India’s Fall From Ambedkar Jal Satyagraha to Indra Meghwal

Image Courtesy: SabrangIndia

Indra Meghwal, a nine-year-old third standard student of a Saraswati Vidya Mandir at Jalore in Rajasthan, was beaten by his teacher on 20 July. This boy’s “crime” was drinking water from a vessel apparently ‘reserved’ for his teacher, an upper caste male. This is how Indra’s parents and classmates have depicted the events that led to his death after a futile search for medical care. Now has begun their struggle for justice, for another interpretation of the day’s events is that Indra was beaten after a tiff with a schoolmate. Whatever the case, the boy died after he was beaten, and at a time of increasing caste atrocities. Reports of the segregation of students and discrimination based on primordial identity are certainly not rare.

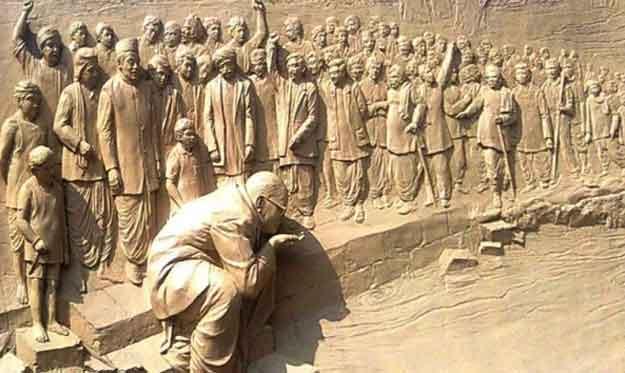

In India’s recent history, which we have been recalling as part of the celebrations of 75 years of independence, the movements to eradicate untouchability and for universal access to public drinking water sources ran side by side. Both movements travelled far, passing through many unique phases. The travails of Mahatma Jotirao Phule revolved around facilitating access to education for Dalit children, which Hindu scriptures expressly forbid. Ambedkar stood tall among all social reformers who strove for material justice for the oppressed classes. On 4 August 1923, the Bombay Legislative Council opened state-funded schools, watering sources, dharamshalas, courts and dispensaries to the former ‘untouchables’.

After the historic decision, on 19 March 1927, Ambedkar marched to the Mahad Chavdar Talab, a water tank, to drink water with a large group of supporters. The party was thrashed, and the tank was “purified” by the members of elite castes who opposed them. Yet Ambedkar’s movement caught on, and people became aware of the discrimination against Dalits. In 1930, Ambedkar sought entry to the Kalaram temple in Nashik, again confronting strong opposition from the elite castes. By 1930, the situation was even more challenging as the Hindu Mahasabha had come into being, as had, in 1925, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh or RSS. It is noteworthy that neither organisation supported Ambedkar’s struggle for equality, though Mahatma Gandhi did take up the cause of eradicating untouchability in 1933.

In due course, the RSS’s second chief or sarsanghchalak, MS Golwalkar, openly upheld the Varna caste system in his book, “We or Our Nationhood Defined”. So did Deendayal Upadhyay, another prominent Hindutva ideologue, whose idea of ‘Integral Humanism’ supports caste hierarchies. Indeed, the struggle to eradicate the barbaric practice of untouchability and exclusion of the Dalits began from Ambedkar onwards, but its pace has been painfully slow. The Jalore tragedy represents the starkest form of this sluggishness to reform.

Atrocities against the Dalits hold a mirror to society. They prove that despite decades of effort, discrimination and exclusion continue, even in their most severe form. Despite stringent laws, practices humiliating to the Dalits persist in India, and they travel abroad with non-resident Indians. The anti-Dalit atrocities laws are very apt, but evidently not effective. After incidents like Jalore, they appear to exist only on paper. The data compiled by Ashok Bharti, chairperson of the National Confederation of Dalit and Adivasi Organisations (NACDOR), based on figures gathered from the annual reports of the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) from 1991 to 2020, show there were more than seven lakh atrocities on Dalits over these years. Around 38,000 Dalit women have been raped in the last two decades. More than five atrocities per hour occurred against Dalits during the previous five years. It is, therefore, apt to ask if law enforcement is working as it should.

It is also important that the emphasis on “our culture”, which is the hallmark of right-wing politics, must be questioned afresh. Culture, indeed, is a precious aspect of human existence. But what part of a culture we adopt is essential to the outcome we receive. Are we choosing to follow Buddha and Kabir from our culture, who spoke of substantive equality? Or are we choosing to follow the culture represented the school young Indra studied in? In his school he allegedly faced the wrath of a teacher, who is also a caste elite.

The practices in the Vidya Bharati's chain of schools—their imposing a culture of Brahmanism on young students—also need to be questioned. Why are the values of Bhakti saints and social reformers such as Jotirao Phule and Ambedkar not taught instead of the so-called ‘values’ these schools are imparting? In fact, Phule and Ambedkar struggled all their lives against Brahmanical oppression. It is a question what, if at all, is said about these figures and about Gandhi, in these schools. Gandhi opposed the heinous practice of untouchability, which stands outlawed in India and yet persists, and proposed India as a mosaic of religious and regional identities. Indeed, the influence of Ambedkar made Gandhi give fighting the Varna or caste-based inequalities and untouchability due importance.

Multiple aspects of the Jalore tragedy are being highlighted, but what is ignored is that the school belongs in the Saraswati Vidya Mandir network, a large and growing organisation that has spread deep inside India’s schooling system. They claim to focus on shiksha or education and imparting sanskars, which is more challenging to translate. Roughly speaking, sanskar means ordination. In the Indian context, it is another name for instilling Brahmanical norms.

Vidya Bharati has run the Sarswati Vidya Mandir chain of schools since 1952. During the Janata Party’s rule, the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the previous avatar of the BJP, was part of the ruling combine. BJP leaders such as Atal Bihari Vajpayee and LK Advani were in the ministry, and Vidya Bharati became a formal organisation around that time, in 1977-78. By entering the formal education sector, it got an opportunity to propagate its norms and instil them in students. Today, are these schools silently working to uphold values from a mythical golden past and stress caste and gender hierarchies? They already account for 2% of schools in India.

Vidya Bharati incorrectly proclaims that every developed nation prioritises educating its children in faith and culture, while India, the “land of Dharma” has the misfortune of having no such arrangement. Contradictory social trends mire the present situation. On the one hand, excellent lip service is paid to Ambedkar’s thoughts and values. On the other, chains like the Vidya Bharati’s schools focus on sanskaras, which have deep roots in Varna, jati, and therefore, untouchability.

We do not know whether the Jalore tragedy is a one-off case in such schools or if there is a pattern behind it. However, the teacher who beat the child was responsible for spreading the sanskaras of the organisation among the enrolled students. We all know, the RSS has been trying to woo non-elite communities within the Hindutva fold. Indeed, they have gained some success. However, incidents like in Jalore remind us of the deep rot in such institutions. We must introspect why Indra had to die and change our schooling pattern to ensure accountability, and that those who have suffered for centuries are never again tormented.

The author is a human rights activist and formerly taught at IIT Bombay. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.