Runaway Military Ambition of a Shrinking Economy

Representational Image. Image Courtesy: NDTV

If the Indian government cared about security of citizens, it would have begun by ensuring that they do not live under a system of governance where no rules apply, where law enforcers do not display complete ignorance of the law and Constitution, and where lawlessness and uncouth language is paraded as the new ‘sanskari bhasha’.

It makes one wonder—how one can feel confident about the ‘nationalist’ credentials of a government that sows seeds of bitter particularities. A government which has shown through its conduct that it cares too hoots for an inclusive idea of India, and instead promotes and pursues a divisive policy at home. So let us turn to the military budget with this cautionary note in mind.

Burgeoning Expenditure

Contrary to accepted wisdom India’s military expenditure is much too high and reflective of the colonial habit of militarily suppressing Indian people. This habit has persisted over decades. And a significant amount of the budget is on account of using the ‘armed forces of the Union’ for prolonged wars at home for decades on end.

Out of a total expenditure of Rs 30,42,230 crore of the government of India for the financial year 2020-21, the allocation for defence, including defence pensions, stands at Rs 4,71,378 crore or $67 billion. This is more than 2.1% of the GDP. Defence pension is at Rs 1,33,825 crore and rose by nearly 14% in contrast to overall defence allocation rising 3%.

Going by SIPRI’s definition, in order to derive the real size of India’s military budget, the allocation of Rs 85,184 crore under “Police” for the Ministry of Home Affairs too must be added. This comprises the central para-military formations such as the Assam Rifles, Indo-Tibetan Border Police, Border Security Force, Sashastra Seema Bal, Central Reserve Police Force, National Security Guard etc. All these forces fall under what the Constitution calls the “Armed Forces of the Union”. They are modelled on colonial Irish constabulary of the 19th century and are also trained along the lines of the army’s infantry. The allocation then rises to Rs 5,56,562 crore, that is, . nearly 2.5% of the GDP, or $79 billion

By no stretch of imagination, for a woefully resource-poor country faced with an economic slowdown, is this allocation ‘inadequate’. According to SIPRI 2019, whereas China spends 1.9% of its GDP on military ($250bn), the US spent 3.2% of its gargantuan GDP on military ($649 billion). So, although Indian military expenditure is modest in contrast to US and China, given the size of our economy it is still a large allocation.

The expense outgo on military is justified by pitching India as a rising power that needs to expand its security footprint, and in view of a two-and-half-front war scenario confronting India. While military experts write about the threat posed by China and Pakistan, what is conspicuously absent is analysis and assessment by the government regarding the nature of the threat posed, and therefore, what is required to meet this challenge. Former National Security Advisor, MK Narayan wrote recently that what is needed is “a well-formulated defence White Paper, putting different threats and dangers the nation faces in perspective, alongside steps taken to meet these challenges”.

Had the Congress-led UPA government issued a White Paper, this suggestion would have acquired greater weight. Nevertheless, he is right to question the “coloured” narrative about China as an aggressive power bent on imposing a Sino-centric world order. He has argued for an “in-depth study” to find out if China poses a “direct threat to India’s existence”. In other words, is China a rival neighbour or an adversary and an enemy?

There is a vast difference between rivalry and animosity.

For instance, does the Indian Navy require two or three or more aircraft carriers to meet the rising presence of China in the Indian Ocean, when China, as one of the two superpowers, and the world’s second-largest economy, needs to protect its global interests and therefore needs a larger military footprint? Just as India does not frown upon former colonial powers increasing their naval presence in the Indian Ocean region, on what basis should India consider Chinese naval presence as a threat to it? Has there been a single incident like the US 7th Fleet threatening India in 1971?

Besides, India is also trying to acquire bases in the Indian Ocean region to protect its own interests. Then why whip up fears over China’s rise, which challenges the hegemony and domination of the United States and its NATO allies, a veritable list of evildoers of the past and aggressors at present [ask Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Libya and now Iran].

By exaggerating the threat posed by China, the old colonial powers want to get their former colonies to get on board their renewed bid to reimpose their imperial control over the world. The recently-held Munich Security Conference, which follows the last NATO conference, also spoke about reviving and expanding NATO and the European Union’s military power globally. The right-wing assertion is not always insular—it is also hegemonic. Then what does the Indian establishment have to say about the expanding footprint of NATO/EU? Does India feel that US-led NATO’s aggressive posture vis-a-vis China and Russia offers India an opportunity? Or have they considered that once they gang up against China and Russia, India will be next—either to fall in line or face the same music? Because imperialism waits to strike at the right moment.

Hence there is much to be said in favour of a White Paper.

However, in order that we are not caught off-guard, our country has to maintain a “dissuasive military posture” vis-a-vis China. But if money does fall short to procure military weapons and systems to maintain this posture, it would not be because allocations are low, but because of the rising manpower costs, especially the burgeoning weight of defence pensions.

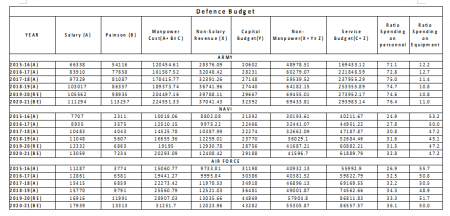

The table below shows that the burden of manpower costs plagues the Army, and not the Air Force or the Navy, which have a fairly reasonable revenue and capital budget allocations.

The scale of the problem can be grasped from the fact that in contrast to the Defence Pension head of budget, for more than 2.06 million pensioners (including widows), civil pension, that is the government’s outgo for its nearly four million employees, stands at Rs 61,169 crore True, DP cannot be compared with civilian pension in so far as the former is entirely borne by the government while in the latter employees contribute to their pension. Besides, the number of years of service and length of service are vastly different, since para-military personnel retire in their late fifties unlike the Services where personnel—not officers—retire after 17 years. However, it is the scale of the pension outgo which invites attention and a comparison.

While there is a near-consensus that the only way in which the spiralling growth of DP can be contained and money made available for military procurement is through manpower reforms, the question is what manpower reforms entail. The low-hanging fruit is to transfer several logistical and maintenance responsibilities to civilians, because civilian manpower costs are low. This may save a few thousand crores, but still not address the issue of the bloated size of the Army.

The proposal to extend the service tenures of four lakh non-combatant service personnel from 39 to 58 years may save Rs 4000 crore, but this falls short of what is needed. All these changes, however good, will not make any impact unless the real reason for the bloated size of the Indian military is addressed.

Cut Where it Matters

The stupendous growth in manpower, both of the Indian army and the para-military forces, for reasons of fighting wars against our own people has rarely been questioned. The Rashtriya Rifles was raised in the 1990s and has 75,000 personnel at present and the colonial origins of the Assam Rifles, with its 64,000 personnel raised to fight our own people, are incongruous for a republic. Arguably, if these two formations are disbanded the military can purge 1,40,000 personnel.

So India suffers not only from “legacy weapons” but also from the legacy of an antiquated “area-domination” approach which requires mass deployment of troops to tackle insurgencies. Indeed this brings other para-military forces into the picture with CRPF, BSF, ITBP, SSB etc, all getting deployed in large numbers in “Disturbed Areas”, armed with AFSPA, and what is more alarming, it brings in regular Army soldiers too. With the Chief of Defence Staff proposing a Theatre Command for Jammu-Kashmir, this use of the Army for internal security purposes will get legitimised.

Yet, few observers bother to interrogate the Army’s expanding footprint in internal security operations, where a sizeable chunk of the forces are deployed. And rare is an instance when a strategic expert raises questions about the policy of prolonged and decades-long military suppression of our own people, which has required this stupendous increase in expansion of para-military forces since the 1970s.

Although the exact strength of Army deployment in Jammu-Kashmir and the North-east are not known, an intelligible approximation of the same is possible.

If the Northern Command of the Army with its two Corps is deployed in J&K, and the III and IV Corps are deployed in the North-east for internal security, then arguably, 3 to 4 lakh soldiers are deployed for internal security. In fact, with the Chief of Defence Staff now announcing that Jammu-Kashmir will have its own Theatre Command it is evident that the colonising project will be pursued by the Indian armed forces in J&K, tying hundreds of thousands of personnel down to what is considered a secondary role for them.

Besides, the salaries, wages, pension and transportation costs of the Army are extraordinarily high because there is constant movement of troops as they are rotated to and from the “Disturbed” areas. And in J&K, post-Pulwama, soldiers are now flown in and out, further jacking up transportation costs.

In other words, unless the Army veers away from its secondary role of fighting our own people, and the focus shifts back to concentrate on their primary role and responsibility to defend the borders, no major reduction can be effected to cut the ‘flab’. This depends on the government’s political will to move away from military suppression of our own people to a democratic political resolution of problems. It was the non-resolution or refusal to address political demands by the government which brought the Army into the fray in the first place. And with the colonisation of J&K having been effected, there is no gainsaying that the Indian Army will carry on with their ignoble mission for few decades more.

Unfortunately, with the Chief of Defence Staff chasing terrorism as the main threat, and the fixation on the borrowed terminology of “hybrid warfare”, the democratic resolution of conflicts at home are far from the government’s imagination or inclination. As a result. tinkering may help cut some flab and save some money, but nothing worthwhile will be achieved which can have a major impact and result in sizeable saving.

How to Raise Money

Does this mean that nothing can be done to save scarce resources from being wasted on wars at home and to find money to fund modernisation of the armed forces?

Well, in India, we need to be prepared for insidious solutions being offered by the government.

The Fifteenth Finance Commission was also tasked with finding ways to address external and internal security requirements of the government. One of its key suggestions is to have a non-lapsable fund. While the idea of such a non-lapsable fund came up in an era when capital allocations remained unspent, we are now in a period where capital allocations just cover the payments for previous purchases, leaving little money for new purchases.

Article 266(1) deals with the Consolidated Fund of India, from which every withdrawal has to be approved by the Parliament. Without a constitutional amendment in this article, a dedicated non-lapsable fund cannot be set up. But a bigger question is where is the money for this non-lapsable fund going to come from? The sale of surplus land with defence-sector units or issuing long-term defence bonds, etc, are being talked about.

While selling surplus land is an attractive idea and issuing special defence bonds provides another way out, but the suggestion of the Ministry of Defence to impose a 2-3% cess on existing income tax to raise money is alarming. The Bharatiya Janata Party government has managed the economy poorly, to put it mildly. Its management of public funds is even worse. It has wiped out surpluses held by public sector Navratnas by forcing them to transfer it to government to meet its revenue expenditure, and it has then forced them to turn to the capital market to raise equity or loan.

Either way, this will pave the way for the privatisation of these PSUs. Recall the government’s taxation policy rewards the fat-cats in India, while forcing wage-earners to shell out more and more by raising indirect taxes. So income tax-payers will be made to pay 2-3% cess to make up for the profligacy of the government, which has squandered public funds on hare-brained schemes. If “national” security was a priority for the BJP then its government would not have reduced the tax burden on the rich and instead used the money to fund military wherewithal. At least, this was an option available to the government.

But the biggest worry is how to ensure that money so raised is invested in the military sector. Unless the money raised by selling land and/or issuing defence bonds or from the cess are strictly kept aside to invest in the public sector units—and not transferred to meet revenue expenditure of the government or transferred to private players—the government would only create a far bigger problem than the one we face now. For instance, raising money through bonds today means creating a debt burden for Indian public tomorrow. Besides, it will amount to expansion of the corporate footprint in the military sector, where they will remain junior partners of foreign Original Equipment Manufacturers or OEMs.

The reason for being sceptical about the government’s plans is on two counts. One, the Modi government is trying to entice the Indian corporate sector to enter the military sector and become junior partners of foreign OEMs. Trouble is that neither Indian nor foreign OEMs will invest if they are not assured of large orders, and repeat orders at that. The experience of Larsen & Toubro (L&T), which got the contract to supply a Howtizer called Vajra 9, which they manufacture in a joint venture with South Korean Hanwha Techwin, shows the pitfalls.

L&T has sounded the alarm and said that if the government does not place another order in the next six months it may have to shut their Gujarat-based unit and shift its personnel somewhere else. The government’s response has been to let the Indian private sector know that they will get only a “small pie” from the government and that they must export to keep their plant working. Is this realistic?

The joke is that the government pads up defence export figures by including exports of aerospace parts and components so that a modest export worth Rs 2000 crore can be expanded five-fold to to Rs 10,700 crore. In fact, the prospect of military export appear far-fetched. Where from will the Indian private sector create a market for their joint venture products, which are made in collaboration with OEM? At best Indian joint ventures can supply some parts to OEMs, which they can, in turn, use in the equipment or hardware they export to third countries. But creating a market of their own appears over-ambitious as of now.

In addition, there is confusion about government policy. For instance, a paucity of resources makes the Chief of Defence Staff claim that India will go in for “staggered” acquisition of 114 fighter jets and has declined to construct a third aircraft carrier for the Navy because it is “very expensive”. However, staggered purchase of fighter jets now makes it evident that India might settle for Rafale fighter jets. It is curious that after running down Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd, French Dassault is back discussing a new work-share agreement with HAL! After making a novice private company the beneficiary of offset investments, which left Dassault in full control of the deal at Indian tax-payers expense, the government is now aborting the tender process for 114 jets and returning to HAL.

Meanwhile, the foreign OEMs the government was trying to lure to invest in India, are bewildered by another googly delivered by India. If Rafale fighter jets are going to be procured then why make the song and dance over a new tender for 114 fighter jets? If this was a mistake, does this also not mean that cancelling the 2012 deal was wrong? To revert to Rafale now also means that domestically-produced content in them will be modest—far less than envisaged under the 2012 deal.

The long and short of it is that the Modi government is caught in a web of its own making. By constantly changing rules, procurement decisions and policy framework for the military, it has shown that after six years they are still low on the learning curve.

Indeginisation means promoting domestic technological and scientific advance and improving local manufacturing capability. Right now the latter capability stands reduced to making military goods in India even if the actual manufacturing skills and technologies are owned by foreign OEM. The sad dependence on foreign suppliers for key parts and components also remains intact. The ‘Make in India’ variety of indeginisation means that even if money to buy military hardware and systems is plentiful, India will remain hobbled by dependence on foreign owned-OEMs and foreign governments with their own axes to grind.

So money or no money, confusion persists over the direction of India’s military re-structuring and indeginisation, but militarisation for suppressing people at home carries on. Meanwhile, a slowing economy is hurting people bad.

The writer is a civil rights activist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.