaries who sought to ‘convert and civilize’ Native Americans. From the 1890s and through the 1930s, the government moved beyond promoting voluntary abandonment of tribal religions to affirmatively prohibiting the exercise of traditional religion.

The Bureau of India Affairs (a federal government entity established to manage native land and reservations), writes Native Hawai’ian lawyer Makalika Naholowaʻa, outlawed the “sun dance and all other similar dances and so-called religious ceremonies as well as the usual practices of so-called medicine men.” It was not until 1934 that the United States government fully recognised the right of worship on Native American reservations.

Along with the free right to worship, what came to the fore was the sticky matter of lands which were known to be sacred to traditional Native American religions; many of those sites were on federal government land. It was not until 1970 that President Richard Nixon signed the first of its kind legislation returning 48,000 acres of the sacred Blue Lake land in New Mexico, which had been annexed by the United States in 1906, to the Taos Pueblo natives.

Another example of a successful defence of a sacred site involved Kootenai Fall in Montana, which was threatened by a proposed hydroelectric development in the 1970s.

In 1988, the United States Supreme Court, for the first time, directly considered the issue of protection of sacred religious sites in the case of Lyng vs Northwest Indian Cemetery Protection Association. The case involved the construction of a road by the Forest Service in Northern California which the government asserted would improve access to timber and recreational resources. This area, also known as the High Country, was used by the Yurok, Karuk and Tolowa tribes as a religious site. The Supreme Court ruled that the negative impact upon the traditional Native American religious practices outweighed the government’s interest in building the road.

Since then there has been a growing realisation of the wrongheaded approach of the “discovery doctrine.” In the past 40 years, almost all such laws in advanced democracies focused on the protection of sacred religious spaces, not to annihilate them. The most prominent was Canada’s Nunavut Land Claim Agreement of 1993, an agreement which gave the aboriginal Inuit people a separate territory. Among the broad range of political and environmental rights included in the agreement was management of heritage Inuit religious sites. New Zealand began to recognize religious land claims of the indigenous Maori people in the 1980s and have formed tribunals to resolve such claims.

When Captain Cook planted a British flag on Australia’s east coast in 1770, he declared the entire country as terra nullius or “belonging to no one.” In 1992 terra nullius was invalidated by the High Court of Australia which recognized the First Australians’ right to reclaim their lands, especially for worship and agricultural use.

The Ayodhya verdict is the radical opposite of evolving laws in many such advanced democracies where the push has been to protect sacred religious sites and accommodate minority religious practices. This verdict, on the other hand, advocates the recognisably dubious primal claims by agents of a majority religion.

The verdict is also worse than legal decisions like the ones we have seen in the United States, Canada and Australia where economic reasons were often invoked—such as development, mining or tourism—to occupy sacred sites.

The Ayodhya verdict applied a faith-based reasoning to assert pure religious majoritarianism, with no inherent value for the society at large. Building another temple, in a country replete with temples, can neither be an economic necessity nor of compelling public interest.

The verdict is inherently regressive in that it moves the country’s laws towards religiously dogmatic claims. Ironically, it also brings India closer to Saudi Arabia, an authoritarian state stuck in medieval times, where faith-based laws of sharia trump minority rights, justice and fairness. Similarly, it emulates the exclusionary and majoritarian “discovery doctrine” advocated by 18th-century European colonisers rather than laws of today’s modern and advanced democracies.

India’s Supreme Court helped Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 21st century India leapfrog—backwards.

Shakuntala Rao teaches at the Department of Communication Studies, State University of New York, Plattsburgh. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.