Manipur’s Rescued Meiteis Return to Shattered Dreams, Dimmed Hopes

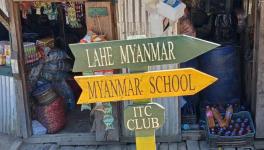

Imphal: On 3 May, 442 Meiteis fled across Manipur’s border with Myanmar to save themselves as the ethnic conflict that swept across the state reached their town, Moreh on the Indo-Myanmar border.

On 18 August, the Assam Rifles, which had been extracting them back to India in small batches, successfully returned the last lot of 212 with help from the Indian Army. Details of that hush-hush military-paramilitary operation, organised in the wee hours of Friday, are now beginning to emerge.

A senior Assam Rifles official says the rescue began after the Meiteis sheltered in Myanmar established contact in May. “We were bringing back people in small batches of 4, 6, and 8,” he says. In this way, around 200 people have been rescued since May.

But for the 18 August operation, a Quick Reaction Team (QRT) was set up, about which only a few senior armed forces officials knew. It consisted of the Indo-Myanmar Battalion—the Indian Army, and the Assam Rifles, which alone communicated with the Myanmar Army. “We had given word to them to look out for our people there. The Myanmar military looked after them despite a law and order crisis in their own country,” says the same official.

Those waiting to be rescued were on pins and needles, especially on the night of 17 August.

“On Thursday night, we were told to be prepared for our journey home. We jumped for joy and cried. I still can’t believe I am back,” says Thoiba, a 55-year-old among the rescued.

All of them are currently living at the Assam Rifles headquarters in Moreh.

Rescue Operation

“The Assam Rifles told us to cross all checkpoints and meet at a spot close to the border. Out of excitement, we reached early in the morning; some of us couldn’t sleep the entire night,” Thoiba says.

Neither did the handful of defence personnel selected for the operation. “We had to sanitise the area and ensure the route is safe,” says another Assam Rifles official. Both countries have a Free Movement Regime within 16 km of the international border.

At around 6 am, 13 people and by 11 am, a much large group of the Meiteis had gathered at the meeting point. Thoiba explains the mixed feelings they experienced—initially, we feared being attacked, then joy at being able to return and finally, dismay at the sight of burnt-down Moreh.

Many sensed on the drive back to Moreh from the border in military vans that the going would be rough.

The curfew in Moreh is relaxed only until noon. So, the rescue team waited for total curfew to kick in before it sprang into action. They placed 20 people in each bulletproof van and, with additional security, brought back the 89 women, 37 children, and 86 men. It took four trips. Indian Army teams received the Meiteis at the border gates with Assam Rifles and Gorkha Rifles commandants.

The drive from the Market Gate no 2 in Moreh to the Assam Rifles station was a fearful one. “I peeped out the small window, hoping to glimpse my house. The officer told me to keep my head down,” recollects Sang. He was among residents of Moreh’s Ward Number 4, the Premnagar locality, which took refuge in Myanmar’s Tamu area in the Sagaing Division.

Not everyone in the Assam Rifles knew of the operation. The QRT went radio silent for four hours on Friday. As it moved stealthily through once bustling Moreh, surrounded by burnt-down homes, any doubts they had about the challenging task dissipated.

The Army checked if those entering the vans were Indian citizens. “Most of us knew people by face as we have worked there for years. Verifying unfamiliar faces was the challenge. We wanted only Indian citizens to return,” says a member of the rescue team.

“Now on, it will be political decisions—we have executed our orders,” says the same team member.

Road Ahead

On paper, the options seem plentiful—transport the rescued Meiteis to Imphal, resettle them in Moreh or let them remain at the camp. For now, the Army is sharing rations and essential supplies with the 212 people. But the future is unpredictable.

“There was a lot of fear on the way back because of how we had to flee. We were worried about being attacked again,” says Rantham, one of the rescued Meiteis.

Before sunset on 18 August, word had spread in Kuki-dominated Moreh that the Meiteis were back. A senior official said several from the Kuki community gathered to protest—demanding separate administration.

“Even on Saturday, the situation in Moreh was volatile. While curfew in Imphal is relaxed till 6 pm, Moreh has stricter curfews as the tension in the border town has escalated since the return of the Meiteis,” an official says.

The Kuki Women Union for Human Rights said they would not allow the Meiteis to resettle in Moreh.

“Like we cannot live in Imphal any more, they cannot live here, we have separated,” says Chongboi Mate, who heads the organisation in Tengnoupal. The protesters insist the Meiteis must leave for Imphal, where the Valley has no Kukis since 3 May. “If they are not removed [from Moreh] within a few days, it will not be good,” she says.

The rescued Meiteis are caught between two warring sides—their own community and the Kukis.

Turmoil After Hardship

For Ninthumjam, 29, one of the three pregnant women among the 211 rescued, the Moreh she saw when she peeped from the window of her bulletproof rescue vehicle shattered her hopes of a fresh start. She spotted her home—except it wasn’t there any more. “There are two walls? That’s all?” she says over phone from Moreh.

According to a local administration official, in Moreh, no Meitei homes survived the violence. Mobs burned them on 3 May, on 28 May, during one of many escalations, and on 26 July, when homes were also robbed. At least 70 houses were burned and 30 vandalised.

The cycle of violence and revenge attacks has abated since May, but the social divide looks written in stone—no Meiteis allowed in Kuki areas, and vice versa.

But six months pregnant Ninthumjam’s immediate concern is finding a gynaecologist, as is Kumdra Devi, five months pregnant, and Nishi, eight months pregnant. “I was so worried. There was no medical facility. How would I give birth there, in the jungle?” says Ninthumjam, who scurried to Tamu on 3 May with her husband and mother.

Kundra’s joy on discovering her pregnancy was also short-lived. She sheltered in Myanmar, but her husband and daughter have been in Imphal since 3 May and they still cannot reunite. “I couldn’t speak to them regularly as we didn’t get [mobile] network. I had to walk closer to the border, which was risky,” she says.

It is Nishi and Sanalika’s first child. “My wife could not even run fast when we were fleeing. We were scared then and today—what if they attack again?” says Sanalika, over the phone from Moreh.

The biggest problem living in Myanmar was the lack of medicines. “I had Rs 6,000, which bought food and medicine for the first few days, but then it ran out,” Ninthumjam says. All her valuables were left behind—none of them had imagined they would be gone for months.

“I feared for my unborn child the most. I had not seen a doctor and had pain sometimes, but could do nothing. We had been praying for a child,” says Ninthumjam.

Across the border, everybody depended on the kindness of others once their resources went dry. “At times, I begged locals for medicine,” she says. “I have painful memories,” she says.

Her husband had a business in Moreh—the poor man’s Hong Kong, where electronics, kitchen items and clothings are cheap. Buying from Moreh and selling in Imphal was always a good trade. The family thrived and prayed hard for a child. Their good luck came after three years of marriage, but it was all swept away on 3 May.

In Myanmar, the 212 shared four toilets with no door or ceiling, just three tin walls. It was that or the endless forest. “We tied a cloth in the jungle and carried water to bathe,” Ninthumjam says. Everybody slept on the floor with no mattress or pillow—and three growing bellies.

One soap bar had to last among three for a month. “With no money, soap was a luxury, and the shop was far—one person would sneak out for essentials,” Kumdra says over the phone.

They ate rice for breakfast—just rice—irregular supplies dropped off by the military. “We were at the mercy of Myanmar,” says she. Lunch and dinner were also rice and dal.

“We got lucky if a local dropped off leftover vegetables. It was rare, but we felt thrilled on those days,” Kumdra says.

Several of the rescued say they hoped and prayed for rescue from those conditions, but the unrest that grips Manipur is as heartbreaking. They want to rebuild life in Moreh and for the government to restore peace. “But we can’t think of the future, for we have become homeless again,” says Thoiba.

The author is an independent journalist who has visited Manipur to report on the ongoing violence. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.