Here are Asaduddin Owaisi’s Hindu Candidates in Uttar Pradesh

There cannot be a better riposte than Lalita to the Bharatiya Janata Party’s campaign on love jihad, a term the party invokes to accuse Muslims of faking love and marrying Hindu women to convert them to Islam. Lalita was drawn to Iftikar Ahmad despite their 19-year age difference. They married in 2016.

“He follows his religion, I mine,” Lalita said to me. Conversion to Islam would have deprived Lalita, a Jatav by caste, of her Scheduled Caste status. This has enabled the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM) to field Lalita from the reserved constituency of Nagina, in the Bijnor district, where the party polled 4385 votes in 2017.

Lalita is one of the nine Hindu candidates whom the AIMIM had fielded until 31 January. Projected by the BJP as incontrovertible evidence of Muslim intransigence and belligerence, AIMIM leader Asaduddin Owaisi’s very presence is said to enrage Hindus into forgetting their caste and class identities—and voting as Hindu.

This backdrop makes it curious why the nine Hindus opted to contest on the AIMIM ticket. Was their choice-driven solely by the compulsion of securing a degree of Muslim support for themselves? Or did their choice also have an ideological element to it? I spoke to eight of the nine AIMIM’s Hindu candidates to figure out their intent.

Mixed Marriage, Double Engine

On the day I called Lalita, her husband Ahmad answered the mobile. Lalita, he said, was campaigning in another part of Nagina. Ahmad was the Congress district president from 2018 until he joined the AIMIM six months ago. “Wherever I would go, I would be asked about the riots that took place under the Congress regime. Or why the Congress had the locked gates of the Babri Masjid opened. I would be ashamed,” Ahmad said.

The failure of the Congress to revive itself in Uttar Pradesh could have been the other, albeit unsaid, reason to jump ship. Or perhaps he could not pull off a Congress ticket for Lalita.

Lalita and her husband Iftikar

The couple’s decision to join the AIMIM has had some Muslims taunt them. They are often asked why Owaisi has come all the way from Hyderabad to fish in Uttar Pradesh politics. Their innuendo is unmistakable: Owaisi is playing the BJP’s game to prevent Muslims from consolidating behind the party likely to vanquish the BJP.

Their counter is their own questions to them: Why does Samajwadi Party leader Akhilesh Yadav field candidates in Maharashtra or Madhya Pradesh? Why does Bahujan Samaj Party’s Mayawati fight elections in every state? Ahmad said, with his voice betraying bitterness, “Come elections and Muslims want to vote for the SP or the BSP. But when mob lynching occurs, or issues such as the Citizenship Amendment Act surface, they want Owaisi.”

This has only deepened Ahmad’s conviction that the Muslim community needs to build its own leadership. “That leadership has to be Owaisi’s,” he said. Later, when I spoke to Lalita, she said, “Both Muslims and Dalits will vote for us, because Ahmad and I represent two marginalised communities.”

Indeed, Hindu-Muslim marriages can, theoretically, be as electorally advantageous as the promise of “double-engine” governments.

Queen of Ambitions

On the AIMIM’s list is also Gita Rani, contesting from the Dhanaura reserved constituency in the Amroha district. Like Lalita, Rani is a Jatav and married a Muslim—Haroon Saifi—in 1999.

But Rani and Saifi are, in some ways, opposite of Lalita and Ahmad. For one, Rani is 48 years old, elder to Saifi by three years. For the other, she is politically experienced. In 2012, she contested from Dhanaura on the Rashtriya Mahan Dal ticket—and, significantly, polled 11,643 votes.

After that, she drifted to the Congress but left the party a month ago. “I worked hard for the Congress for eight years, but I was denied the ticket. AIMIM offered me the ticket, so I went. Congress workers, anyway, do no work,” Rani said.

Rani hopes to cash in on the popularity of Owaisi among Muslims to gather their votes, particularly of the Muslim caste of Saifi, to which her husband belongs. She hopes her Jatav identity will net her the votes of her caste. About the AIMIM being the BJP’s B-team, Rani said, “Look how Behenji [Mayawati] benefited the Jatavs. Muslims, too, need a raja.” And that raja, for her, is Owaisi.

It is hard to tell whether the elections made her perceive the importance of Owaisi. Or whether Rani and Saifi were always Owaisi fans, much like Congress leader RPN Singh, who turned out to be, weeks before the elections, a secret Hindu nationalist.

Not all AIMIM’s candidates in reserved constituencies are married to Muslims. Sunil Kumar, for instance, is not. A BSP worker, the AIMIM’s offer to field him from Kannauj held out the promise that he could improve his political status overnight. He migrated to the AIMIM. Kumar thinks the alliance between the Jan Adhikar Party of Babu Singh Kushwaha, once an important member of the BSP, and the AIMIM will have the lower castes and Muslims voting for him.

Kannauj bolsters the theory that the BJP could gain because of the continuous fission process afoot among subaltern groups. This is why Opposition leaders accuse Owaisi of deliberately fragmenting anti-Hindutva votes to assist the BJP clandestinely. “Really?” Kumar mocked. “If AIMIM is the BJP’s B-team, then what will you call the SP? Did not Mulayam Singh Yadav’s daughter-in-law join the BJP?”

Pandit from Bihar

It is easy to fathom why the AIMIM is not anathema to Dalits. They, like Muslims, have experienced the sharp edge of Hindutva, which seeks to keep intact the traditional Hindu hierarchy. From this perspective, it is surprising politicians belonging to the upper castes, the most steadfast supporters of the BJP, should have chosen to jump on the AIMIM boat.

Pandit Manmohan Jha is one among them. In 2010, he joined the Samajwadi Party and was, until he quit the party on 15 January, its president of the Sahibabad Assembly constituency in Ghaziabad. On 17 January, Jha became the AIMIM candidate for Sahibabad. When Jha spoke to Owaisi on the phone, he greeted the leader with As-Salaam-Alaikum. Jha gushed, “But Owaisi said, Panditji namaskar. And namaskar to your father and mother also.” Jha teared up because he was reminded of his dead parents.

Pandit Manmohan Jha

A Brahmin from Sitamarhi in Bihar, Jha is taunted for joining the party opposed to the Hindus. But he mollifies them with some examples. For instance, Mayawati would once chant: “Tilak, tarazu aur talwar, inko maro joote chaar (Beat the upper castes with shoes).” Today, she is wooing the Brahmins. The Samajwadi Party speaks of the Other Backward Class, but its leader, Akhilesh, has promised to install the tallest statue of Lord Parshuram, the mythological hero of the Brahmins.

Jha tosses to his critics the example of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In 2014, Modi said the nation was in danger—and came to power. In 2019, he said Hindus were in danger—and he came to power. And now, he says he is in danger.

“Owaisi has it in him to realise Dr Ambedkar’s dream of equality.” Jha said. Perhaps, because of his own identity as Brahmin, Jha added, “Owaisi talks about every individual who is poor, irrespective of their caste identity.” With his constituency home to three lakh Bihari voters, Jha thinks that he, on paper, has numbers to construct his castle of hope.

Mr Strange

Ravi Shankar Jaiswal is arguably the most peculiar of AIMIM’s nine Hindu candidates. He has a flourishing wood and furniture business in district Bhadohi. His idea of charity includes giving three quintals of wood free to anyone who cannot afford to cremate their loved ones. He also does not use WhatsApp.

Believing his charity work would persuade people to vote for him, Jaiswal stood as an independent candidate in the 2012 Assembly election. He polled just 540 votes in Bhadohi. Stung, he withdrew from the electoral arena, confining his political activism to advocate that people should vote for a candidate according to their merit rather than the party they support.

Jaiswal said he stumbled upon the video recording of Owaisi’s speeches and was inspired enough to travel all the way to Lucknow to listen to him, in flesh and blood, on 26 February. He said he had not been taunted even once for accepting the AIMIM ticket. Perhaps his charity work prompts people to remain silent, for every Hindu needs wood to cremate the dead. “Like the elephant, I walk the path I choose without even caring to listen to who is speaking what about me,” Jaiswal said.

Buddha’s Bhakt

Owaisi’s videos on YouTube was also an attraction for Vikas Srivastava, particularly the AIMIM leader’s speech on the 2013 Muzaffarnagar riots. A Kayastha, he joined the BSP in 2012. Explaining his choice, Srivastava said, “I am very inclined to Buddhism. I appreciate Gautam Buddha’s teaching against caste.” He sighed and added, “Only if Mayawati had not deviated from [BSP founder] Kanshi Ram’s path….”

Vikas Srivastava

When Srivastava asked for the BSP ticket to fight the Zila panchayat election last year, he realised the rot in the BSP ran deep. “Do you know I was asked to pay Rs. 5 lakh for the ticket,” he asked, pointing out that he was then the BSP president of the Ram Nagar Assembly constituency. No less a significant factor behind his decision to join the AIMIM was the bias of the Uttar Pradesh Police he witnessed during the 2020 lockdown. “They would beat anyone who violated the lockdown. But a Salman would get more dandas than a Mukesh,” he said.

On 6 July, he enrolled in the AIMIM. Two days later, he organised a welcome ceremony for Owaisi in Ram Nagar. “I gave him a framed picture of Babasaheb Ambedkar,” said Srivastava. Joining the BSP was bad enough. His crossing over to the AIMIM raised the hackles of the upper castes. Srivastava’s response was to tell them that Owaisi contributed Rs. 6 lakh to the Prime Minister’s National Relief Fund in 2013, when flash floods inundated Badrinath and Kedarnath, in addition to the AIMIM supplying relief kits and medicines worth Rs. 74 lakh.

For a man harbouring mere Panchayati ambitions until last year, Srivastava now hopes, courtesy the AIMIM, of entering the Vidhan Sabha. His political status has been enhanced. But he is likely to find the going tough, for the AIMIM, in 2017, had bagged just 1,196 votes in Ram Nagar.

The English Speaker

For all their professed fidelity to Owaisi, all six candidates profiled above joined the AIMIM very recently, mostly because they were denied tickets by the parties of which they were members. However, among the AIMIM’s Hindu candidates, there are two whose trumpeting of Owaisi has a genuine ring to it.

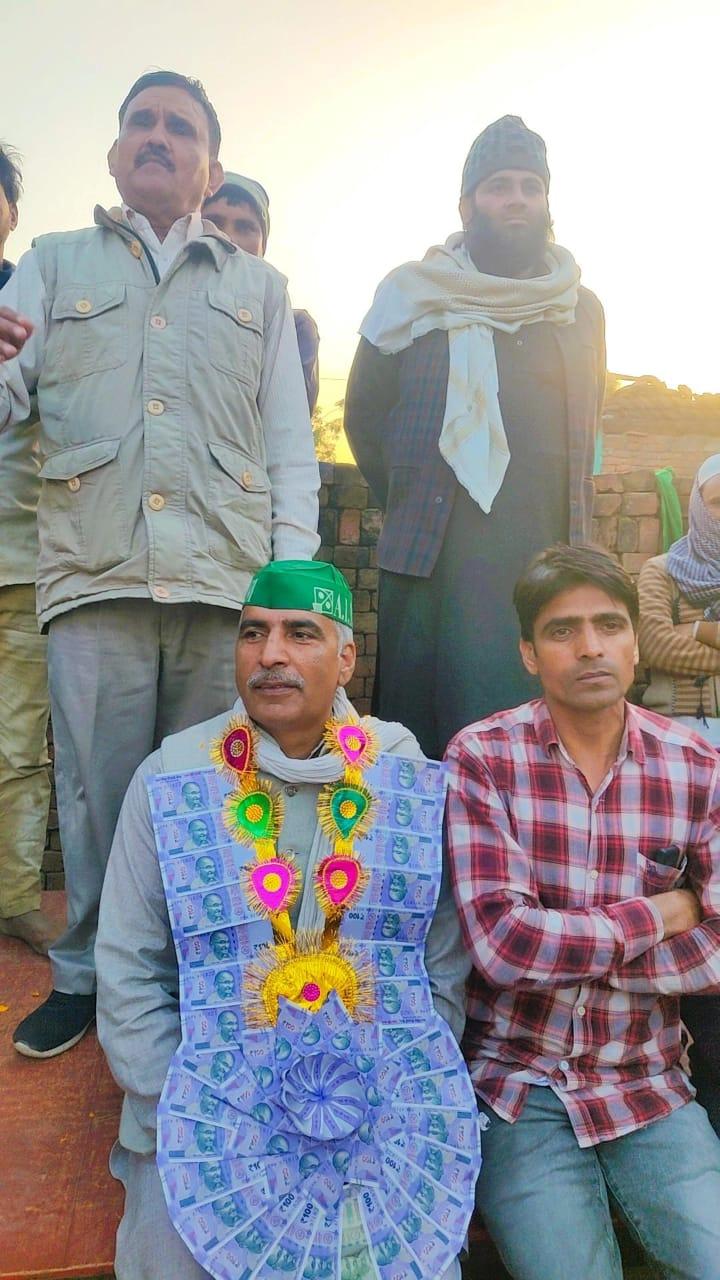

Take Bheem Singh Balyan, a Jat contesting from Budhana in the Muzaffarnagar district, which was witness to the grisly rioting in 2013. Balyan is media savvy. On hearing I am a journalist based in Delhi, he took to speaking in his idiomatic English. He said the bloodshed repulsed him.

Bheem Singh Balyan

“Jats are not religious. Their emotions were deliberately stoked to turn them against Muslims. But they have now seen through the BJP’s game,” Balyan said. In the months after the rioting, Balyan helped AIMIM boys, most of them daily workers, to provide succour to the community.

Balyan said Owaisi’s visit to Muzaffarnagar left him impressed. “Do you know he financed the marriage of many Muslim girls?” And then, out of the blue, he remarked, “It is only through him Ambedkar’s dreams can be fulfilled.” He paused and added, as all candidates do, “I am in the fight.”

The Long-Distance Runner

None of the AIMIM’s Hindu candidates can match Vinod Kumar Jatav, who has truly proved to be the long-distance runner for the party, which has nominated him to fight from the Hastinapur reserved constituency in the Meerut district.

Vinod Kumar Jatav

In his late 30s, he took to politics very young, hovering around Prabhu Dayal Balmiki, who became a Samajwadi Party MLA in 2002. Balmiki had the government appoint Jatav as his personal assistant. In 2007, after losing the election, Dayal called Jatav and wondered aloud, “What will you do now as I am no longer an MLA?” It meant Dayal would no longer pay Jatav.

He found employment in Mawana Sugar Mills, got married in 2012, and then opened a shop in Meerut’s vegetable mandi, working as arhatiya or middleman. In 2012, he fought on the ticket of the National Loktantrik Party—and bagged just 571 votes.

“I had Muslim friends in Mawana,” he said. It is because of them he happened to chance upon Owaisi’s videos. Jatav said he was struck by Owaisi’s two qualities. For one, he always spoke of marginalised communities, especially Dalits and Muslims, and Dr Ambedkar.

For the other, Jatav loved Owaisi’s belligerent style of delivering speeches, his chutzpah. He said, “I thought Ambedkar must have been like Owaisi, for Babasaheb, too, took on the entire political class alone.” Hyperbole?

Well, Jatav has been a lone-ranger himself. He joined the AIMIM in 2013. It is Meerut’s tradition that political parties pitch tents at the city’s Eidgah during Eid and Bakrid festivals. Jatav began to do the same for AIMIM. “All tents were manned by Muslims. They would go to pray, while I watched them from afar.” His shop sported a large banner of the AIMIM, with Owaisi’s photo.

He recalled some of the barbs Muslims would fling at him: “Owaisi has come to Uttar Pradesh to get Muslims killed. You have wasted your life. We Muslims will never vote for the AIMIM.” Yet Jatav did not leave the AIMIM and, in fact, began to bat for Muslims in public meetings district officials would periodically hold.

At one such meeting, held around the time Chief Minister Adityanath began to crack down on slaughterhouses, Jatav presented a memorandum to the Senior Superintendent of Police. It asked, “Why is the administration troubling Muslims in the name of the cow?” The memorandum had Jatav’s name. The SSP, flaring up, demanded to know what Jatav had to do with the slaughterhouse issue.

The Opposition’s reluctance to publicly stand up for Muslims against attacks from Hindutva have turned the Muslim youth into “big fans of Owaisi,” Jatav said. He refused to take the bait I tossed at him: Admiration for a leader does not necessarily mean votes for his party.

This is more than proved by the AIMIM’s performance in 2017. It contested in 38 seats and polled just 0.24% of total votes polled in Uttar Pradesh. However, in the 38 seats the party contested, its vote-shared was 2.4%. In Sambhal, the AIMIM polled 59,303 votes.

The Future

As Uttar Pradesh is said to have become a close contest between the Samajwadi Party-led alliance and the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance, a ballooning AIMIM kitty could prove disastrous for the former. Such a scenario is what Owaisi has been advocating—until Muslims stop voting for the non-BJP parties, they will not work for the community’s uplift. The forthcoming election will demonstrate the popularity and credibility of Owaisi’s thesis among the Muslims of Uttar Pradesh.

No doubt, many AIMIM candidates are weathervanes and are unlikely to stay on the AIMIM boast as it sails into the future. In the AIMIM, those who hold organisational posts matter infinitely more than candidates. As long as the AIMIM can show it can field little-known candidates and become a cause of parties losing or winning in elections, non-BJP parties, for their political survival, could become amenable to cut a deal with Owaisi. Indeed, the only way out for non-BJP parties to insulate their Muslim supporters from Owaisi’s charm offensive is to stand up for Muslims, whose votes often helped them come to power in the past.

The author is an independent journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.