‘Urban’ Vision in 2019 Manifestoes of Parties Leaves a Lot to be Desired

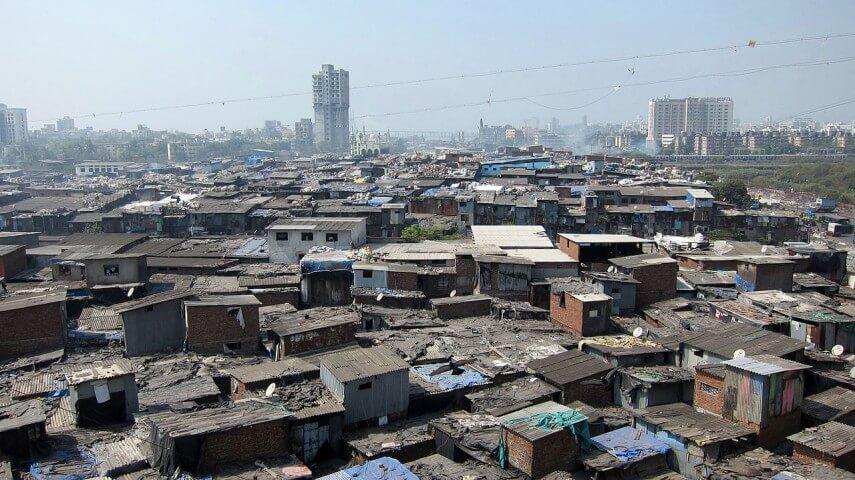

Image Courtesy: PropTiger

The 2019 election manifestoes of political parties have drawn a mixed reaction on the promises they are making for the Indian Cities. While some have been appreciative of the ‘right-sounding’ words for urbanisation in the manifesto of the opposition parties, others have been highly critical of the lack of imagination in the BJP’s poll declaration. This article presents another perspective on how the visible divergences in the manifestoes and the invisible convergences present a picture of what our cities and urban development can expect in the coming five years. And the picture is not exactly a rosy one.

The following are the key five takeaways for the ‘urban’ in the manifestoes:

1. The percolation of rights-based discourse and its internal contradictions

Agreeing with the popular perception that the manifesto drafting committees, especially, of the opposition parties have brought about a laudable change in the way cities and urbanisation is being imagined, a marked difference from the past has been the ‘rights-based’ approach to look at the issue of housing and slums.

Voicing the idea of “Right to Housing”, “stopping arbitrary evictions” and “slum upgradations” — the opposition parties have taken steps in the right direction, suggesting they were mindful of the unique challenges that we face in responding to the myriad urban challenges and urban communities. The specific mention of homeless — the ones who sleep rough, out in the open — in almost all the major political manifestoes is an indication that the urban has continued to capture the imagination in this election. And rightly so.

As a marked shift, the discourse on ‘Rights’ that has until now been restricted to access to services and amenities in cities, has positively nudged the focus for people-centric development paradigms.

Also read: Is India Committed to Empowering Its Cities and Their Inhabitants?

This rights-based approach to the urban — as somewhat visible in the Indian National Congress (INC) and especially more so in the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or CPI(M) — is in complete contradiction to the manifesto of the ruling party, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Devoid of people’s inputs and possible feedback loops, it reiterates the push for neoliberal, capital-led development of our cities — a model that has failed miserably in the past five years. ‘Housing (provision) to all, Water to all’ — remain promises that continue from the past. Without addressing the core concerns of inequity in our cities, these will remain promises to be repeated in the next election season. The Congress, too, here falls into the trap of ‘creating new cities and satellite towns’ and with an undue focus on ‘infrastructure development’ — ignoring the cries of the existing 10,000 and more urban centres. In the coming years, we can foretell an intensification of such fundamental challenges to our urban areas, where rights-based imaginations of the city will run into infrastructure-led missions, furthering contestations and struggles in the Urban.

2. The absence-presence of ‘smart cities’ and the obituary of urban governance in India

The biggest surprise of all the manifesto releases was the omission of ‘Smart Cities’ from the BJP manifesto. Five years ago, the dream of a hundred smart cities was sold to the populace and became a war cry for the elections, led by the assurance of ‘vikas’ (development). After no visible impact and possibly squandering of huge amounts of public money over ill-prioritised projects, the BJP manifesto chose to not even mention the Smart Cities Mission (SCM) — one of their hallmark urban schemes in the 2014 election manifesto. The omission of Smart Cities has led to many believing that the SCM will be rolled back by whoever comes to power this year. But while it’s worthwhile to celebrate that the government of the day is possibly rethinking the SCM, it will be opportune to look at the damage done to urban governance structures and the corruption of the discourse on people’s participation. Manifestoes until now, as a customary practice, carried the idea of decentralisation of urban governance as articulated in the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act (CAA). While the SCM demolished the existing governance structures through Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), what it has done is to mainstream the ideas of ‘special expert-led development’ of cities. Aside from the CPI(M), a well-known and vocal advocate of decentralisation, the other mainstream and national parties have conveniently chosen to overlook the irreparable damage to urban governance and employed similar SPV-like structures to dilute people-led development. Departing from Jan Bhagidari (people’s participation) in 2014, the BJP has given impetus to regional centres of excellence to support Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) and states.

In contrast, employing a more subtle language, the INC while claiming to strengthen the 74th Amendment, improving funding mechanisms and pushing for mayor-led city development, vouches for ‘separate administrative structure’ for each local body comprising experts and multidisciplinary teams. Thereby, altogether forgoing the real essence of 74th CAA — that of power to people, and decentralisation. In the years ahead, amidst the clamour of bigger and grander urban development, the urban governance and democratic spaces of engagement — and whatever remains of it — will also gradually recede. Such promises leave us with doubts about how inclusive the development would be. Remember Sabka Saath, Sabha Vikas (together with all, development for all)?

3. Walking in the City, or Cities with Metros?

The promise to improve public transportation and road connectivity usually finds mention in all pre-poll declarations — though often only to be forgotten later. Perhaps it is only on this topic in the manifestoes that there is an overwhelming consensus, over the need for strengthening public transportation and ensuring equitable access to the same, along with safety issues addressed. A special focus on gender, marginalised sections and people with disabilities was visible in all the documents. The focus on non-formal, non-motorized transportation modes with special attention to walking and cycling is also reassuring. Across the spectrum of parties, though the metro train is unequivocally preferred, there is visibly an unease on how metros will remain as a means of public transport without addressing the issues of affordability. It is debatable if a transportation policy, suggested in the BJP and INC manifestoes, will effectively address the public wastage of money on metros in smaller towns, under the alibi of modernisation of our cities. For example, the BJP manifesto intends to “ensure that 50 cities are covered with a strong metro network.” Such promises are bound to raise a lot of eyebrows as it is proven that there are other cheaper, easier and more public ways of addressing transport needs of Indian cities. The manifestoes were also mute about the contribution of transportation to air pollution in Indian cities. Moving ahead, it remains to be seen how we can ensure that the debate remains rooted to real public transport options and we do not end up espousing the increase of cars on Indian roads. The need is to strive to measure Indian cities with parameters of walkability and cycling, and more radically by the increased presence of walkable footpaths.

4. Increasing invisibilization of informal workers

Urban development cannot be seen as independent of informal workers who contribute as the majority workforce in cities. Having won the previous elections with the ‘chaiwala’ rhetoric, it is saddening to see that the BJP even failed to mention the plight of street vendors among other informal sector workers. Except for a one-line reference to increase of “minimum wages by 42 percent” and a passing mention of “pension scheme accessible to unorganised workers”, the BJP manifesto does not offer anything to informal workers. This, like other sections in BJP’s manifesto, is a far-shrunken version of the 2014 poll promise of labour codes, social security and welfare to workers.

Also read: Urban Poor Have Set Agenda for 2019 Elections

The INC’s manifesto as compared to BJP’s does well to include basic issues of identity, pension, access to healthcare and other entitlements. Also rightly stressing on skilling, supporting micro-enterprises, worker collectives, payment of minimum wages and freedom to associate. But there are glaring gaps concerning issues of correcting the minimum living wage and spelling out a need for Urban Livelihood Scheme, and there is no mention — leave alone any promise of repealing — of highly unpopular and anti-worker labour law reforms. Also, it is still a matter of shame that domestic workers continue to remain outside the ambit of manifestoes of all the major political parties, except the CPI(M). The leading Left party also had other progressive demands for enhancing workers’ social security. While it is relatively easy to debate on the issue of provision of identity and entitlements for workers, the real challenge lies in securing the place of workers in the city and its future imaginations. Some little promises like creches and working women’s hostels to increase women’s participation rate in Indian cities will go a long way in re-imagining the city for informal workers.

5. The lack of imagination for imminent climate change, disasters and environmental risks

It is a well-known fact that urbanisation is increasingly contributing to climate change. More so in India, with its progressively urban population expected to touch 50 per cent in 2030. The visible impact of this is the recurrent ‘urbanisation of disasters’ due to climate change over the past decade. The manifestoes across party lines, though perfunctorily acknowledging the existence of climate change, lack the imagination and futuristic vision required to address climate change and its intersection with the urban holistically. As a result, climate change as an issue has been pushed into the confines of the sections on ‘environment’ that approach the issue in a classical ‘protection’ of environment style. Such a treatment of climate change is fundamentally flawed on two counts.

First, protection of forests in ‘the Himalayas and Western Ghats’, however important they are, does not address the paradigm of urbanization currently prevalent that is obliterating ecologically sensitive areas — thereby neglecting the need to re-envision urban development with at least ecological conservation, if not expansion as its core focus. Second, the cities — which require to adapt to impending disasters and mitigate the impact for the future — need to prepare and strengthen themselves locally for the same. Climate change that is at present on the periphery of the urban agenda will in the coming years become the centre of the urban debate. The political manifestoes need to be refashioned in the coming years, accommodating the need to develop cities alongside the battle against climate change. And for that, thinking in silos will not result in radical paradigm shifts in how we urbanise in the coming decade.

To conclude, in aspects of housing and addressing the needs of marginal groups like informal settlements and homeless, the political manifestoes for the upcoming elections present a perceptible shift towards the right-based paradigm. However, the explicit lack of commitment to push for decentralisation of urban governance and envisioning informal workers as a central point in the urban is a matter of deep concern. Manifestoes are expected to be about how we wish to imagine and articulate our futures. The ones for the 2019 General Elections are devoid of that articulation. Small nudges will not make our cities radically different from what they are; what we require are fundamental shifts in re-imagining our cities as inclusive, sustainable and resilient. It is likely that such articulations need to emerge from the people and civil society themselves in the coming years.

Aravind Unni is an activist and urban researcher. Tikender Panwar is former deputy mayor of Shimla. Both are members of a civil society platform called National Coalition for Inclusive and Sustainable Urbanisation. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.