Integrity via Harmony: The Cuban Boxing Philosophy That Shaped India

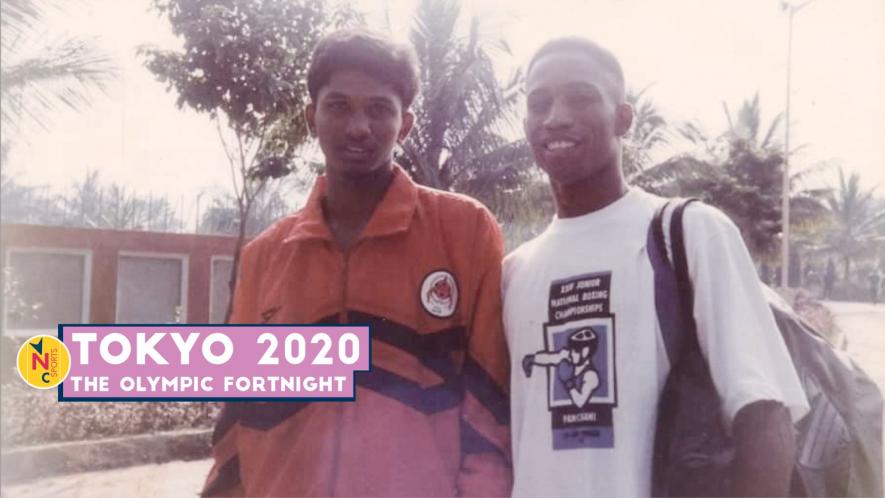

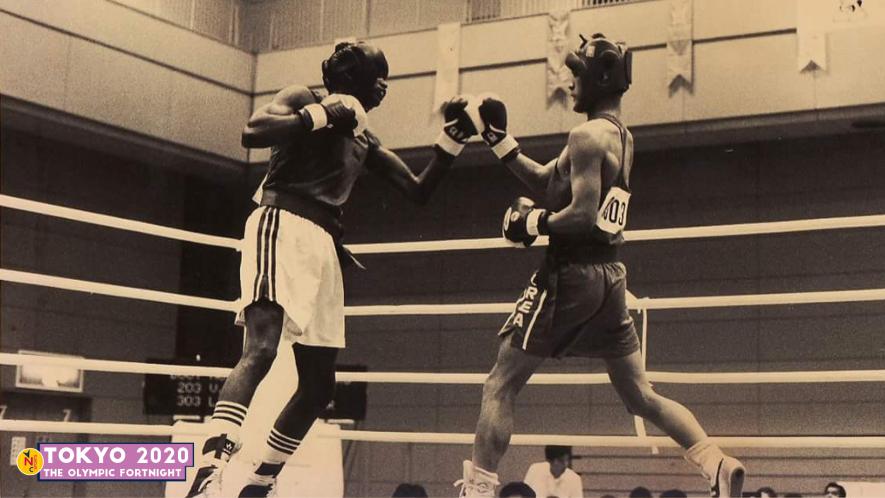

Devarajan (left), prepared for Enrique Carrion at the Olympics in ‘92, only to end up facing another Cuban who would go on to greatness, and inspire a change in the Indian’s approach to boxing. (Pictures courtesy: V Devarajan)

A week after celebrating his 19th birthday, the teenager was in tears, hunched in a corner in a backroom of a sports facility in Barcelona. From the dimly lit corridor, an elder gentleman walked in, flanked by a person he was familiar with, a person he trusted. The gentleman, exuding a stately persona, spoke chaste, quick Spanish, an unmistakable warmth in his tone. V Devarajan remembers the moment vividly, even after 18-odd years — a lifetime — later. The interaction was one of the high points of his boxing career, alongside a World Cup bronze and many memorable victories in the amateur ring.

On that day, the 28th of July, 1992, Devarajan lost his Olympic debut in the capital of Catalonia. He was shattered. His coach, BI Fernandez, had walked into his moment of solitary pain with the legendary Cuban coach, Alcides Sagarra Carón, who wanted to have a word with Devarajan. He had sensed a spark. He had seen promise while sitting in the corner of Devarajan’s opponent for the day, Joel Casamayor. The Cuban coach, whose resume boasts of countless Olympic gold medal winners, including the legendary Teofilo Stevenson and Felix Savon, knew a few things about talent and potential. Sagarra saw Olympic and World medals in Devarajan.

“That’s what he told me,” says Devarajan, jogging back his memory, which happens to be “an exercise similar to shadow boxing,” he adds.

“I did not understand what he was saying,” Devarajan, a sports officer now with the Indian Railways and a national selector says. “Then Fernandez translated it for me. Basically, he told me to not lose heart. He said I will win Olympic and World Championship medals in the future. He advised me to work towards that.”

Click | For more from ‘Tokyo 2020, The Olympic Fortnight’ series

Devarajan digresses thereafter following a prod from this side of the voice over an internet call. Shadow boxing and memory…

Shadow boxing is an art, Devarajan expresses. “And it is more a mental exercise than physical.”

But, of course. A boxer fights a perfect opponent while shadow boxing. He himself, jousting with his shadow — a bout he will never win, will never lose either. If only real bouts were similar, with victory and defeat defined as learning and nothing more. But bouts follow their own narrative of blood and bitterness. Devarajan bit that bitter pill in Barcelona.

“I was supposed to and was ready to face the original Cuban boxer who was set to fight in the bantamweight in Barcelona — Enrique Carrion (the 1989 world champion),” he recalls. “I had fought him at the Giraldo Cordova Cardin Memorial Tournament in Havana a year prior to the Games and though I had lost at the time, I was confident. Casamayor was an unknown. To make matters worse, he was southpaw too. We had a well contested bout though.”

It turned out to be his only tryst with the Olympics, ending at the hands of a Cuban, who went on to win the bantamweight gold that year. Casamayor — a junior world champion at the time — was younger than Devarajan. Casamayor took the pro plunge too, earning a world title for his effort, becoming less of a Cuban in the process.

What is a Cuban boxer? The conversation swerved. Every Indian now is possibly a Cuban, answers Devarajan.

******

The 1990s, a period of churn in India, brought about pole shifts in almost every walk of life. Sport was not left out either, with cricket taking the major chunk of the liberalised ecosystem, football taking a nibble, and the rest embarking on their long journeys towards… Well, towards where they are now — the sports ministry having withdrawn recognition of almost all the national federations following a court order, and the Indian Olympic Association fighting an internal war. On the playing field, a nation of 1.3 billion enters the biggest sporting spectacle in the world, the Olympics, with the realistic chance of winning one, two, or three medals at the most.

Also Read | Barefoot Reality: Indian Football’s First Wave of Modernisation a Repercussion of Helsinki Disaster

With the customary, and very necessary, presentation of reality of Indian sport out of the way, let us look at the change minus the political wranglings. The change in the past 30 years has been apparent, but rather slow in one and very important area — catching up with the rest of the world. We are yet to do so (barring a handful of Olympians and a couple of sports). Boxing has fared better. And it all began in and around the time of the Barcelona Olympics.

Devarajan’s career had just begun at that point. It blossomed a couple of years later — in 1994 — when he won a bronze medal at the World Cup. He had his own adventure in the pro circuit in England, a decision which was forced upon by the unprofessionalism shown by the national federation back in those days, he states. An injury to the knee curtailed his time in the ring.

Devarajan’s pugilistic persona — from the art of meditative shadow boxing, to the ring craft that earned him victories and praise from opponents and legendary coaches alike — has an indelible Cuban stamp on it. His career with the national team began a little before the start of BI Fernandez’ more than two decade long stint. Fernandez joined the Indian team in 1990. He still remains part of the country’s boxing narrative though not with the national set-up anymore.

And Deva was amongst the first to be schooled and mouled in the Cuban way. The five who qualified for Barcelona — Rajendra Prasad (Light Flyweight), Narendar Bisth Singh (Featherweight), Sandeep Gollen (Light-Welterweight), Devarajan (Bantamweight) and Dharmendra Yadav (Flyweight), formed India’s biggest ever boxing contingent at the Games at the time. It was just a start as we know now. The production line of boxers of international calibre began from there — from the likes of Dinko Singh, Gurchanran Singh, Vijender Singh, Akhil Kumar and Jitender Kumar up to the current crop, Indians have a reputation in the international ring.

Also Read | Tradition Meets Trial: A Clash to Define India’s Middleweight Contender For Tokyo

Devarajan’s loss to Casamayor — the 13-7 scoreline — would have been much closer had they been boxing now. The point scoring system was more subjective then, explains Devarajan. “And the judges could be very subjective,” he explains. “Not that it is drastically different now but the electronic systems have negated some of it. Back then, India did not have that kind of a reputation as a force to reckon with. So scoring for us was much more difficult as judges would not see our punches. You know how it works right. And it was all the more difficult if an Indian is fighting a potential medalist. That too in the first round.”

Devarajan may have a point here. When we go through the result, his scoreline happens to be the tightest in Casamayor’s journey to gold, which included two knockouts and a victory margin of more than six points. Deva was beaten by six points. Casamayor won the final by a margin of eight points. These are assumptions, of course, though with a bit of legitimacy as definite points won and lost are mentioned. Luck was missing in the mix.

“Luck of the draw is so much important in boxing,” says Devarajan. “Then again, as boxers, when we train, we do so with the aim to beat not just the opponent, but punch the luck factor out of the ring too. That’s the attitude, the mental sharpness, that BI Fernandez brought in. The Cuban Way.”

******

Punching your way out of insurmountable odds and finding the destiny is a narrative that defines Cuba as a nation, in fact. Boxing is just one part of the larger saga. Boxing is intrinsically woven into Cuban society, culture and politics too and so the Cuban style, or Cuban school of boxing is unique, though derived from the Soviet system of athletic training.

Rich with Afro-Caribbean culture and traditions of art and music, Cuban boxing has developed its own systems, strengths and even weaknesses, following its own rhythm. Cuban boxers dance.

Also Read | The Walk: An Olympian, a Worker and a Home Yet to be Defined

“My god their footwork,” exclaims Devarajan. “They are beautiful. Footwork is the hallmark of Cuban boxing. Not to mention the accuracy and speed. The intensity is also breathtaking, while if you are at the receiving end of a punch, you are surely to go breathless.”

A Cuban’s biggest weapon was his speed and accuracy and the relentless dance of pugilistic excellence. He, then, stamped his will primarily with two weapons — the straight right, landed after set up by a flurry of jabs. All of this was done drawing circles around the opponent with deft footwork. The other weapon was the left hook, led by jabs and feints. Devarajan picked up the straight right, and hook from Fernandez. He also picked up the dance.

“I was nothing when I joined the national camp as a 17-year-old,” he says. “I was getting beaten up, I had no idea what was happening or how to improve. Fernandez got me ready to face international opponents. He taught me everything that helped me towards the medals I won outside. He taught me to focus inside the ring too, and to be fearless. He built me up from scratch. And I can vouch now that his hand was there in shaping the destiny of many boxers since then.”

The Cuban way was methodically woven into an imperfect boxing system. Before Fernandez, there were Russian influences in Indian boxing as well. Both the systems have similar DNA but there are fundamental differences too. One is an evolved version of the other. The other prominent school of amateur boxing is the American way — the pro-inclined philosophy. With the kind of cultural hold America started to have in Indian society post the 1990s — predominantly US centric media narratives via cable and entertainment sources — Indian boxers could have made a tilt towards that side. But Cuba, the evolved version of Russia, remained.

Boxing pundits and historians have spoken about how an evolution of the Russian system was inevitable in Cuba. The attitude in the ring is similar for starters.

Also Read | A Larger Design: Ten Step History of Art at the Summer Olympics

“Both Russian style [followed mostly by the great Eastern European teams] and the Cuban system emphasis on being light and on your toes,” says Devarajan. “Commitment towards the bout, chasing victories as well as beauty is a common trait. Beyond that, where the digression happens is on the emphasis of flair vs that of efficiency in the Eastern Europeans.”

Of course, flair coupled with speed and accuracy leads to efficiency. The Cuban school banks on that, the Russian way is a direct quest for efficient means to knock the defense down. Americans are a little haphazard, believes Devarajan, and the reason perhaps is that the boxers are caught between amateurism and a constant desire to turn pro and make a mark there. They get caught between the two — the speed, sharpness and high intensity style which works like a charm in the amateur ring, and a craft revolving around power-endurance needed in the pro arena.

The Olympics are just a stepping stone for boxers from the US school of thought. A means not an end. It is the other way round for Cubans, and for Indians as well.

Perhaps that’s the reason why the Cuban system worked perfectly for us. India is a land of inefficient efficiency, though. So, the Cuban school evolved and took a new shape of its own, but the basic tenets remain. Our boxers from the late 1990s till now, have shown glimpses of flair, ring-smartness and a desire to stick to the amateur ranks despite avenues opening up.

Gurcharan Singh’s plunge or Vijender Singh’s marketed stint in the pro rings are mere aberrations. It happened late in their respective careers to have allowed them the luxury to unlearn, learn and evolve as prize fighters, believes Devarajan. “The larger quest has always been the Olympics, much like the Cuban ideal,” he adds.

There is one criticism which Cuba as a whole has faced — liberty of a sportsperson, be it a boxer, baseball player or anyone else — to turn and pursue a professional career. That liberty exists, though, and Devarajan, who has had multiple training and competition stints in Cuba has seen how it works there.

“They remain amateurs by choice,” says Devarajan. “I have seen the respect boxers command in Cuba. Their legends could walk in and meet Fidel Castro anytime they wanted.”

Boxing there is not just a way out towards a better paying job in the government set up. Boxing is a way into the idea of Cuban integrity and inclusiveness.

Also Read | Run for Your Life. Running is Life

The gloves are also an avenue to break the shackles — for the Cuban boy or girl picking them up or an Indian kid doing the same thousands of miles away. A few years back, in conversation, Fernandez explained how one of his challenges and focus was empowering the young boxer — hailing from poor backgrounds invariably — to break out from a timid and jittery mindset. It was about freeing oneself to pursue one’s potential without fearing prejudices they have faced in the past. Break free from the demons left inside.

In other words, it was about giving the boxer the freedom to pursue his potential, a fundamental right under threat in the country as we speak.

Boxing empowers an athlete with that freedom to express -- with brute force at times, with beauty as well. It is a dance. Devarajan concurs. “It is a dance we learnt from the Cubans,” he says. “And then made it our own.”

The hint was that we have evolved the Cuban system, adapting it into something that works for us as a nation. Most countries in the world who have come up in the last 20 years have done so, points out Devarajan. Cuban coaches are behind the boxing revolutions in many nations. The boxing ring is a much more equitable world now. It hints not at the decline of Cuban boxing, but the way it has allowed the rest to grow towards it, catch up with it, and fight on an equal footing. A dance among equals.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.