Dichotomy of Gold: India and the Moscow Olympics

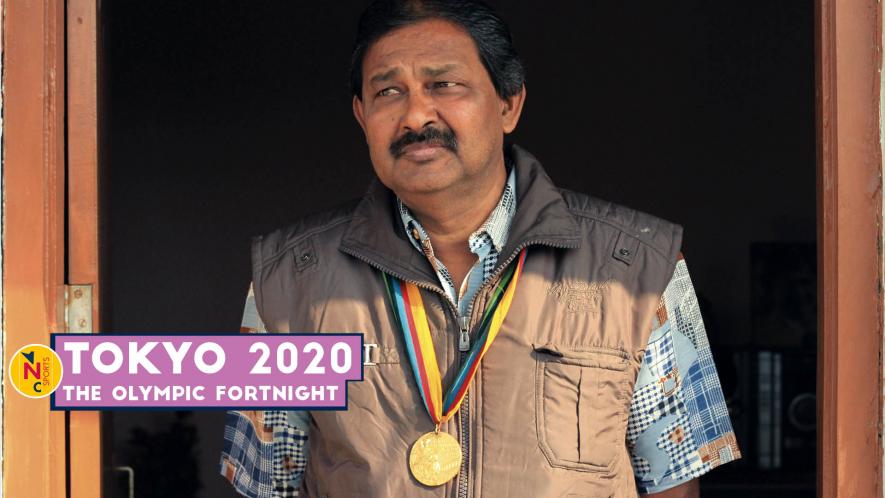

Ravinder Pal Singh played centre half for the last Indian hockey team to win a medal at the Olympics — gold in Moscow 1980 (Pictures: Roanna Rahman).

PART I

On a winter afternoon in 2016, I touched an Olympic medal for the first time in my life. It was cold, and smelt of naphthalene balls. After over three decades of storage, the plating was bubbling up in places. The colour had completely chipped away on one side.

Holding it was, on the whole, somewhat unsatisfactory. If you ever touched a medal that did not belong to you, you’ll identify with this feeling that washes over you. A feeling of unworthiness. You feel like a voyeur and a thief.

The medal was gold. On the obverse, it details the year and edition of the Olympiad it was minted for. The XXII Olympiad, Moscow, 1980. The reverse, designed by the sculptor Ilya Postol is modernist. Stark, simple. All clean lines and curves. An Olympic flame burns high. Four lanes curve around it. On the right corner is the official emblem of the Games — Vladimir Arsentyev’s amazingly minimal depiction of a Moscow skyline. Five tracks and a five pointed star. For context, Tron was still two years away. The grid was invented in Moscow.

At first glance, you may believe the front and the back to be completely different objects. From different times.

The day I saw it was a great afternoon in Lucknow. The sun had come out after many days of dense fog. We were on a terrace bathed in the December light. My companion, a photographer, was capitalising on these superb circumstances to shoot a picture of the medal from every possible angle with every manner of shadow that would allow it to look majestic. The sunlight bouncing off the gold made this exercise incredibly difficult.

Click | For more stories/videos from ‘Tokyo 2020, The Olympic Fortnight’ series

Ravinder Pal Singh stood on a corner of the terrace, with his Tibetian terrier, Pasha, in his arms, watching this scene play out in front of him. He’d won the medal at the age of 20.

His friend Pappu, who had helped secure this interview (Bhai saab unknown number nahi uthatey) was standing at the diagonally opposite corner, on the phone, looking into the distance, while chattering away.

“Bhai sa’ab, aaj shaam chai (brother, how about tea in the evening)?”

Ravinder Pal looked away from us to nod in affirmation. He turned back and said, “Shaam mein karein baat (Can we talk in the evening)?”

It had been 20 minutes since we entered his front door. We’d seen his medal. We knew when he won it. We’d got pictures of him, it, but nothing in between. But we were being dismissed without a story. Because it’s how he preferred it.

The assumption that storytelling is an intrinsic part of human nature is an outright lie. The cave paintings, the bards with the scrolls, Homer’s idiocies, the Ramayan’s fallacies, all of them were storytelling with a neat objective towards gain. If you remove personal gain, storytelling becomes a meaningless exercise, something they now call documentation. If you have ever entertained yourself looking at documentation [Wikipedia anyone?] you know that storytelling wasn’t the aim, fact collection was. Story telling requires participation. At the very least, a participant with a story and a willingness to tell it. Ravinder Pal is the former but not the latter.

He is one of many men from Lucknow [so many that all of Lucknow’s major stadiums are named after hockey players] to have won an Olympic gold medal in the game. If you had to list all of them out, he is the name you’d forget. He goes to a chai shop near the KD Singh Babu Stadium (the original hockey stadium), and moves about unrecognised by all who do not know him closely. He goes there because he can pass by unrecognised by all who do not know him.

“Bhai sa’ab aap abhi baat kar leejeye (brother you please talk to them),” Pappu said from the other end of the terrace, “Shaam ko hum karenge (evening we will chat).”

PART II

When he did eventually sit down, Ravinder Pal was an articulate, if somewhat a reluctant subject. The reluctance manifested in his ability to speed up stories he didn’t care to tell, and plant himself on ones he did. Perhaps he understood that telling a storyteller an incomplete story was a subversion in itself. He detailed his childhood in hockey with a simple swift timeline, where, having lost his mother very young, and being brought up by a policeman father, it was natural he would take to sport rather than study. “Woh bhi football hockey khele hue thhe. Agar hume woh zyaada padhte hue dekhte thhe toh bhaga dete thhe. ‘Yeh kya natak kar rahe ho’, bolke bhaga dete thhe (He had played football and hockey himself. So, if he caught me reading too much he would chide me, asking ‘what is this drama’).”

He joined the sports hostel in Lucknow the year after its inauguration. He went there at the same time as a young forward by the name of Mohammed Shahid. The rest of the interview is a Shahid tribute piece with fewer words than adoring (and sympathetic) sounds. This went on for an hour. My notes from this hour simply read: Shahid. Kya player thha. Goal in ‘80 final (?).

Also Read | Brazil Sets Up Olympic Camp in Portugal as Pandemic Rages At Home

We get back to the gold eventually. This is Indian hockey’s last gold medal at the Olympics. It has been four decades since India got that far in the hockey competition at the Games.

In Netflix’s Dark, the protagonist Adam drones on at the beginning of a particularly volatile episode, “Life is just a collection of odd circumstances''. Ravinder Pal Singh uses the loosely translated Hindi word paristithi often in conversation. His deviation to sport in his childhood (kuch paristithi aisi thi, humari ma guzarne ke baad - circumstances were such after the death of my mother…’). His enrollment in the hostel “Pitaji Police mein thhe aur bhaiya bhi kaam karne lage. Ghar ki paristithi…’ - my father was in the police and my brother was also working. So the circumstances at home...).

How a team of misfits won a gold in Moscow?

“Dekhiye, yeh chupaane ki koi baat nahi hai, paristithi aisi thi ki hum akele strong team thhe. Hume pata tha final toh khelna hi hai (there is nothing to hide here. The circumstances were such that we were the only strong team around and so reaching the final was a given),” he finally said, settling into his sofa, Pasha preening right next to him. “None of the good teams of the time were going to be there. Spain was the only good European side taking part. I think they were European champions so maybe there was some credibility there [Spain, in fact, finished fourth in the Euro Hockey Championship in 1978. The top three boycotted Moscow], but the rest of the teams, aisa bolna nahi chahiye (I should not say this), but they didn’t deserve to be there.”

Armed with that information, reanalyse India’s 43 goals in six games across the tournament. Also reanalyse that they drew two games in the preliminary round (against Spain and Poland). They beat Tanzania 18-0. Cuba 13-0. Two years later, in Delhi, they lost to Pakistan 1-7 at the Asian Games. You understand where this is going.

This is Indian hockey’s last gold medal we are talking about. There are reasons for that. It was a weird decade. In 1975, the Indians won the World Cup. The next year at the Olympics in Montreal (the first time the competition was played on turf) they became the first Indian side to come back home without a medal in the sport’s Olympic history. In 1978, Pakistan won the World Cup. India did not feature in the top four. And then, 1980 happened.

An Olympics where nine of the 12 teams initially drawn up for the competition pulled out. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan led to a worldwide boycott of the Games. The ideal sporting event, where the simple idea — what matters is what happens on the pitch — acquired a moral worth that can be debated for time. At the Olympics, strength means muscles, discipline means dedication and patriotism means teamwork. This is a myth. The Olympics did not, will not, and has not transcended power struggles. The Greek gods on Olympus meddled regularly in love and war. It makes perfect sense that the Olympics they inspired were stirred by them too.

Also Read | Bajrang Punia Enigma: A Patient Indian, An Impatient Wrestler

All barring two members of the Indian 1980 Olympic squad were debutants at the Games. After the debacle of the 1978 World Cup — marred by infighting, the team splitting into camps, a general lack of discipline and an overeagerness for shopping — the federation opted for a fresh start (a brilliant turn of phrase that only signifies a reassertion of power). The two seniors, Vasudevan Baskaran, and Bir Bahadur Chettri marshalled the fresh start into some sort of shape to win the gold from a depleted Olympics.

And two years later, came another fresh start. Of the 16 who played in Moscow, only six made the squad for Delhi in 1982. Of those six, Zafar Iqbal and Mohammed Shahid were anomalies, men who would have made the squad for any country on the planet. Ravinder Pal did not make the cut.

“You probably know this, but it is worth saying again,” Ravinder Pal said. “Politics in sport really ruins sport.” He details how lobbying and jostling for control on the team became a feature of selection. Players from Punjab were easily integrated into the squad. Players from the south, easily ignored (“Baskaran sa’ab ko drop kar diya thha. Socho (even Baskaran sir was dropped from the team)”) and players from UP, if workmanlike rather than gifted connoisseurs, mostly caught in the middle.

PART III

Ravinder Pal retired from international hockey after the 1984 Olympics. A chronic spinal injury made playing on turf harder every time. On the domestic front, though, he stuck around for a few more years, playing for Bagan in the Kolkata league (“bohot khatarnak competition hota tha”) and State Bank of India (by whom he was employed his whole career). His gold sat in storage. He dabbled in coaching with departmental teams in the police and the Army, before washing his hands off it all.

“Politics hume pasand nahi hai (I never could stand politics). And almost anything to do with hockey at the time was politics. You needed to pull favours, or cajole someone. And in any case, I didn’t want to go through a grind and get a coaching degree,” he said. “NIS woh karte hain jinko naukri nahi milti (NIS diploma is pursued by those who don’t manage to land a job). I had a job with SBI. Why would I throw that away for an uncertain future in coaching?” And so gradually, over time, he disappeared. Prior to the 2016 Olympics he made an appearance at a function organised by Hockey India, commemorating gold medallists over the years. But mostly he has remained invisible.

This isn’t an anomaly though. There are very few members of those ’80s teams who burnt themselves in memory (sometimes even after covering themselves in glory). It was an odd generation, one that endured Olympic success rather than flaunted it.

Also Read | To Be or Not to Be: Olympics No Hamlet for Cricket

Later that evening, we landed at the chai shop. Ravinder Pal was in his element, jovially ribbing one of his friends who worked at SBI, entertaining everyone with jokes and passing around copious amounts of tea. Later, he took us out for dinner. A bachelor, he had nowhere to be and yet in the gesture it was made clear that he was being nice because he wanted to get rid of us nicely.

“Nah. I don’t really watch much hockey anymore,” he said as I wolfed down kababs. “I love watching the Premier League. I have a simple routine. I wake up a bit late, rustle up some breakfast, do some reading, then head off to Pappu’s shop. I’m there till evening. You have come to our chai session. I will go home and watch some football. Then do some more reading. Everyone knows where to find me basically. I don’t pick up phone calls and text toh karna hi nahi seekhe hai (never learnt how to text).”

We bid our goodbyes and head off in opposite directions. In the four years after I sporadically send him texts on public holidays. He responds once every year. There is no consistency when he may do so. He has never picked up my phone calls since. Pappu does. We talk. He tells me about him and promises to put him on the line. “Par aapko pata hai na. Bhai sa’ab phone pe toh baat hi nahi karte (but you know it well right. He does not talk over phone).”

They minted 444 gold medals for the Moscow Olympics. 204 of those were awarded at the Games. 16 reside in India. Ravinder Pal Singh’s does not even reside in his house. They are locked away at his sister’s, taken out on the rare occasion he has a story to tell.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.