Shanti Mullick: A Mystical Passer in a Physical World | Indian Women’s Football History Special Series

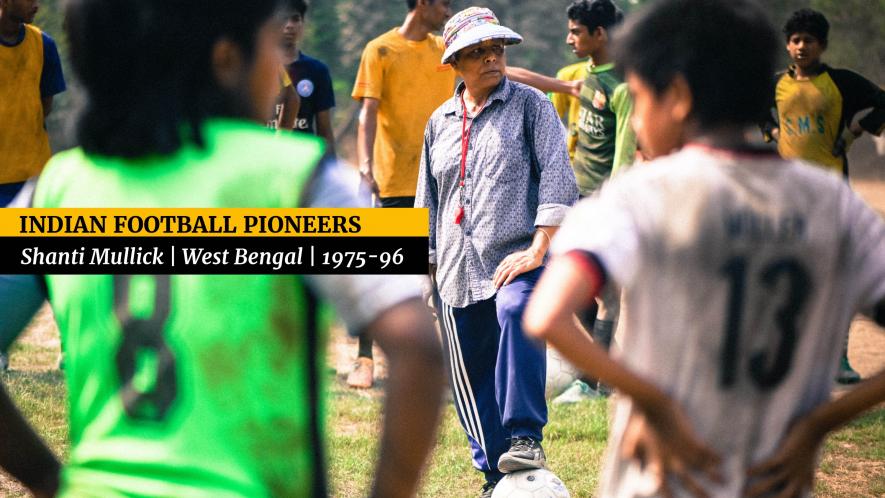

Former Indian women’s football team player Shanti Mullick (Pic: Vaibhav Raghunandan).

Pass. Few words mean so many different things. Doctors pass you fit for discharge. You could be passed up for promotion and pass judgement on those that get it. And that is only in English. Pass in Hindi means other things. It is a measure of distance. It is also a measure of possession.

A pass in football is where physics and the mystic combine. You can shoot, throw, chip, scoop, hit, hold and dribble a football. The fundamentals of these can be taught in a myriad of different ways, and a kid can learn them in a myriad of different ways. Players shoot differently, dribble differently, throw differently but the first thing they’re taught is to pass. There are no myriad ways to start with. It's called the push pass. Push tells you what to do. But such is the power of the pass that it becomes pushpass, the emphasis on the last syllable more than the first. You hold your ankle tight, tilt your foot so the toes point outward, and meet the ball with the inside metatarsal, cushioning this with the curve of your foot. You could pass the ball the same way for weeks on weeks before ever entering the mystic world of the pass. Make that one pass that turns into a noun. That pass.

But first you need to learn to pass. And on a dusty field on a winter morning at Rabindra Sarobar stadium in Kolkata, Shanti Mullick shows a group of kids how to do it. It’s a mock nine-a-side game, Mullick the referee (but actually the coach), pulling the play back to fix mistakes constantly. And this time she’s taken issue with a pass, one actually horribly misplaced, the purveyor receiving an earful. He’s gone to the mystic without understanding the physics. Trying to be Messi and succeeding, albeit not in the not the way envisioned. Mullick tells him exactly that, in Bengali. “Why are you trying to thread a needle the tough way, when there’s a simpler way to do it,” she screams, pushing him away and taking up his position, asking for the ball back. She tells everyone to reset, blows the whistle and then plays a simple pass out to the wing, where the receiver collects it and in the same motion passes the ball into the box. The striker taps in to score. “Why are you trying to pass to him through the bheed? There are more players on your team. Pass there outside, it will be sure shot goal. Pass to her. She is also playing.”

Also Read | Indian Goalkeeping: How the Bar is Getting Lowered, One Super Season at a Time

An hour later over boiled eggs, biscuits and hot tea (served from a flask she carried from home) she explains what went wrong. Mid monologue she is interrupted by a parent asking about the next week’s schedule. Mullick puts her cup of tea down and takes the mother aside to a corner of the room. The room is the administrative office of the South Kolkata referee association, sponsors and supporters of Mullick’s coaching centre. The training is free of cost, with city charities and the referee association picking up the tab for expenses of equipment, a stipend for the junior coaches and maintenance. They have six coaches, all of whom congregate around a large table set in the middle of the room, to serve themselves tea.

“She never stops talking about football. It’s actually a bit of a problem,” Anamika Sen says, half turning in her chair to scream at Mullick to come and get something to eat. A former footballer herself, Sen is one of a select few FIFA listed women referees from India — the second ever in fact — and coaches at the centre for free. “The main thing I’ve learnt about Shanti di is that she’ll do what she wants. You can try and make your case, but she’ll do what she wants.”

And, as a kid, Mullick wanted to do everything. Normal human beings play sport for pleasure. The few professionals put their slog on, and go on to represent states, provinces or employees. An elite group goes on to represent their countries in sport. Shanti Mullick, for the record, has represented India in football, hockey and sepaktakraw (“I was called to the cricket team, but I didn’t go… football was my love at that time”). She grew up playing many more, simply because the multi purpose sports facilities she accessed had athletes of all kinds around.

Also Read | Covid-19 Heartbreak: India out of AFC Women’s Asian Cup After Biosecure Bubble Breach

Inasmuch as it is admirable, it is reflective of the time itself. When Mullick was growing up, women’s sport was an afterthought with federations, associations and governments paying little to no attention at all. Those playing were renegades, recognised (barely), and often recognised and silenced immediately. Mullick captained the Indian team at the 1983 Asian Championships, won the Arjuna award in football (the first of two women to have won it ever) and then walked away from the sport she loved to go and play hockey. Shanti di will do what she wants.

If only it were all as simple as that. If only it was a matter of wanting and doing.

“In those days, we were paid five rupees a game,” Mullick says, physically back at the table, but mentally half in and half out in the sun. “The team’s performances were attracting a lot of attention. I asked the federation to raise the allowance to 20 rupees. Aarti Banerjee was heading the federation and she refused. They threatened to drop me from the team if I kept it up. Woh mujhe kaun hota hai nahi select karne wala (who is she to not select me)...”

The federation’s cavalier attitude towards developing the women’s game is reflected in the fact that Mullick, an Arjuna awardee in football, got a sports quota job with Eastern Railways when she shifted to hockey. This story is being written in 2022, the third year of Covid-19 — three decades from when Mullick shifted sports to secure a livelihood — and things remain much the same. If you are a girl, playing a team sport, it’s perhaps more prudent to play hockey. Not just because hockey is ‘our national sport’ (a misnomer if there was one) but because there are more jobs available there.

Also Read | Maria Rebello: She Played Football, Lest We Forget | Indian Women’s Football History Special Series

“It’s beautiful to say I don’t play for money, I play because I love playing,” she laughs. “But it’s also funny how that logic is only applied to sports, never to any other profession (she makes it a point to say kaam, because ‘training karna padta hai’). I’ve never heard a bank wala say I love banking, I don’t want money to do it.”

It is the inherent nature of human beings to oversimplify complex things. When Mullick makes the comparison, it sounds like a simpleton talking. But it is a profound statement, a way of expressing wonder at something that is unexplainable. Her words are a precaution too; if you want to play sport, love it, but here’s the warning, make sure you don’t love it so much to be taken for a ride.

Even before the AFC Women’s Asian Cup kicked off, Mullick chose to ignore it completely. This, despite the fact that India were competing at the event for the first time in 19 years! Her reasoning was simple and sound, not emotional but heartfelt. She didn’t see any point of watching a tournament that would do little to nothing to help women’s football in India. She didn’t see the point of watching a tournament that she had played, scored in, and even reached a final. Despite a two decade association with the national team, and a lifetime playing the sport, Mullick remains a renegade, working outside the system rather than in it. Her Arjuna award has been relegated to a margin of history titled trivia.

“When Mullick came back to the game, after a six year hiatus, it was the 1990s. The All India Football Federation (AIFF) had taken over the reins of women’s football in India and subsequently expunged all historical records of the women’s game in the country prior to 1992. Everything Mullick and her teammates had achieved was deemed non-existent. A new order was established. A new history too (a trend that has been kept up with time; new historical records suggest India only started playing football in 2014).

“How ridiculous is that, you only tell me?” Mullick says. “We reached the finals of the Asian Women’s Championship twice, challenged the top teams in the world at the time, and were rising. You disregard all that…” she leaves the sentence hanging, distracted instead by the girl who was on the wing who never received the pass, wringing her hands by the door, trying to catch a coach’s attention.

“Ki hocche, boloon?” The girl says her mother wants to have a word. Mullick calls them in, and offers the mother tea, the girl a stare and a slap on the back to correct her posture. Before the mother can say a word though Mullick has got her concerns covered. “She’s good, she has the skills, the desire and the game also, but she needs to work on her fitness. Ei fitness player hobe na.” Excuses about exams (‘she needs to pass’), the pressure of home, Covid-19 are offered, but brushed aside gently by the coach. Anamika smiles and gently whispers to the girl to try and come to the stadium 20 minutes early everyday. A pat on the back, a ruffle of the hair and everyone is sent away.

“Sometimes I wonder what the point of training these girls is,” Mullick says. “There are over 60 children in the centre, boys and girls mixed, playing together. Some of the girls have played states, nationals, but what next? There’s no incentive to play more. There’s no jobs. No games or tournaments either. Not everyone can play India, some need to play for work… what about them?”

Pat comes the reply, supplied by the other side of her own brain. “Every kid won’t become a player, but I want every kid to become a good human being.” Minutes later, Mullick packs the thermos, her shoes, picks up a helmet and is ready to leave and is offering lifts? “Deshapriya? No problem. I live in Kalighat. I can drop you. I will pass it.”

That word again. And the most tantalising thing about it: its multiple meanings. No sooner do you pass that you receive one. Time passes by too.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.