Relook at a Book: Victor Hugo’s Last Novel Influenced Several Revolutionaries

Bhagat Singh was a voracious reader of books that varied from political economy to literature. Though Victor Hugo was a world-famous classic writer of the 19th century, he is known more for his novel Les Misérables.

Hugo, who lived a rich and tumultuous life of 83 years, is considered one of the most respected writers of not only France but of Europe as a whole. The 19th century was an era of enlightenment in Europe after the French Revolution, giving rise to the slogan of ‘Equality, Fraternity and Liberty’, which later became part of the French Constitution.

Singh too had read Les Misérables and also discussed Hugo’s novel Ninety-Three with fellow revolutionary Sukhdev. Along with Leonid Andreyev’s novel Seven that were Hanged, their personalities as revolutionaries were shaped to some extent on the lives of revolutionaries in these two novels in France and Russia—at least these novels had left a deep impression on them.

For France, Hugo as a writer was one of the greatest. France gives more respect to its writers than its political leaders. As one of the most powerful French presidents Charles de Gaulle had famously said about Jean-Paul Sartre, “Sartre is France and I cannot arrest France.” Sartre had come on the roads to support France’s rebellious students in 1968.

Hugo wrote much in terms of quantity but is known for the quality of his works. Apart from the 10 books of fiction, he wrote more than 50 books, which include poetry, plays, prose and political writings. His other famous novel is Hunchback of the Notre Dame. He is considered the foremost writer of the Romanticism movement in literature.

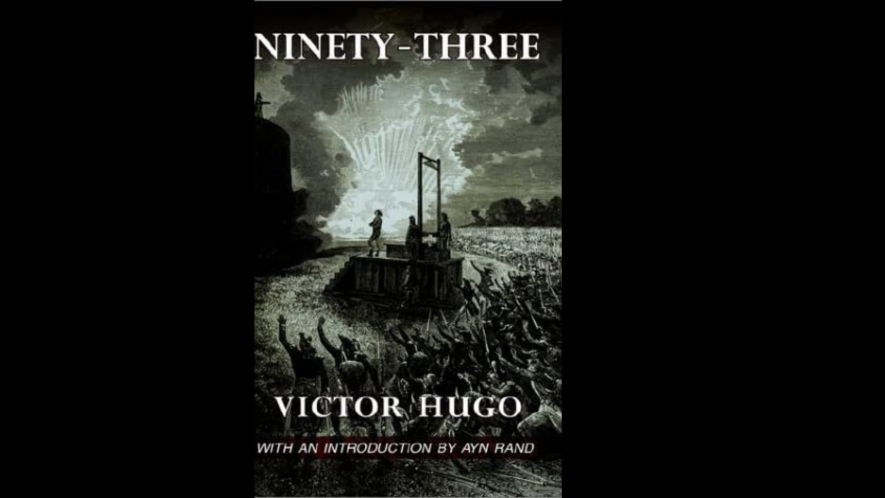

Ninety-Three was his last writing published in 1874 when he was 72. He died at the age of 83 in 1885. Hugo was also active in France’s political and revolutionary activities. He had become a member of the prestigious French Academy of Letters of France in 1841 and entered the Upper Chamber of Parliament in 1845 on the king’s nomination. Later, he was elected to the Second Republic’s National Assembly like the Lower Chamber in 1848 as a conservative. He broke from Conservatives in 1849 and became a votary of the abolition of the death sentence.

Hugo also spoke in favour of ending the misery of the poor and also supported universal suffrage. He was also in favour of free education for children. In 1851, when Napoleon III seized power, Hugo went into exile in 1855 and returned to France in 1870 after he was deposed.

Though like Charles Dickens in England, Hugo also initially supported the French colonialism of Africa as a ‘civilising mission’, he later became a strong votary of abolishing slavery in the Caribbean and decolonising Africa. He famously said in 1862, “Only one slave on Earth is enough to dishonour the freedom of all men. So, the abolition of slavery is, at this hour, the supreme goal of the thinkers.”

During the Paris Commune in France from March 18 to May 27, 1871, he was in Brussels, Hugo was critical of atrocities committed by ‘both sides.’ He freed himself from the impact of religion and declared himself to be a free thinker in the tradition of Voltaire, a progressive trend in those times. His rationalism offended some people and he faced slogans like ‘Burn Hugo’. Despite his many contradictions, he had become a hero for France by 1870. He was mourned as a national hero on his death. Several lanes and areas are in many cities of France are named after him.

The interesting part of Ninety-Three (Quatrevingt-treize) is that on one side, ‘Reds’ like Joseph Stalin and Singh had read and appreciated it, on the other side, ‘Whites’ like the iconic novelist of individualism Ayan Rand also admired it and even wrote an introduction to one of its English translations.

The plot is based on the French Revolution but was published three years after the Paris Commune. It is a long novel of nearly 350 pages with not very simple narration or storytelling.

Ninety-Three concerns the Revolt in the Vendée and Chouannerie—the counter-revolutionary revolts in 1793. Divided into three parts but not connected chronologically, each one tells a different story. The action mainly takes place in Brittany and Paris. The civil war in France had started in November 1792 and the murders committed were extremely gory.

The soldiers of the French Republic (Blues) encounter in the bocage Michelle Fléchard, a peasant woman, and her three young children fleeing from the conflict. When she mentions that her husband and parents were killed in the peasant revolt, the commander, Sergeant Radoub, convinces his troops to look after the family.

Meanwhile, a group of Royalist ‘Whites’ is planning to land the Marquis de Lantenac, a Breton aristocrat whose leadership could transform the rebellion, at sea. Suddenly, a sailor fails to secure his cannon and it rolls out of control and damages the ship. But the sailor risks his life to secure the cannon and save their ship. Though Lantenac awards the sailor a medal for his bravery but executes him without trial for failing in his duty. When their damaged corvette is spotted by ships of the Republic, Lantenac slips away in a boat with a supporter named Halmalo. The corvette distracts Republican ships by provoking a battle the damaged ship cannot win.

Lantenac is hunted by the Blues but is protected by a local beggar to whom he gave alms in the past. He meets up with his supporters and they immediately launch an attack on the Blues. Part of the troops with along with the family is captured. Lantenac orders them to be shot, including Fléchard, and takes her children with him as hostages. The beggar finds the bodies, discovers that Fléchard is still alive and nurses her back to health.

With Lantenac’s ruthless methods turning the revolt into a major threat to the Republic, leading figures of the Revolution Georges Jacques Danton, Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre and Jean-Paul Marat promulgate a decree that all rebels and anyone who helps them will be executed.

Cimourdain, who is a committed revolutionary, is asked to carry out the order in Brittany and watch Gauvain, the commander of the Republican troops there who is considered to be too lenient to the rebels because of his relation to Lantenac. The revolutionary leaders are unaware that Cimourdain was Gauvain’s childhood tutor and thinks of him as a son.

Meanwhile, Fléchard comes to know that her children are being held hostage in Lantenac’s castle. While fighting the besiegers at the castle, Sergeant Radoub spots the children. After persuading Gauvain to let him lead the assault, he manages to break through the defences and kill several rebels. However, Lantenac and a few survivors escape through a secret passage after setting fire to the building with Halmalo’s help. But Lantenac returns to rescue the trapped children after hearing Fléchard’s hysterical cries. Consumed with guilt, Lantenac gives himself up.

Knowing that Lantenac will be executed by a tribunal comprising Cimourdain, Radoub and Gauvain’s deputy Guéchamp, Gauvain visits him in prison. When Lantenac expresses his uncompromising conservative vision of society ordered by hierarchy, deference and duty, Gauvain insists that humane values are more important. To prove himself, he allows Lantenac to escape and then gives himself up to the tribunal.

Subsequently, Gauvain is tried for treason. Radoub acquits Gauvain considering his unfailing revolutionary record but Cimourdain and Guéchamp convict him. Later at night, Cimourdain goes to meet Gauvain before his execution the next morning. Gauvain outlines his own vision of a future society with minimal government, no taxes, technological progress and sexual equality.

The next morning when Gauvain is guillotined, a shot is heard. Cimourdain shoots himself with his pistol. The novel ends there.

Stalin, who had read the novel during his seminary in Georgia, was deeply impacted by Cimourdain’s character. During their discussion on the novel, Sukhdev had no sympathy for Cimourdain as he was against the very idea of suicide as a revolutionary. However, after being arrested and in jail, Sukhdev himself thought of suicide instead of spending his life behind bars. Sukhdev could not sustain a long hunger strike unlike Singh, BK Dutt and many other comrades.

The two letters exchanged between Singh and Sukhdev, one outside the jail and the second inside, throw light on the philosophical attitude towards the concepts of love and suicide. Singh was quite harsh in criticism of Sukhdev about the idea of committing suicide. Singh argued that revolutionaries had to remain prepared for prolonged suffering inside and outside the jail without ever thinking of suicide. Though he, like Stalin, understood Cimourdain’s dilemma, who could perform his duty as a revolutionary to get his ‘son’ convicted and guillotined but then out of paternal emotions shot himself dead.

The novel influenced a lot of Indian revolutionaries, who were fond of literature like their counterparts in other countries. Though not much discussed as a literary classic, Ninety-Three stands apart among its readership across the world. This keeps the novel’s socio-political relevance alive even nearly 150 years after its publication.

The novel has been digitised under Project Gutenberg and is available free on Internet archives.

The writer is a retired professor of JNU and an honorary adviser to the Bhagat Singh Archives and Resource Centre, Delhi.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.