The Selling of a Car and the Irrationality of Those Who Criticise It | Outside Edge

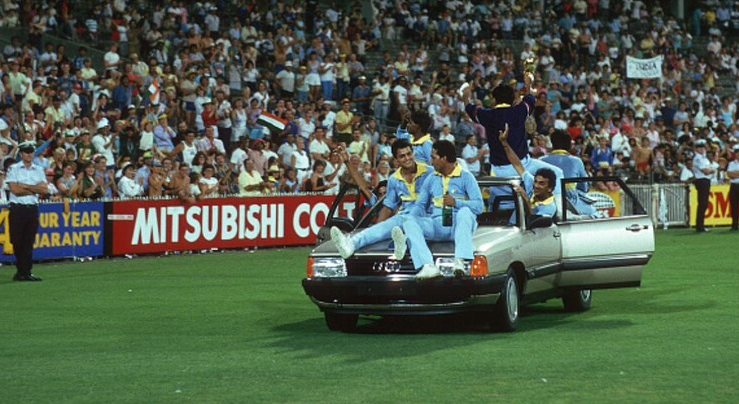

Indian cricket’s most famous car would not be Sachin Tendulkar’s Ferrari but the Audi 100 won by Ravi Shastri along with the Champion of Champions award at the World Championship of Cricket Down Under in 1985.

How difficult was it for the monk to sell his Ferrari? How did he reason with himself? The money from the car would help fund a trip to the Himalayas for a spiritual journey towards possible enlightenment. As if the hypnotic purr of a V12 or V8 was not serving that purpose. The deeply emotional, and even spiritual, connection we have with our automobile — be it a car or a bike — is tough to describe, and very difficult to sever. So, if one has to sell a Ferrari — the ultimate of cars — one either should be ready for austerity, monkhood perhaps, or has to be God.

Wonder how difficult it was for Sachin Tendulkar to sell his Ferrari then? The car — a 360 Modena — came with its own trappings and obligations. It was a gift from Michael Schumacher on behalf of Fiat. It was to commemorate the moment Tendulkar surpassed Sir Donald Bradman’s tally of centuries in Test cricket. Tendulkar, cricket’s all-endorsing embodiment of God, pulled it off with the kind of detachment only eclipsed by his detachment towards his duties as a Parliamentarian. The car had no emotional value once the pictures were taken.

Dutee Chand is neither God, nor a monk. It is no wonder she failed to sell her car, a BMW.

Among the most celebrated symbols of upward mobility in India — or any country for that matter — is the car. Owning one, arguably, has a larger bearing on status than, say, buying an apartment. It is not just about the commute. The owner negotiates [mostly] self-imposed class divisions holding its wheel. He or she announces the arrival, EMIs notwithstanding, much before making it actual.

There is a catch though. As much as buying a car in a consumerist world symbolises success, trying to sell one, no matter what the reasons may be, comes with it, weirdly enough, a stigma. Call it the counter-balancing act — the big dip — in the hyperbolic success curve you plotted while buying it in the first place. And, if the assumption was that such stigma is reserved for you and I, then think again. Chand, after all, may not be a sporting God, but she is not your daily office commuter either.

Also Read | Indian Football Should Encourage Merit But Also Provide Avenues to Judge It

She decided to sell her car last week. Chand may have had 100 different personal reasons to do so. It could well be that she needed the money for training. Or perhaps she just wanted to liquidate this depreciating asset which would soon have become a maintenance nightmare, hard to manage with her Group A level salary from the Odisha Mining Corporation. She could use that money for something more constructive, or even just put it in her bank account for rainy days — for times like those we are living in at the moment. There is no law in the country which requires you to reveal why you want to sell your car. Of course, the prospective buyer might want to know your motives, to ascertain the vehicle’s history and legality.

Chand’s reasons should have been hers alone. But, her being cash-strapped has somehow been construed into a narrative that hints at the collective failure of the country’s sports mechanism. The Odisha government — at whose behest Chand trains in her home state — took this as a personal slight. So did the Union sports ministry, which provides for her training and competitions abroad. Before the government departments got involved, Chand’s statements to the media, or in the social media post where she announced her intention to sell the 3 Series Beamer, went viral with the right kind of ingredients to add virulity. Coronavirus could learn a few tricks here, if needed.

Needless to say, the country — the social media representatives of India that is — were split right down the middle. Many former sportspersons pointed to the situation of an elite athlete as an indicator of how haphazard the system in place is. This despite knowing that careers of athletes who have made it into the national set-up are well taken care of compared to some of the other countries across the world — a list that includes the USA.

The social media storm and controversy around Dutee Chandâs BMW sale episode, a personal choice could be indicative of a larger malaise. It seems a slightly less caustic version of the larger threats posed on individual freedom.

Many others who are part of public and private sporting entities cited it as an attempt by Chand to reap some outward benefit from showing distress. As if to reiterate that, the state government listed out the cash, incentives and support doled out to the Asian Games silver medallist over the past five years. It was an attempt to clear their own position, even if it meant looking petty. A knee-jerk reaction to a social media debate that should not have taken place at all.

Details of financial support provided to an athlete set to represent the country should always be in the public domain. That is, however, easier said than done considering the layers through which the cash trickles down to its intended objective in the country. It is not perfect, for sure. And things only come out if one RTIs it or someone decides to sell a car.

Also Read | BCCI Ordered to Pay Rs 4,800 Crore to Deccan Chargers

Perhaps Chand was trying to pull off something here. Perhaps she was indeed trying to, like some put it, “milk the system”. However, the system in India is put in place with definite guidelines and some semblance of accountability. No one can “milk” it randomly. For instance, Chand is not part of the TOPS funding for elite athletes simply because she does not meet the criteria despite winning Asian Games medals. And, just to illustrate the integrity of the system and its objectivity, she would not meet that criteria simply by ridding herself of the burden of a BMW 3 series, one of the most expensive cars to maintain in India.

Chand never received the car as a gift. She bought the car using her own money, using part of her Rs. 3 crore award she received from the government for winning medals at the Asian Games. It was Chand’s way of announcing her arrival to the mainstream, much like many of the SUV flaunting elite wrestlers of the Indian team. Much like MC Mary Kom, who drives around New Delhi in a Mercedes SUV which costs close to Rs. 1 crore. A couple of years back, outside the World Championship venue in the capital’s Indira Gandhi Stadium Complex, Mary, while explaining some fancy add ons in her car, spoke about how the Gurgaon showroom from where she bought it, made a boxing ring outside and let her drive off it after the purchase. She was beaming when she said that. You could understand the symbolism of the moment, where she bought an expensive car and with it acquired the power to stick a finger to the world and its restrictions. The scope of a car indeed goes beyond the freedom of commute, and the adrenalin rush of driving it fast.

Talking about fast cars, Tendulkar, admittedly, loved big beasts. However, he chose to sell one of the fastest cars in the world. One he received as a gift. The stigma of sale caught up with God too. He was selling what is a prized possession, a trophy and recognition of his achievements with the bat. Something which commemorated not just his stature in cricket, but also that of the great Bradman, and F1 titan Schumacher, connecting all three together in a union rare in sport. Tendulkar, hardly flinched in the face of the criticism he received for deciding to sell the car. He went ahead anyway, helped to the hilt by the kind of immunity to criticism cricket stars get in the country.

Tendulkar was a brand ambassador for Fiat in 2002, the time he received the car. The Ferrari could perhaps have been pretty much part of the deal. And, Schumi and Tendulkar are hardly friends. They were in this act as smaller players in the larger game the brands orchestrated.

Tendulkar, however, tried to pull a fast one in the process. He tried to get the import duty for the car waived by the government. That is what real milking of the system is.The attempt was foiled by a PIL. That Fiat also came forward to foot the import duty of the car is proof of the larger deal in play. It indeed throws out the emotional attachment motorheads associate with automobiles. Tendulkar’s passions lay elsewhere, we all know.

Indian cricket’s most famous car would not be Tendulkar’s though. It would be the Audi 100 won by Ravi Shastri along with the Champion of Champions award at the World Championship of Cricket Down Under in 1985. It was not a gift, but a trophy earned on the field. And, rightfully, the import duty for that car was waived for Shastri. And, despite the differences one has on how he runs, or rather let the Indian cricket team be run by other powers in the set-up, one can only salute Shastri for holding onto that trophy from the highest point of his career. He still owns the car, hardly drives it though. It symbolises in many ways the forward movement of Indian cricket (and Shastri himself).

Also Read | Real Seal La Liga Title as Barcelona Capitulate Magnificently

That Audi is different, it used to occupy Mumbai roads differently too at the time: cricket’s first foray into the realms reserved for Bollywood superstars of that city. It was a trophy that doubled up as a status symbol and had the added allure of street cred. It was never going to be sold for petty cash. Tendulkar’s Ferrari was different. It symbolised the arrival of an Indian cricketer as alpha sports endorser. It’s sale was predetermined right from the time the keys were handed over to him. Chand’s BMW is different because it symbolises personal choice and nothing more. And it was also a choice that she tried to exercise while trying to sell it.

Of course, it has grown out of proportion now, into the realms of mudslinging, clarification and counter clarification while the original point gets missed — the big question. Since when did Indians lose their liberty to exercise personal choices provided it does not act as a threat to anybody’s life?

You and I know the answer to that question and the reasons behind this scenario’s prevalence in the country. Chand’s episode could be indicative of a larger malaise. It seems a slightly less caustic version of the larger threats posed on individual freedom — from the right to speak one's language of choice, eat the food one prefers, to the choice to pursue knowledge and practice a religion.

The Ferrari or BMW in the room is growing bigger by the day. We are not at liberty to exercise our choice to sell for we bought it with an EMI that runs till 2024 at the least, and the fineprint does not allow early closure.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.