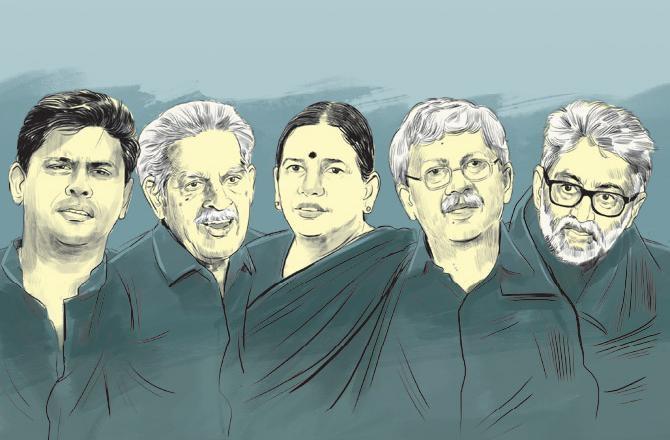

Why Allegations Against The Five Human Right Activists May Not Stick

Five Activists Accused in Bhima Koregaon Violence. (Image Courtesy: Mid-Day)

The Pune police has a lot on its plate. Apart from having to justify its actions to the Supreme Court this Thursday, they also have to justify their claims of uncovering an assassination plot. On August 31, the Additional Director General of Police Param Bir Singh read out from what was allegedly a letter plotting to procure arms and assassinate the Prime Minister. This was undoubtedly aimed at the public as it was beamed from major news channels. However, these alleged letters were never proved in Court, hence at present they do not mean anything. However, several decisions of the Supreme Court have suitably restricted the broad scope of offences against the State.

Also Read: Trial By Media: Pune Police Read Out 'Evidence' Not Yet Proved In Court

The provisions of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) invoked by the police are:

-

Section 16 – Punishment for terrorist act

-

Section 17 – Punishment for raising funds for terrorist act

-

Section 18 – Punishment for conspiracy

-

Section 20 – Punishment for being member of terrorist gang or organisation

-

Section 39 – Offences relating to support given to a terrorist organisation

Also Read: Arrests of Activists: Why Pune Police Is Aggressively Pursuing Tushar Damgude’s FIR

Considering the nature of the offences listed under the UAPA, it would be safe to presume that it was framed as an extension of Chapter VI of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC). This Chapter deals with offences against the State. The offences listed in this Chapter containing 12 sections range from waging war against the State (section 121) and sedition (section 124A) to offences by public servants relating to prisoners of war. The UAPA in contrast breaks down the general offences laid out in Chapter VI of the IPC.

Also See: Pune Police Commissioner Should Be Writing Crime Fantasy Novel: Ramchandra Guha on Arrests

However, if one were to consider the jurisprudence surrounding the provisions of law invoked in the present case, it would be clear that several important principles have been introduced to restrict the general application of these provisions. The landmark case that guided the jurisprudence of 'terror legislation' in the country was decided five years before the UAPA came into existence.

In Kedar Nath Singh v. State of Bihar, the Supreme Court was tasked with interpreting section 124A of the IPC (sedition) in the light of Article 19(1)(a) – right to freedom of speech and expression – and Article 19(2) – reasonable restrictions to Article 19(1)(a). The Court upheld the validity of the IPC provision after reading it down. In this regard Chief Justice Bhuvneshwar P Sinha stated:

“It is well settled that if certain provisions of law construed in one way would make them consistent with the Constitution, and another interpretation would render them unconstitutional, the Court would lean in favour of the former construction. The provisions of the sections read as a whole, along with the explanations, make it reasonably clear that the sections aim at rendering penal only such activities as would be intended, or have a tendency, to create disorder or disturbance of public peace by resort to violence.”

This view of the Supreme Court has been instrumental in balancing fundamental rights with penal legislations.

In 2011, within the space of two months, Justice Markandey Katju delivered three judgements. On January 3, Justice Katju delivered his judgement in the matter of State of Kerala v. Raneef, which was an appeal on a bail application. The applicant was a dentist who had been charged under the UAPA for treating a person who had attacked a university professor. The person was alleged to be a member of the Popular Front of India (PFI) and the dentist was charged with abetment as well as being a member of PFI.

On the issue of abetment, Justice Katju was of the opinion that a doctor under the Hippocratic oath cannot refuse treatment and thus, there is no reason to infer abetment. On the issue of membership, he stated:

“In the present case there is no evidence as yet to prove that the P.F.I. is a terrorist organization, and hence the respondent cannot be penalized merely for belonging to the P.F.I. Moreover, even assuming that the P.F.I. is an illegal organization, we have yet to consider whether all members of the organization can be automatically held to be guilty.”

Following this, he referred to decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States of America which held that mere membership is not sufficient to determine guilt. Hence, they discarded the idea of 'guilt by association'. This was reiterated in the two subsequent decisions in February in Arup Bhuyan v. State of Assam and Sri Indra Das v. State of Assam.

In Arup Bhuyan Justice Katju expanded on the rejection of guilt by association stating; “mere membership of a banned organisation will not make a person a criminal unless he resorts to violence or incites people to violence or creates public disorder by violence or incitement to violence.”

However, it was in the Indra Das case that Justice Katju referred to the approach of Chief Justice Sinha in Kedar Nath. Taking cue from the 1962 decision, Justice Katju stated; “we are of the opinion that the provisions in various statutes i.e. 3 (5) of TADA or Section 10 of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) which on their plain language make mere membership of a banned organization criminal have to be read down and we have to depart from the literal rule of interpretation in such cases, otherwise these provisions will become unconstitutional as violative of Articles 19 and 21 of the Constitution. It is true that ordinarily we should follow the literal rule of interpretation while construing a statutory provision, but if the literal interpretation makes the provision unconstitutional we can depart from it so that the provision becomes constitutional.”

Also Read: #MeTooUrbanNaxal: India's Answer to Modi Regime

Considering the existing jurisprudence, it is unlikely that any of the allegations against the five human rights activists will stick. The UAPA restricts bail by directing the Court to deny it if based on the case diary there is a prima facie case. However, if the five accused persons were not present at the Elgar Parishad meeting in Pune, it would be most unusual if they are allowed to be arrested.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.