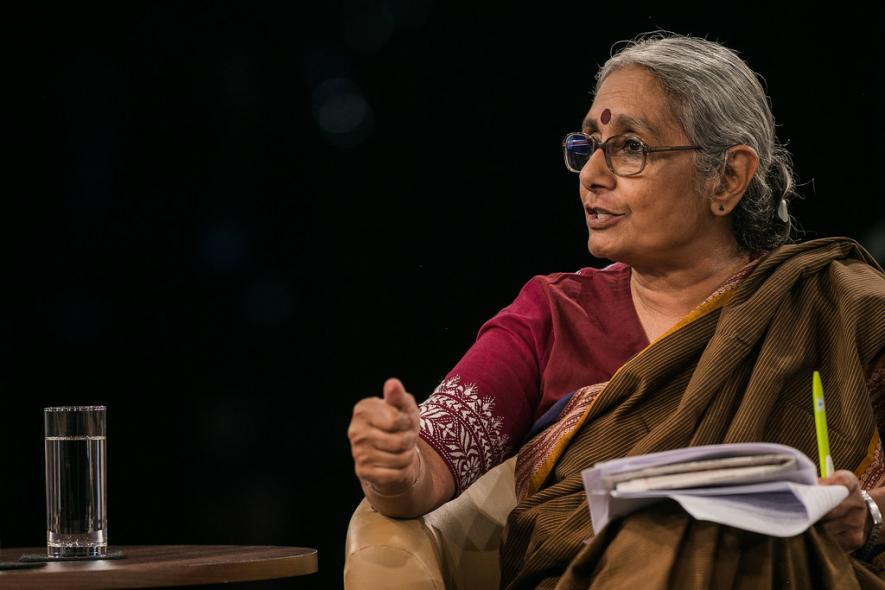

‘India Needs Inclusive Leadership that Brings People, Communities Together’—Aruna Roy

The driving force behind two landmark laws, the Right to Information (RTI) Act, 2005, and the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005, Aruna Roy is now witnessing the Modi government undermine both. In an interview with Rashme Sehgal, Roy talks about the need for democratic dissent. She says the unorganised sector workers will have a crucial role in voicing certain forms of dissent in the future. Edited excerpts.

You recently said in an interview that we in India “are losing” our right to protest. However, many who have raised a voice against the current dispensation face a slew of charges under stringent national security and anti-terrorism legislation. So, did you mean to say that we “have lost” our right to protest?

As long as the basic structure of the Indian Constitution is in place, we will have the fundamental rights of expression, dissent, and democratic protest. We might have a government that does not respect these rights and keeps undermining them as they are today. But suppression will only lead to more widespread protests, even at the cost of repressive consequences. That is the nature of democratic assertions.

The current dispensation takes strong exception to dissent and disagreement, especially claims to equality and secular rights. The right to freedom of expression is one of the most basic rights in our Constitution. The clever bearing down on this right and against protest locks all opposition away. Therefore, it is imperative for the status quo that any struggle for demands, including freedom of expression or personal choices regarding dress, food, and language, is silenced.

It is apparent not only in the denial of physical space to protest but also in the economic policies and imbalance in budgetary allocations that affect the poor. The right to assemble, and the right to fraternity, are equally threatened.

The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act and National Security Act are used to prevent religious and ethnic groups from building a discourse that questions the [denial of] equality guaranteed in the Constitution. Many governments have repeatedly used the Armed Forces Special Powers Act to quell democratic protest. These draconian laws enable state impunity and stifle voices questioning the denial of constitutional guarantees. That is why it is critical that all democratic protests and assertions come together to ensure the Constitution is protected and implemented in principle and process.

Statistics show an almost 95% increase rise in sedition cases since 2014. Journalists, students and trade union activists have been locked up, and the Chief Justice of India has questioned why such a law exists in independent India. How can people deal with this?

Application of the law of sedition has become another means to use state power to thwart inconvenient questioning or those who challenge the omissions and commissions of the government. The government often projects itself as the State. The range of people—from young students writing on social media to journalists, trade union activists and social activists—and the so-called seditious acts for which they have been picked up under this law make a mockery of its intent.

The law on sedition is colonial and should have been rescinded once India became an independent nation. The validity of such a law has been questioned by a cross-section of people, including members of the judiciary.

We have to start campaigning with political parties to build a public platform for citizens to come together to demand that laws that impinge on democratic rights be set aside or amended so that they are not used to stifle democracy.

For four decades, you have been at the forefront of movements, including the campaign for the right to information. How do you react to the Modi government steadily diluting the RTI Act, even though over eighty lakh people take recourse to it every year?

The RTI Act has been sought to be amended ever since it was passed. Six months after its passage, the UPA government attempted to amend it. The amendments were dropped because of huge public protests. The present dispensation has succeeded in making a frontal attack on the law by bulldozing amendments through Parliament, thereby diluting the law. Nevertheless, citizens who use the law are true democratic practitioners. They have understood that the RTI asks for the right to share power, which those in power are loath to do. This battle does not end with amendments to the law but continues every day through the 80 lakh people who use it.

Could you detail some of the recent amendments and how the government justifies them?

The amendments weaken the Information Commissions and subject them to greater central government control. The structure of an independent commission has been undermined by lowering the status of commissioners. The government has not only done this to the RTI Commission but has attacked the independence of almost all statutory authorities, such as the NHRC, Women’s Commission, etc. Their strategy is to bring all bodies under a centralised system and whittle away the structures of accountability that allow people to challenge impunity.

You say organisational structures that ensure democratic functioning are necessary, and that a consensus in society is essential for this. But does there seem to be a consensus today?

The most important consensus in India is the Indian Constitution. It is the idea of India that lays out our foundational principles and institutional structures required to help make them a reality. A combination of policies that promote inequality and facilitate cultural hegemony has challenged and dismantled constitutional principles. Legislations like CAA and so-called love jihad laws in some states are designed to promote cultural divisions. Laws like UAPA and their completely indiscriminate application have undermined democratic space. The Directive Principles of State Policy have been ignored since market fundamentalism took over the economic policy paradigm.

You work with the underprivileged and promote fundamental rights. Today, the poor have been completely marginalised. How can India change this?

The Constitution-writers sought to unite a society divided by caste, religious and ethnic differences by evolving shared ethics of justice and equality. So, we should continue working hard to bring the constitutional principles into practice by questioning deviations from them, whether through legislation, policy, or restrictive government action. India needs inclusive leadership that brings people and communities together. It needs economic policies that empower the economically marginalised with their right to a share in resources, and a consultative, deliberative and participatory democratic framework.

Do you fear the Constitution will be changed? If so, why? Could you elaborate?

People close to the ruling dispensation are mobilising with a resolve to replace the Constitution with a “Hindu Rashtra”. So-called Dharam sansads are issuing open calls that combine majoritarian religious identities with electoral politics for a new constitution and taking up arms, if necessary, to make that happen. The state machinery looks the other way as this blatant anti-constitutional mobilisation takes place.

It is an irony that the underprivileged have been pushed to the margins. The decision-maker is no longer the political system. The visible government panders to economic interests while powerful corporates determine fiscal policy. Social and democratic structures are being reshaped through the policy compulsions and imagination of a politics based on the “religious identity” that powers this government. A perpetual right to dissent is necessary to take on vested interests in the socio-economic structure—as Dr BR Ambedkar so clearly enunciated in his warning to the Indian nation while he handed over the draft of the Constitution. This is being undermined by shrinking democratic space and weakening independent institutions.

In an electoral system dominated by money and elite power, the marginalised are left to fight for economic and social equality only through their vote. This right is only one of many necessary conditions for a functional democracy.

How is this so? Could you elaborate?

There is a great reaction to equality from the two stated positions. The first is the secular nature of the Constitution. This is threatened by bringing in the dominant religious structure to introduce a hierarchy among citizens. This is exemplified by the Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019, the anti-conversion laws and the use of UAPA. Economic equality guaranteed by the Constitution is threatened by neo-liberal economics and the trickle-down theory by the increased hiatus of income, wealth and access to resources. The Oxfam inequality report shows how during the pandemic (March 2020 to the end of November 2021), the wealth of 142 Indian billionaires increased from Rs. 23.14 lakh crore to Rs. 53.16 lakh crore. Meanwhile, more than 4.6 crore Indians are estimated to have fallen into extreme poverty in 2020.

You have worked with craftspersons, artisans, and people working in the informal sector, many of them facing a loss of work. Can you tell me more about their conditions and how they are coping?

Crafts are affected by the neo-liberal policy and shrinking state support. The pandemic further eroded the already handicapped rural craft professions. The latter shrank their income and markets further. Ninety-four per cent of the Indian workforce is in the informal sector. They power the economy and production but live in extremely precarious conditions. For many, even survival is threatened, and, therefore, it is difficult to say they are able to cope.

The pandemic gave us an idea of how vulnerable our workforce is. One small percentage of corporates increased their wealth by large amounts while enormous numbers of people were pushed into poverty and destitution. It is an unacceptable scenario, not good for the health of any society or country. Yet, we cannot just blame the government. Our privileged classes are driven by greed and the desire to accumulate more and more without any concern about the massive numbers of vulnerable people. We are all connected, and this uncaring attitude will come back to haunt us all in fundamental ways.

The new labour laws have made unionisation and protest even more difficult. What lies on the road ahead?

The new labour laws are also part of the framework that panders to corporate profits at the cost of labour rights secured over many decades of workers’ struggles in independent India. This includes undermining the right to organise, articulate, and freedom of expression. The Industrial Relations Code, 2020, by curbing the right to strike and demanding notice of 14 to 60 days before a strike and raising the bar for recognition of unions, is directly destroying the right to freedom of association guaranteed in the Constitution.

Similarly, in the name of streamlining labour laws, many rights such as wages and social security have been undermined. The labour codes should be repealed, and any labour reform must be participatory, through a consensus with the major labour unions and numerous unorganised-sector labour groups. The future of raising workers’ voices against the denial of economic rights lies with the unorganised sector. Entire communities and groups of citizens are affected by labour laws, climate change, and profit-driven economic policies. But the practice of raising their voices has depended not so much on unionisation as the coming together of similarly affected groups for some time to seek redress. This new form of organising will sustain the voices of people demanding economic rights in the current mainstream framework.

The Modi government has been steadily de-funded MGNREGA. Do you see a time when the central government will wind it up?

There is an effort to stifle and destroy the economic structure of the MGNREGA, which has evidently and palpably sustained rural people even during the pandemic and mass migration. The Modi government was forced to turn to MGNREGA and the Food Security Act, 2013, to deliver entitlements and save millions of families from starvation and destitution. Nevertheless, its constant effort has been to undermine and question the rights-based nature of these and other laws. Everything is sought to be placed in a favour or dole framework. The Prime Minister said, “Modi ka namak khaya hai”, to ask for votes based on food grain distributed through the Public Distribution System, thus placing a “right” within a feudal framework of distributing largesse. The Modi government would probably like to have MGNREGA as a scheme whose funding it can increase or decrease as per its own priorities.

However, MGNREGA is a law and not a scheme. Therefore, the right to ask for guaranteed employment is established as a legal right. Since the law gives workers the right to demand work, no government can refuse employment without going against the letter and principle of this law. The government has been trying to squeeze it by drying up its funding and undermining its demand-driven framework. However, budgets for MGNREGA can only be seen as tentative outlays. If demand for work rises, the government is legally bound to make work and wages available.

(Rashme Sehgal is an independent journalist.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.