Indian State, Maoists and Tribals

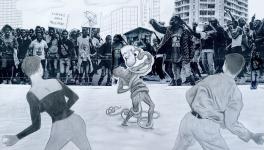

Image Courtesy: DefenceTalk

What the Union Home Minister Amit Shah said soon after the recent incident in Bijapur that claimed the lives of 22 jawans is nothing new. To “intensify the fight against the Maoists” can only mean more violence and the use of force in a more coordinated manner. It could also mean better coordination between the states where Maoists are active and a more proactive role for the Centre, not leaving matters to the states.

Further, it could mean moving from the CRPF and BSF to a specialised task force, such as the Greyhounds in Andhra Pradesh, supplemented by the Army and Air Force. Finally, it could mean treating the Maoist threat as a full-fledged civil war and open the way to traditional warfare, even aerial bombing, which goes way beyond the current combing operations.

It is well within the legal powers of the Indian government to use force against an armed group that questions state sovereignty. Maoists do have trained squads and advanced weaponry. However, the problem is how to fight them without causing “collateral” damage. Armed combat with Maoist militia would involve a high possibility of collateral damage to the local civilian/tribal population.

The fact that an overwhelming majority of tribals actively or tacitly support the Maoists compounds the problem. One cannot “wipe” out the Maoists without in one way or another “targeting” the local tribal population. That is what routinely happens in the course of combing operations. The security forces, either compelled by strategic reasons or by actively committing excesses, also target the local populations. One of the most notorious counter-insurgency operations unfolded under previous Home Minister P Chidambaram. It went by the name Operation Green Hunt, and as part of it the state invented Salwa Judum, a private militia. It unleashed wanton violence against the tribals, forcing them to flee their villages and seek refuge in government-run camps.

Evidence shows that all of these strategies, which justify collateral damage, increase the Maoist recruitment manifold. The use of reckless violence also increases support for Maoism. However, what initially draws tribals to the Maoists is the threat of eviction from their lands, in which the government and corporate sector wish to access mineral reserves. The assessment is that mineral resources running into thousands of crores are at stake in the tribal belts.

Again, previous political regimes used their Eminent Domain to legitimise mining in the “national interest”. It raises questions about the model of development pursued by the state and whether tribals will have a say in permitting or refusing extractive processes. Forest officials and non-tribals routinely exploit natural resources in tribal areas, which only adds to the difficulties of the security forces involved in combing operations. Without local support from the tribals, they will be unable to win this “war” against the Maoists.

Some well-meaning human rights groups suggest treating Maoism as a socio-economic problem and not an exclusive law-and-order matter. It needs recognition that Maoist groups mobilise tribal support politically, not through coercion and fear. Therefore, some rights groups and activists suggest “peace talks” as a way out of the vicious cycle of violence. They also ask for political means to address governance in tribal areas, the development model, and other concerns. The Committee of Concerned Citizens (better known as CCC) attempted to hold peace talks between the Andhra Pradesh government and the Maoists in 2004, though they failed to fructify into anything concrete.

The Indian state has always felt that peace talks are a ruse for the Maoists to regroup and get some respite when they have grown weak. It also believes that civil rights activists aid and abet the Maoists by bringing up peace talks. For this reason, the current regime has left no stone unturned to target such voices by branding them as Urban Naxals. Would the Indian state stand to gain by targeting and delegitimising the voices that support human rights, which can still help engage with the Maoists and reduce the spiral of violence?

Indian state policy on the Maoist problem has nothing fresh to offer—just more scaling up of violence and accompanying problems, as listed above. It also needs to be mentioned that the Maoists and their insurrectionary tactics have escalated the violent spiral. Maoists use advanced weaponry now and have a growing dependence on violence—as against political mobilisation. It has severely limited their reach and also creativity. Partly, the over-emphasis on violence flows from the Maoist philosophy that power flows from the barrel of a gun. Partly, it flows from the Leninist centrality of State power.

Any political movement that assumes overthrow is a legitimate route to power—for whatever purpose—can never be seen by the larger society as a moral force. The singular emphasis on the overthrow of the state has hampered the creative potential of the Maoists. It is why they gradually lose the support of various sections of society. They now have to depend on the most dispossessed for their support and to justify their means. It is yet another vicious cycle internal to the Maoist political imagination.

The ongoing farmer movement has demonstrated that non-violent means still work. They have also shown how sustaining mass mobilisations requires movements to internalise several other micro-struggles—including jostling with caste and gender prejudices. India is a complex and diverse society that needs innovative methods—not a mechanical repetition of ideas on class struggle. While the Indian state refuses to think, the Maoists refuse to rethink their political strategy. That is why there is a prolonged stalemate and unwarranted loss of lives. An overwhelming number of those who die are the very tribals and poor communities in whose name the stalemate continues on either side of the political divide.

The author is an associate professor at the Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.